Texas’ Student Newspapers Feel the Pinch

By Cristela Jones

Reporting Texas

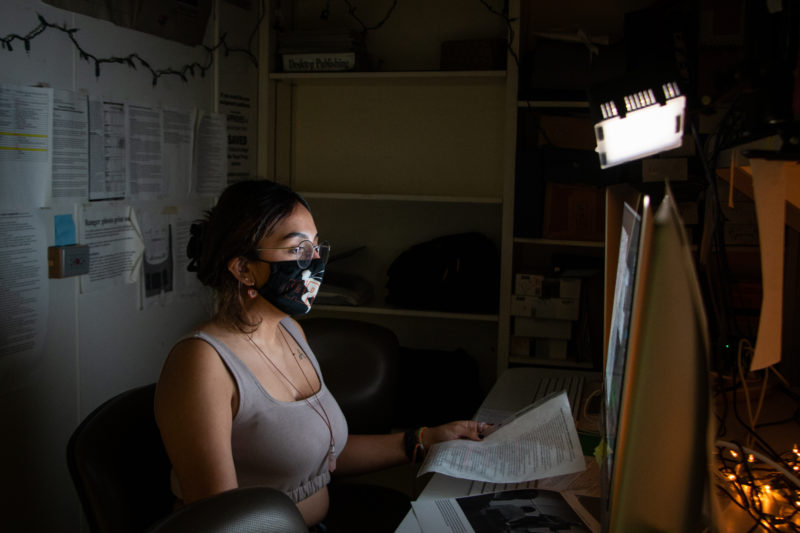

Veronica Alcorta, journalism sophomore and photographer at The Ranger, edits photos in the student newspaper’s darkroom at San Antonio College on Oct. 21, 2021. The 95-year-old paper announced Oct. 5 it would be closing its doors in December due to decreased funding, low enrollment in journalism classes and the retirement of journalism faculty. Cristela Jones/Reporting Texas

After nearly a century of operation, The Ranger, San Antonio College’s award-winning student newspaper, will cease operations in December due to decreased funding, low enrollment in journalism classes and the retirement of journalism faculty.

The Ranger is not alone. Other college newspapers in Texas are struggling for a variety of reasons, including decreased school funding, declining advertising revenue and COVID-19- related stresses.

Experts say the decline of student newspapers may have serious consequences — the lack of a popular training ground for future journalists and the loss of potentially powerful voices in holding college administrators to account.

The Ranger’s newsstands sit empty outside the student paper’s newsroom at San Antonio College on Oct. 21, 2021. Cristela Jones/Reporting Texas

Student newspaper operating expenses typically come from two sources — advertising revenue and school subsidies. During the past two decades, both sources have declined significantly. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated those trends, creating more staffing shortages and stress for student journalists working at college newspapers.

During the 2015-16 school year, San Antonio College provided $59,000 to The Ranger. That number declined to $7,000 in 2021-22, according to financial data from Mandy Derfler, academic unit assistant at San Antonio College. The Ranger ceased print publication and went online only in 2019 because of the cuts.

“You have fewer students coming in, and then the administration of the colleges looks at that and they go, ‘OK, you’re not taking in enough students,’ or, ‘You’re not producing enough graduates. We’re going to take funding away from you,’” Sergio Medina, editor of The Ranger said. “It’s like a snowball effect that slowly cripples the system.”

San Antonio College President Robert Vela told Reporting Texas that The Ranger is pausing operation due to “enrollment declines and budget reductions.”

“We have no intention of closing the paper or ending the journalism program,” Vela said. “A pause in publishing will be an opportunity to revamp, revisit and reimagine SAC’s journalism offerings.”

The Ranger’s Managing Editor Rocky Garza, left, and Editor Sergio Medina, right, stand in front of a wall of awards won by the San Antonio College student newspaper on Oct. 21, 2021. Garza and Medina were the only two editors on staff at The Ranger during the 2020-2021 school year. Cristela Jones/Reporting Texas

Robert Muilenburg is a professor of journalism at Del Mar College, a community college in Corpus Christi, and executive director of the Texas Intercollegiate Press Association. Community colleges are increasingly cutting funding for student newspapers and journalism programs, he said.

“A lot of two-year college administrations are looking at the two-year (journalism) programs as expendable, because they are more focused on trying to be certificate and diploma factories as opposed to giving students a very rounded and very thoughtful education,” Muilenburg said.

While many student-run newspapers at community colleges operate as part of journalism programs, most student newspapers at four-year institutions operate independently from journalism departments. Newspapers at four-year colleges are also seeing their budgets cut.

The student-run newspaper at the University of North Texas in Denton, The North Texas Daily, gets most of its funding from the university via student service fees.

In 2018, school officials sent a letter to the paper stating that over the next three years, the Student Service Fee Advisory Committee would “wean” its student media outlets off such funding.

Despite the decreased funding, the North Texas paper is still able to pay some staff members, said Kiara St. Clair, editor-in-chief of the paper. The majority of the paper’s staff, though, is unpaid, and only a few editors and senior reporters are paid $8.50 an hour.

Before 2019, Texas A&M University funded two professional full-time staff positions to help students run The Battalion, the university’s student newspaper. In 2019, the university eliminated one of the positions.

The move disappointed Brady Stone, 2020-21 editor-in-chief of The Battalion. The university should show it values journalism by “helping to make the journalism pipeline more robust by putting more money into the program,” Stone said.

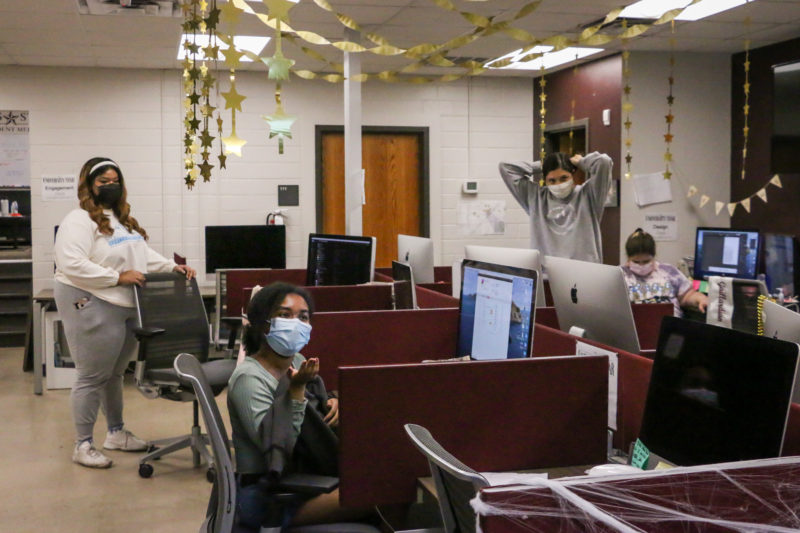

The University Star’s editorial team listen to editor-in-chief Brianna Benitez as they discuss their plans for the newspaper’s production day at Texas State University on Nov. 1, 2021, in San Marcos. The Star’s editorial team is an all-female team of students. Cristela Jones/Reporting Texas

During the COVID-19 pandemic, which has stretched over three academic years, The Battalion and The University Star, Texas State University’s student-run newspaper in San Marcos, reported additional declines in school-provided funding and print advertising.

COVID also took a toll on the mental health of reporters and editors, prompting some to leave their papers for other opportunities.

Before the pandemic, The Battalion had 60 to 85 people on staff, Stone said. By the end of summer 2020, that number was 30.

The University Star’s Editor-in-Chief Brianna Benitez, left, and Opinion Editor Hannah Thompson edit the student newspaper during production day at Texas State University on Nov. 1, 2021, in San Marcos. Cristela Jones/Reporting Texas

Brianna Benitez, editor-in-chief of The University Star, said the paper lost a dozen reporters and editors since the pandemic started. Prior to the pandemic, close to 100 students worked at the paper.

“When COVID first happened, everybody wanted to join, but as the year went on, people started to leave because it was just too much to handle on top of going to school, working and then dealing with the effects of the pandemic on their own personal lives,” Benitez said.

Benitez lost editors and reporters to better-paid internship opportunities and jobs. The staffing shortages prompted her to work as her own managing editor and sports editor.

“The work that we do is the work of a real-life newspaper, but we don’t have as many resources, and we don’t have as much funding. And on top of that, we go to school,” Benitez said.

Brianna Benitez, editor-in-chief of The University Star, works in her office at Texas State University’s student-run newspaper Monday, Nov. 1, 2021, in San Marcos. The University Star lost a dozen reporters and editors to better paid internships and jobs since she began as editor-in-chief in spring 2020. Cristela Jones/Reporting Texas

The decline of student newspapers means not only the loss of a fertile training ground for journalists, but also an important voice in holding college administrators to account, Muilenburg said. It’s one reason college administrators sometimes don’t support independent student media.

“College administrations see an engaged, active student media as more of a difficulty than a benefit,” Muilenburg added.

Barbara Allen, director of college programing for the Poynter Institute, a journalism think tank, said student newsrooms are the “greatest proving grounds in the world” for student journalists. “There is something shiny and vibrant and shimmering about the energy in a newsroom,” she said.

Allen said she “started the pandemic concerned about the business models of student media” and is ending it “worried about the students.”

“I am personally worried about the mental health of students, especially those involved in student media who feel compelled to inform their communities,” Allen said. “It’s a big emotional burden to take on as a 20-year-old, a 21-year-old.”

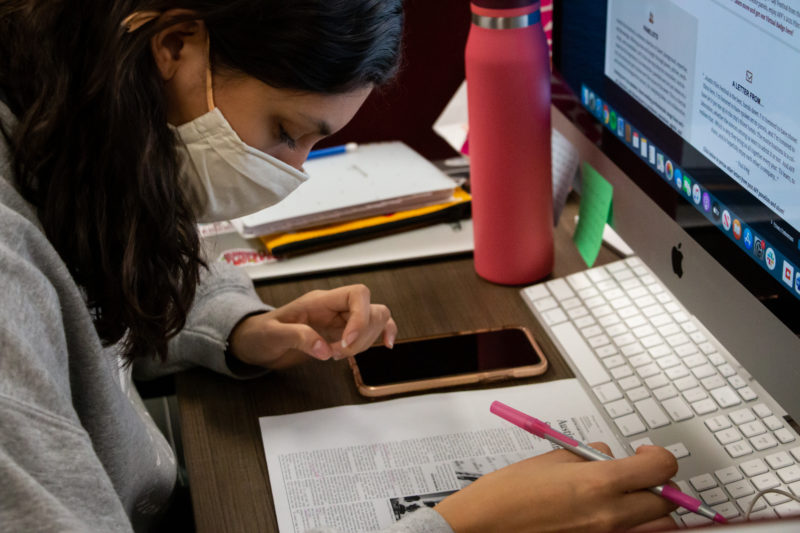

Sarah Hernandez, life and arts editor of The University Star, edits a draft of the Texas State University student newspaper on Monday, Nov. 1, 2021, in San Marcos. Cristela Jones/Reporting Texas

Rachel Royster, news editor of The Baylor Lariat, said working virtually during the pandemic took a toll on the community aspect of student media.

“It really felt like there was no team, and there was no staff. It was just me doing me, and every once in a while, this random name would pop on my screen to send back my story with edits,” Royster said.

Royster has worked to reassure her reporters that “they’re doing a good job” despite feeling overwhelmed and burned out, she said. The loss of student newspapers such as The Ranger should be alarming, she added.

“There’s always going to be a need for information. There’s always going to be a need for the truth, and we [as students] are the ones who get to decide that first,” Royster said.