Seeing Black Churches of East Austin Through a New Lens

By Yelitza Mandujano

Reporting Texas

East Austin is forging ahead with new condos, restaurants and people looking to find their piece of the neighborhood’s quirky coolness. But one photographer is showing how part of old East Austin is struggling to figure into the neighborhood’s evolving identity.

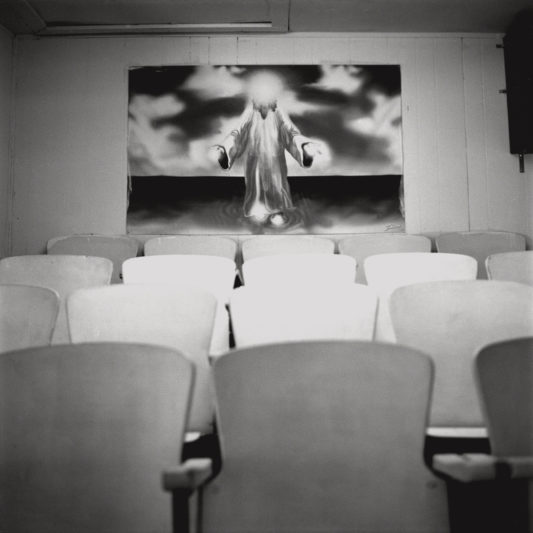

Wear and tear from decades of worship shows in the wood-slatted churches in Liz Moskowitz’s work, featured in a recent exhibition at Six Square, a nonprofit focused on East Austin’s black culture. The exhibit, the culmination of six years’ work, featured over a dozen churches that are mainstays in the area’s black community.

Six Square Executive Director Nefertiti Jackmon says Moskowitz’s photos reflect her organization’s mission.

“[I]t’s letting people see [gentrification] in a new way,” Jackmon said in an interview.

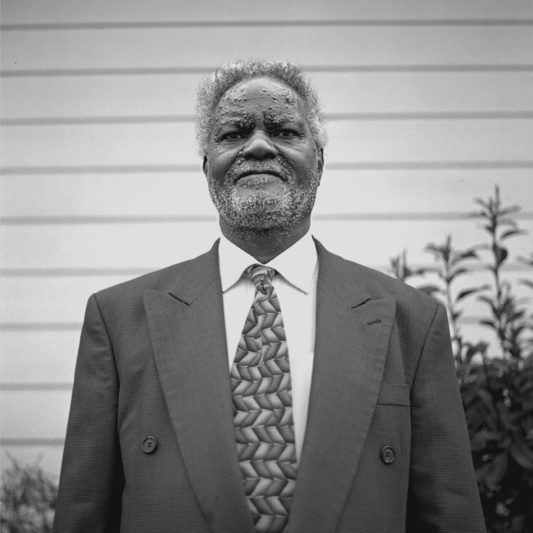

Black-and-white portraits of congregants of various ages dressed in their Sunday best, posed in front of worn-out church buildings, is a theme throughout Moskowitz’s photographs. She says she used a film camera because it gave the images a timeless look. Her work provides a glimpse of what came before while celebrating today’s black-church communities.

Moskowitz’s idea for the project came from bike rides through the neighborhood.

Liz Moskowitz. Emree Weaver/Reporting Texas

“I grew up in Brooklyn, which is heavily gentrified. … I saw many similar patterns in East Austin,” Moskowitz said in an interview at her home in East Austin. “I started attending different churches and documenting them with the members.”

Moskowitz’s photographs reflect the precarious situation many churches are in, with some shuttering their doors and others trying to hold on as members age or move out of town.

Historically, Eastside residents have been majority African-American and Latino, but that is changing as rents and property values rise. Today East Austin is 55 percent Latino, 16 percent African-American, 24 percent white and less than 1 percent Asian, according to the website City Data, which processes user-generated information — census data do not pinpoint neighborhood demographics. Citywide, Austin’s African-American population has dropped more than 5 percent since 2000, according to census data, while the Latino population has increased 5 percent and the white population, 3 percent.

One of Moskowitz’s subjects, the United Friendship Baptist Church, abruptly closed its doors in 2015, to the surprise of its members and the church director. The stepmother of Church Director Frieda Sauls sold the property to a California-based investment group for $1.2 million last July, according to records from the Travis Central Appraisal District.

In a Moskowitz portrait, the morose expression on Sauls’ face as she stands next to her father and stepmother in front of her church’s aged wooden doors underscores the poignancy of the neighborhood’s demographic changes.

Another church, which Moskowitz didn’t photograph but is losing members, is 152-year-old Wesley United Methodist Church. Terrell Edison, a local disc jockey and 17-year member of the church, says he and his wife drive 30 minutes from Hutto every Sunday for worship.

“I’d say about 60 percent of the congregation now commutes to our church,” Edison said after service on a recent Sunday.

In 2016, Moskowitz, a University of Texas at Austin graduate, received a $3,000 grant from the Dallas Museum of Art to fund her black-churches project. The cash helped her to continue documenting a community that is less visible in a rapidly growing city.

“I’m witnessing the physical and cultural landscape changing,” Moskowitz said. “Part of this project is meant to capture that and hopefully help others get a better understanding of it.”

Part of that change comes from rising property values. In East Austin, the average value tripled between 2011 and 2014, according to the real estate website Realtor.com. Median household income also jumped to $350,000 from $125,000 during the same period.

Moskowitz photographed Springdale Church of God in Christ’s worn, wooden sign with faded, hand-painted lettering. The church sold its property in 2016 after its value rose by almost 650 percent in the preceding four years, according to the county appraisal district.

While there are no hard figures, locals have a general sense that church community is struggling.

“I don’t know how many churches have closed down, but I do know of about six that have relocated,” said Rev. Sylvester E. Chase Jr. of Wesley United in a telephone interview. “I don’t know of any new churches that have opened recently here, and I doubt there is.” Austin Mayor Steve Adler, who attended a recent Sunday service celebrating Wesley’s 152nd anniversary, says the cost of housing is making living in East Austin untenable for some people.

“Housing costs are increasing four times faster than income,” Adler said in an interview. “That’s causing an affordable-housing shortage,”

The lack of young churchgoers is another threat. Wesley United is taking a proactive approach to reach young people.

“More than half of millennials are unchurched,” said Leonard Woods, a lawyer and member of Wesley United’s Intergenerational Choir. “It is our job to reach out and help them.”

Six Square’s Jackmon said her focus is on the neighborhood’s future, despite the dire message some could draw from Moskowitz’s photos.

“We are not trying to preserve black culture in East Austin — preserve means it’s dead. We’re trying to keep it alive because it’s still very much alive,” she said.