UT Professors: ‘Anti-Critical Race Theory’ Law Is Attempt to Avoid Historical Truth

By Eniola Longe

Reporting Texas

Yasmiyn Irizarry, an assistant professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, discusses the measures used to collect data on race and racial identity, during the PBS show, “Blackademics Television,” in 2015. Photo courtesy of Hakeem Adewumi

More than 15 minutes after their sociology of education class, several students waited to speak with professor Yasmiyn Irizarry in the hallway of Patton Hall on the University of Texas campus.

One white student was not waiting to ask a question, but to thank Irizarry for her experience in the class as the semester neared its end.

“In a space that is very privileged and very white, this is a breath of fresh air and has truly shifted my perspective on learning,” the student said.

Irizarry’s class had discussed the role of race and implicit bias — stereotypes we hold about groups of people outside of our own awareness — in American schooling. She’d told students that, as a 15-year-old high school student in New Jersey, she too had held an unconscious bias — white and Asian students were intelligent, while LatinX and Black students, like herself, were not. Students had nodded as she spoke.

The class didn’t specifically broach critical race theory — an academic theory that holds that racism is embedded in public policy — but Irizarry does use elements of CRT in her class. Teaching honestly about race in the U.S. is vitally important, she said.

That’s why Irizarry is disappointed with a new Texas law limiting how race is taught in public school classrooms.

“College shouldn’t be the first time students learn about their history or the way society is structured,” Irizarry said. “We do them a disservice when they’re not prepared to understand how the world works and how they can address the issues that we face.”

The law, House Bill 3979, went into effect in December 2021. The measure limits teaching about race, racism, sex and sexism in relation to American culture and history for K-12 schools but does not explicitly mention CRT.

During the last year, CRT has become a catch-all buzzword among some conservatives for discussion of racism in the classroom. Even though the Texas law doesn’t mention the theory, the measure has come to be known as the “anti-critical race theory” law.

In a series of interviews with UT professors in March and April, most said the law is an affront to the teaching of historical truth regarding racism. The professors also singled out comments made by one of the law’s staunchest supporters, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick — who has pledged to revoke tenure for professors who teach critical race theory — as extremely concerning and a threat to educational quality in the state.

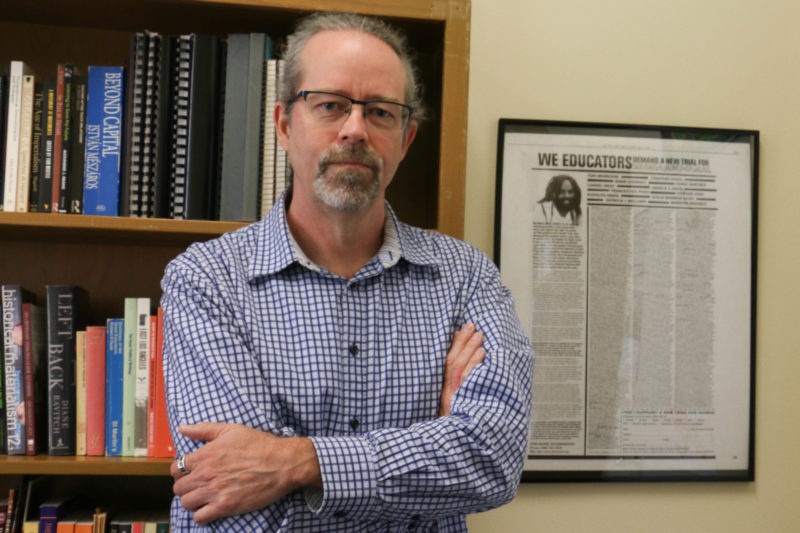

University of Texas at Austin professor Noah De Lissovoy, one of 175 university instructors who signed a declaration in response to a law limiting discussions about race in Texas’ classrooms, believes the new law will have a chilling effect on educators. Celeste Ramirez/Reporting Texas

So far in 2022, 175 Texas university instructors have signed a declaration in response to the law. Noah De Lissovoy and Angela Valenzuela, UT education professors, put the petition together.

“Professors are not going to just roll over on this; we recognize this as a real threat,” De Lissovoy told Reporting Texas.

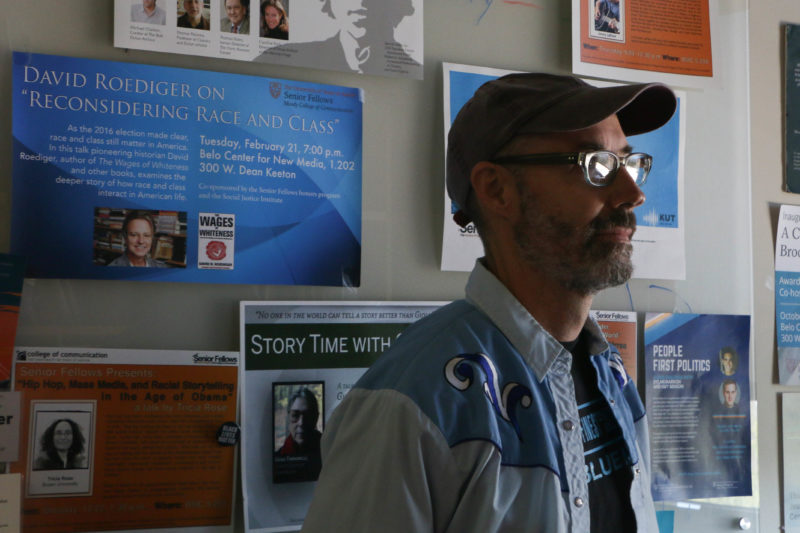

Dave Junker, a UT professor of public relations and the father of five biracial children, understands that it can be difficult for schools to teach about the country’s unfortunate racial past.

“It’s hard for white students, Black students, students of any race, ethnicity, cultural background, to learn and study about this,” Junker said. “There’s pain, there’s shame, there’s guilt, there’s anger, and there’s no way around those things.”

Dave Junker, a public relations professor at the University of Texas at Austin, thinks it’s important to teach U.S. students about this country’s racial past, despite the challenges of doing so. Celeste Ramirez/Reporting Texas

Despite the challenge, it’s critically important to honestly examine the way white people have treated Black people in the U.S., Junker said.

“The alternative this law suggests is to not teach it at all if you want to avoid those feelings or take a big risk in trying,” he said. “Responsible leaders should be doing their best to encourage the people who want to try this hard work.”

Sherry Sylvester, a research fellow with the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation, disagrees with the consensus among UT professors regarding teaching about our history of racism.

“(Students) should not be indoctrinated by a phony historical analysis that misstates the motivations of our nation’s founders and has been soundly rejected by virtually every serious historian in the country,” she told Reporting Texas.

Circe Sturm, a professor in the UT-Austin department of anthropology, doubts critics denouncing critical race theory understand it. While CRT is widely accepted by academics as a way to understand historical patterns of racism in the law, she said, it’s not taught in K-12 schools, and it’s sparingly taught at UT-Austin.

“Critical race theory has become the bogeyman; it’s cast this shadow over everything else related to the teaching of race and racism,” Sturm said. “You can’t reduce all theories of race and racism to CRT. They are using the term CRT, but in practice, when it’s applied, it’s being used to not allow people to teach about race and racism more broadly.”

Patrick’s embrace of a divisive culture war issue ahead of the election in November is simply playing politics, Junker said.

“It’s a result of an opportunistic politician who’s throwing red meat to the extremists and loyalists in the party, in order to mobilize them to go out to the polls,” he added. “Saying incendiary things gets you into the news cycle and he’s very good at that.”

Describing it as a kind of educational gag order, Sturm, Junker and De Lissovoy said Patrick’s comments could have a chilling effect on educators.

Classroom conversations are set to take the biggest hit, De Lissovoy said. Patrick’s consistent haranguing against critical race theory — and his comments about ending tenure at universities to combat CRT — are intended to intimidate educators from honestly discussing race and racism with students, he added.

“It’s really designed, in particular, to make people of color, students and professors, nervous and unwelcome,” De Lissovoy said. “It has to be seen as an expression of racism in itself, and must be condemned on those grounds.”

Sturm also expressed concern about Patrick’s declaration in February about banning the teaching of CRT in publicly funded colleges and universities. “I will not stand by and let looney Marxist UT professors poison the minds of young students with Critical Race Theory,” Patrick tweeted in February. “We banned it in publicly funded K-12 and we will ban it in publicly funded higher ed.”

If Patrick’s ban on critical race theory in colleges and universities happens, Sturm fears Texas students will have a hard time integrating into a modern world where sensitivity to cultural diversity is crucial.

“They’ll be less competitive on the job market for internships and entering the labor force, they are going to have a harder time understanding organizational culture,” she said. “There’s all these other impacts that happen when the state dictates what can or can’t be taught at the student’s expense.”

And despite the hand wringing over how racism is taught in the classroom, UT students are thoughtful about the topic in her classes, Sturm said.

“What I see is that students are actively engaged in these topics, they feel supported and free to work out their own positions and understanding,” Sturm said. “When students are provided with a broad set of educational materials, they have the capacity to make sense of them and find their own intellectual and ethical compass within them. No matter where they stand politically.”

The fact that historical inequalities are baked into public policy is something people still do not want to face, Junker said.

“The fact that we’re having completely crazy laws outlawing critical race theory, is a perfect example of why evading your own history is a bad idea,” Junker said. “For people to grow in a healthy way, and for the health of a democracy, it’s essential for us to know about each other. We have to be totally honest and clear eyed about our history.”