Texas’ Famed Bigtooth Maple Trees Are Being Loved to Death by Deer

By Paula Levihn-Coon

Reporting Texas

Bigtooth maple trees, which turn bright colors each fall, are touched by the dawn light at Lost Maples State Natural Area in Vanderpool, Texas, on Nov. 12, 2021. Paula Levihn-Coon/Reporting Texas

VANDERPOOL — As daylight hours shorten each fall in the Texas Hill Country, the leaves of bigtooth maples transition from green to bright yellow, orange and red. The brighter the leaves become, the more visitors flock to Lost Maples State Natural Area to witness nature’s cheerful display, a rarity in a state dominated by oak trees whose fall colors are restricted to muted golds and browns.

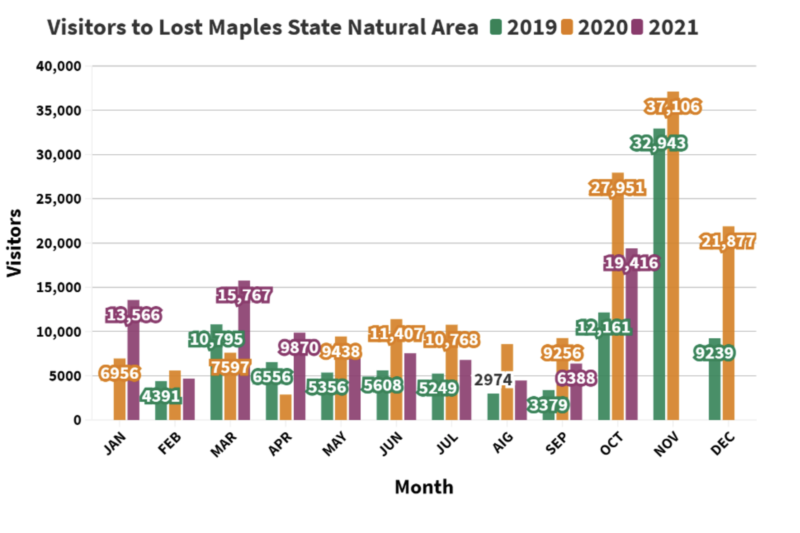

Since the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department opened Lost Maples to the public in 1979, thousands of people have enjoyed its colorful beauty. It has been particularly well-visited during the pandemic, with attendance reaching record highs.

“State parks were the only thing open, and people felt safe being outside, so we got hit hard,” said Lisa Fitzsimmons, Lost Maples’ superintendent. “We had less staff (with employees sick with COVID-19), same budget, same resources, yet double or more visitation. Despite the state opening up, we are still being slammed with visitors.”

Data is through Oct. 28, 2021. January 2019: new software was implemented, and records were not kept. March 2020: park closed due to COVID-19. April 2020: park closed until April 20 due to COVID-19. February 2021: park closed.

The maples are “bigtooth” because of the shape of their leaves and “lost” because they’re a relic of maple forests that thrived in Texas during the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago. When the ice retreated, only pockets of these trees persisted in Central and West Texas in cool, wet canyons.

Bigtooth maples display their colors in the Lost Maples State Natural Area on Nov. 12, 2021. Paula Levihn-Coon/Reporting Texas

Recently, however, scientists have collected data indicating that the future of these trees and the pleasure many take from their color palette could be at risk. An overabundance of white-tailed deer has been killing young trees by browsing on them.

“The adults have to be replaced at some time before they’re going to die. If you don’t have any new individuals entering the population, you’re not going to have any adults in the future,” said Oscar “Bill” Van Auken, professor emeritus at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

About an hour’s drive east of Lost Maples is the 3,814-acre Albert and Bessie Kronkosky State Natural Area, which the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department acquired in 2011 but is not yet open to the public. There may be more bigtooth maples on the ABK land than at Lost Maples, according to a study published in 2016.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s park superintendent, James Rice, left, and Oscar “Bill” Van Auken, professor emeritus at the University of Texas at San Antonio, take a break from touring the Albert and Bessie Kronkosky State Natural Area on Nov. 11, 2021. Van Auken has published multiple studies about the bigtooth maples. Reporting Texas Photo/Paula Levihn-Coon

By determining the age of dead trees in and near Tin Cup Canyon in ABK, one of many deep, sheltered limestone canyons that bigtooth maples prefer, Van Auken found that the largest numbers of bigtooth seedlings germinated between 1894 and 1988, with a peak in 1941. Since then, the population of young trees has declined, not surviving into adulthood as they did over the last few centuries.

In 2016, to determine where in Tin Cup Canyon bigtooth maples were located, Van Auken collaborated with a drone pilot to take aerial photos in the fall when bright-colored maples were easy to spot. He then used the data to determine that there were 3,002 adult and 671 juvenile trees in the canyon.

A juvenile bigtooth maple is protected by a cage in the Albert and Bessie Kronkosky State Natural Area. It is flagged with surveyor’s tape so researchers can find it to monitor its survival rate, which is estimated to be about 80%. Paula Levihn-Coon/Reporting Texas

To confirm his hunch that deer are eating baby maples, Van Auken caged young maple trees next to uncaged ones and compared their survival rates. The caged ones so far have an 80% survival compared with 40% for the uncaged trees, according to Van Aucken’s study.

Over the past hundred years, the number of deer in Texas has exploded because the predators that ate them have been killed or hunted.

Although bears and mountain lions were once common on the Edwards Plateau, they are now only occasionally sighted. Grey wolves and the occasional jaguars that roamed this part of Texas have been extirpated.

After unregulated hunting decimated the white-tailed deer in the early 1900s, the Texas Legislature passed laws protecting them and tasked TPWD with enforcing the regulations.

Since then, the white-tailed deer population in Texas has exploded. It is currently estimated to be about 5.4 million, with about 2 million on the Edwards Plateau of the Texas Hill Country, according to TPWD.

In October, the department issued a press release titled “Biologists Predict an Exceptional 2021-22 General White-Tailed Deer Season.” High fawn survival rates indicate an “overall robust population increase” headed into the upcoming deer hunting season.

Van Auken’s studies suggest that this will not be a good year for young bigtooth maple trees.

TPWD says it intends to take Van Auken’s findings into account with the goal of managing the white-tailed deer population to help young bigtooth maples survive into adulthood.

That effort has yet to begin, but James Rice, the parks department’s superintendent at ABK, is on board. “I have asked Dr. Van Auken to summarize the various papers and research into a simple findings report that we can use to begin to develop a Maple Management Plan.”

The plan, however, is years away as naturalists continue to survey the Kronkosky land to establish a baseline inventory of plants and animals.

“To develop a management plan. you have to know the site,” Rice said. “We’re still in this discovery phase when you get knowledgeable people like Dr. Van Auken to walk around and discover what is here.”

“What’s jumping out to us about this property is vegetative diversity. Everything starts with plants,” Rice said. “If we can manage this place to have continued vegetative diversity, then everything within it will fall in place.”

Losing bigtooth maples reduces this biodiversity. “The species that depend on it as a source of food would have to change or be gone,” Van Auken said. “The forest structure would change for sure.”

Severo Medrano, left, and his wife, Patricia, hike on the East Trail at Lost Maples State Natural Area on Nov. 12, 2021. These maples, a relic from the Ice Age, grow in steep, moist canyons which can make them hard to access for scientists who are studying them. Paula Levihn-Coon/Reporting Texas

But no one knows exactly what these changes might be.

Deer populations can be controlled by increased hunting, by increased predation or by fencing them out.

Unlike Lost Maples, which is largely unfenced, ABK has a high game fence around it that was installed in the 1990s by the Kronkoskys, who donated their land to the park. However, about 200 feet of it is missing and, as yet funds have not been allocated to repair it and Rice does not know if or when that will happen.

Bobcats and coyotes eat deer on the Kronkosky land, and Rice loves to spot them with game cameras. “The coyote out here is our friend because they’re a predator. When we see bobcats, we’re not surprised. It’s cool.”

But ever-diminishing amounts of unpopulated land is a threat to both predators.

In several years, when ABK will be open to the public, Rice fears the coyote will “be the first to go.”

Eleanor Brogie, left, her sister, Hazel, and dog camp with their family at Lost Maples State Natural Area in November. Scientists are studying the maples in hopes of protecting them for future generations. Paula Levihn-Coon/Reporting Texas

It will take decades to see how people, predators and bigtooth maples interact.

The bigtooth maples outlasted the Ice Age. With the help of scientists and volunteers working with government agencies, future generations of Texans may be able to enjoy their stunning fall display.