Racial Politics and Economic Woes Roil an East Texas City

By Vicky Camarillo

Reporting Texas

A sign with the slogan “Paradise in the Pines” welcomes visitors to Crockett, Texas, which lies 110 miles north of Houston. Vicky Camarillo/Reporting Texas

Darrell Jones knew right away that something was off about the letter.

It was August 2018, and Jones, a City Council member in the East Texas town of Crockett, had just retrieved his mail. The return address belonged to a friend, a local civil rights activist, but his friend’s name wasn’t on the envelope.

Jones, who is black and was born and raised in Crockett, had developed a reputation for being outspoken when it came to issues of race. A few days earlier, during a packed City Council meeting, he’d called Crockett’s mayor, a white woman named Joni Clonts, “a racist,” according to meeting minutes.

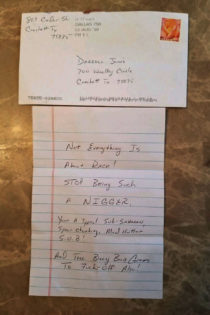

He suspected the letter was bogus but opened it anyway. Scrawled on the page was the following:

“Not Everything Is About Race! STOP Being Such A N—–. Your [sic] A Typical Sub-Saharan, Spear Chunking, Mud Hutter S.O.B.!” The letter was postmarked Aug. 1, two days after the council meeting.

Jones took the letter to the police. They ruled out Jones’ friend as the sender but couldn’t figure out who sent it. They told him: If you get another letter like this, don’t open it. Bring it straight to us.

“It didn’t faze me,” Jones said. “I just think I touched a nerve because I speak up for what’s right, and I never will stop.”

Racial slurs and expletives appear in an anonymous letter sent to Crockett City Council member Darrell Jones. The letter arrived shortly after a contentious City Council meeting where residents argued to abolish the city’s economic development corporation. Photo from the Facebook group, For the Love of Crockett, Texas

In this case, that meant defending the Crockett Economic and Industrial Development Corporation and its black executive director against Clonts’ effort to abolish it. Because of poor leadership, according to Clonts, the corporation was not fulfilling its mission of attracting businesses to the economically struggling city. Opportunities for work had been slow to grow in this city of 6,500, where employment rates did not surpass 50% between 2009 and 2017, according to Census Bureau data, and where the population has dwindled since 1990.

With a per capita annual income of less than $16,000, Crockett ranked among the 20 poorest cities in the country in 2018, according to a report by 24/7 Wall St., a financial news website. And the situation has been even more dire for Crockett’s black citizens, who make up about 45% of the city’s population (non-Latino white people make up about 34%, and Latinos of any race make up about 17%). Over the past decade, the unemployment rate among black residents has been, on average, at least three times that of white residents.

In October 2016, City Council had named James Gentry executive director of the economic development corporation. Gentry, in his late 50s at the time, was the first black person to hold the post, and many black residents, including Jones, said Clonts simply couldn’t abide a black person being in charge. It’s an accusation she adamantly denied. “They’re just trying to grasp at anything, so they just use the race card,” Clonts said at her restaurant, the Moosehead Café, in January.

The fight over the future of the corporation raged for almost a year. Many black residents said the effort to abolish the corporation was an example of racist white city leaders and residents feeling empowered amid the rise of a president who exploits racial division for political gain. Clonts and many of Crockett’s white residents insisted race wasn’t a factor. On both sides of the issue were a handful of people, both black and white, who simply wanted the discord to end and held a series of prayer circles on the town square to that end.

But then, in May, something surprising happened. Residents voted to save the corporation. They also voted Clonts out of office and elected Ianthia Fisher, the first black woman to hold the post. (Two black men had previously served as mayors of Crockett, though neither was elected; they were both appointed to fill unexpired terms.)

Ianthia Fisher, right, joins Crockett, Texas, residents on Aug. 20, 2018, for the Prayer on the Square, a monthly prayer circle created to heal the racial divide in the city. Fisher was elected mayor in May 2019. Photo courtesy Megan Whitworth

Some of the civic rancor subsided in the months after the ground-breaking election. But many white and black people still have opposing views of the role race played in the fight over the economic development corporation. Whether the election represents a turning point for race relations in Crockett remains an open question. But one thing is clear: The situation in this East Texas town is an example of how racial politics and economic struggles collide in the age of Donald Trump.

***

James Gentry got the bad news on July 1, 2018, when the mailman arrived with his daily batch of letters.

James, you need to see today’s paper, the mailman told him, referring to the Messenger, the newspaper of neighboring Grapeland. They’re coming after you. When Gentry’s wife brought home a copy of the paper, there it was: Crockett City Council member Butch Calvert, an ex officio member to the economic development corporation board, had written a letter to the editor calling for the termination of the CEIDC.

The relationship between the CEIDC and the council had been plagued by “miscommunication, distrust and blatant insubordination,” wrote Calvert, who is white, and the high turnover and apathy of the board prevented it from being an “effective governing body.”

Gentry felt blindsided. “Butch did talk to me, but he didn’t tell me he was going to take it to that level,” Gentry told Reporting Texas.

Calvert had told him about his concerns with the corporation in a one-on-one meeting in June, Gentry said. He’d suggested abolishing the corporation, selling its property to pay off its debts of almost $3 million and using the portion of sales tax revenue that was earmarked for economic development, about $500,000 a year, to improve the city’s pothole-ridden streets — which many residents say make the city a hard sell for new businesses. The responsibility for economic development would fall to the City Council, Calvert told Gentry.

But Gentry refused, arguing that the corporation was important to Crockett’s economic future, and that $500,000 wasn’t nearly enough to repair the city’s shoddy streets. Gentry thought that would be the end of it; he said he had no idea Calvert would go public with his plan.

The trouble had started in late 2016. The previous executive director of the CEIDC, Flint Brent, and his assistant abruptly resigned that October, and the board promoted Gentry from board member to executive director. Gentry, formerly a drilling engineer, worked on a volunteer basis until he was officially appointed to the position in December. His starting salary was $77,200 out of a $1.3 million budget.

In January 2017, the City Council, incensed that the corporation board had granted Brent and his assistant $27,000 in severance without the council’s approval, replaced all the board members. Although Gentry had also voted for the severance pay, the council did not have the power to fire him; that was up to the board. Gentry was spared.

Municipal elections in May 2017 brought a shake-up in city leadership. Calvert, a stay-at-home dad, won a seat on the City Council, and Clonts was elected mayor. Clonts had served as the chair of the Houston County Republican Party for more than a decade and owned Crockett’s popular Moosehead Café — a restaurant where campaign signs for Trump and GOP politicians plaster the walls.

A sign displayed at the Moosehead Café in April 2019 urges voters to terminate the city’s economic development corporation in the May election. The restaurant is owned by Joni Clonts, the former mayor who was voted out of office in the same election. Vicky Camarillo/Reporting Texas

Soon after joining the council, Calvert tried working with the CEIDC board, determined to heal the divide between the board and the City Council. But he didn’t like what he found.

Calvert said board members regularly showed up unprepared for meetings and waffled on decisions, thus losing deals and costing the city potentially dozens of new jobs. Members routinely resigned and had to be replaced; Calvert estimated that a dozen new members have been appointed to the board’s five seats since mid-2017.

“You can’t really be effective as a board if you’re in a constant state of upheaval,” Calvert told Reporting Texas. “That’s where I really became frustrated and disillusioned with the economic development board.” Calvert said he couldn’t disclose more details about the board’s failures because they involved confidential discussions among board members.

But there were other losses that got media attention and added to public despair, such as the closures of a state school and a juvenile detention center. Failed projects left the CEIDC without any income to offset incentives made to attract the employers, and Clonts claimed that the corporation had been careless in giving the incentives.

Gentry insisted that the corporation had done some good for the city. In an interview with Reporting Texas, Gentry touted ElastoTech, a rubber molding manufacturer that employs about 20 people, as a success story for the CEIDC. He’d helped establish that business in Crockett during his time as board president — though that was in 2000, almost two decades ago. He also pointed to the corporation’s investments in existing local businesses, such as a veterinary hospital and a clothing store.

Gentry said in an interview that some board members were not as dedicated to the CEIDC’s mission as he would have liked, but by early 2019, those members had been replaced and the corporation was back on track, he said.

Ultimately, Calvert believed the corporation alone was not to blame for the town’s economic woes. But he felt the city would be better off improving its infrastructure to attract new jobs than continuing to allot funds to the corporation. The day after his unsuccessful meeting with Gentry, he wrote the letter to the editor of the Messenger calling for the termination of the CEIDC.

***

Clonts said she read Calvert’s letter and agreed with it. She had long viewed the corporation as a “waste” of taxpayer money, and it was time to take the matter into her own hands.

She drafted a petition calling for the CEIDC to be abolished. She went door to door soliciting support and asked patrons at her restaurant for signatures.

Word of the petition spread through the small town, sparking a backlash from some black residents. City Council member Marquita Beasley, one of three black members of the five-person panel, addressed black residents’ anger during a meeting on July 30, 2018. If you want growth in Crockett, she asked, why would you disband the economic development corporation? “And then, on top of that, the director is black,” Beasley added, according to the Houston County Courier. “And that’s why all the black people felt like it was attacking him.”

By August 2018, Clonts had enough signatures to pass her petition to the city secretary. At its meeting on Aug. 13, 2018, the City Council was scheduled to call the election to terminate the economic development corporation. But, during the meeting, council member Ernest Jackson objected, saying the city charter contained “no provision for an initiative, referendum or for a recall.”

“This council cannot accept it because we are working outside of the municipal constitution that was already in place,” he said, according to the meeting minutes. “It is incumbent upon us to follow law and not the whims of citizens.”

But state law trumps local ordinances, Calvert said, and state law dictated that the city call an election if 10% of registered voters signed the petition. “If we do not pass this resolution, then we are in violation of the laws of the state of Texas,” Calvert said. “We will get sued.”

Calvert made a motion to approve the resolution calling for an election. There was no second. The motion failed.

The next day, Calvert sued the city.

On Sept. 21, Calvert and the city agreed to a settlement setting the election for May 2019.

Calvert said he was happy that voters would get to determine the fate of the CEIDC.

Clonts told Reporting Texas that she was confident voters would send Gentry and the corporation packing.

“I think if people really realize what the plan is or what really has to be done to help Crockett, they’ll vote to terminate,” Clonts said.

***

On a Monday night in January, a smattering of cars drove past the Houston County courthouse, a stately Art Deco structure that anchors Crockett’s sleepy town square. Around the courthouse stood a bank, an insurance office and several mom-and-pop shops, along with a handful of empty storefronts. And the Moosehead Café.

Despite the biting cold and the darkness, 11 residents gathered on the front steps of the courthouse. For about 10 minutes they prayed, out loud, all at once — for the health of their loved ones, for economic prosperity and, mostly, for peace in their city. The voice of one man, the Rev. Arvin Medlock Jr., rose above the others. Though he’d donned sweat pants, a hoodie and a beanie for the night, his voice soared as if he were addressing the congregants of Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, where he is a pastor.

“Intervene in this city right now, God,” Medlock said. “We want this city to be a city of love. We’re praying against the racial divide. We can’t do this on our own.”

This was Prayer on the Square, a monthly gathering created by two women: LaCree Beasley, who is black (and is councilwoman Marquita Beasley’s sister), and Ashley Bankhead, who is white. The first edition, held on Aug. 20, 2018, saw scores of participants — black, white, Latino — who joined hands and stayed rooted to the spot despite a downpour. Turnout had declined since then, slumping to five in December. But LaCree Beasley vowed to keep it going.

Residents of Crockett, Texas, participate in Prayer on the Square on Aug. 20, 2018. Participation in the prayer circle has dwindled in recent months. Photo courtesy Megan Whitworth

She and Bankhead had created the prayer gathering to bring Crockett together, to close the divide, after July’s fiery City Council meeting. But there was dissent even within their attempt to unite. Beasley was part of a movement to boycott businesses owned by people who’d signed the mayor’s petition; Bankhead, it turned out, didn’t believe racism was at play.

“It became to where racism was just having a difference in opinion of someone else,” Bankhead said. “If you had an opinion and you were white, then you were wrong. You kind of gave racism a new meaning.”

LaCree Beasley admitted in January that she and Bankhead were drifting apart because of their conflicting views on the issue. “She didn’t attend the council meeting. I did, so I saw everything that was going on,” Beasley said.

The boycott list was a sticking point for Bankhead. As the list compiled by the Beasley sisters and other Gentry allies grew, it came to mistakenly include businesses whose owners had not signed the petition — including Bankhead’s mother, who owned the recently closed Sears store in Crockett.

“People were complaining that the town wasn’t thriving, but in the same breath boycotting businesses, and it was the black people that were boycotting,” Bankhead said. “There weren’t any white people that were doing it.”

***

An economic blow to the city in January 2019 added fuel to the fight over the CEIDC. An IT company called Provalus had been considering creating 100 jobs in Crockett, and a job fair was held in December. But the company chose another East Texas city, Jasper, leaving Crockett residents indignant and disappointed. Finger-pointing began immediately. Clonts issued a lengthy statement to local media in which she threw the blame squarely at Gentry, detailing ways he and the economic development board had slacked off and missed deadlines to submit paperwork to the company. Gentry and his supporters did not dispute that he and the board missed deadlines, but they said Clonts had initially excluded him from meetings with the company representatives, which city leaders denied.

Things took a turn for the better in March, when the CEIDC helped bring Onshore Outsourcing, another IT company promising 100 new jobs, to Crockett.

Gentry gave a presentation about the company during a City Council meeting in early April. Afterward, four council members congratulated him, Gentry said. Clonts and Calvert didn’t.

Other things struck Gentry as strange. Clonts repeatedly claimed he wasn’t updating the council about the CEIDC’s work, though minutes show he had attended meetings. She sent several public information requests to Gentry’s office asking about the corporation’s debts and Gentry’s salary. Gentry said she could’ve gotten the numbers with a phone call.

Gentry said he’s not quick to pull the race card. When it comes to color, he cares about one color, green — Crockett’s prosperity.

“Forget the hue of my skin, but understand what I’m trying to do here,” he said. “Hear what I’m saying, see what I’m trying to reach for, and stop looking at me so much.”

Gentry grew up in a time when black people had to sleep in their cars when they were traveling because they couldn’t get a hotel room. During his time as a drilling engineer, he worked in Northern states where he was the first black man some people had met, he said.

Gentry said he’s seen racial discord grow in the age of Trump, and he thinks it’s “given a green light for racism to become more of an issue.”

“That is troubling for me,” Gentry said. “I’m old enough to have seen the ’50s, the ’60s, the ’70s. And I was raised in a world that saw some of that negativity. The bad sides. And I don’t want to go back to that.”

***

In July, almost three months after Joni Clonts was voted out of office, the dust was still settling in Crockett.

Tensions had died down, LaCree Beasley said. Without the promise of shouting matches, City Council meetings weren’t drawing large crowds. Everyone seemed to get along better under the leadership of the new mayor, Ianthia Fisher, Beasley said. She and other supporters of Fisher and Gentry believed that voters drove Clonts out of office because they wanted a change; they were tired of her divisive rhetoric.

Other residents seemed less content with the recent turn of events.

On a Saturday morning in late July, several Crockett residents, including a regular at the Moosehead Café, refused to comment on the change in city leadership.

A patron at Rosemary’s Hilltop Kitchen, about half a mile from the town square, said he attends the same church as Clonts and believes she is a “fine woman.” The man asked not to be named in this story. He’s not a racist, he said, but he thinks the May election was rigged and that the City Council fails to get anything done because most of the members are black.

Rosemary Matthews, owner of the restaurant, said she’s sure Fisher will do a “fine job” as mayor. But Matthews, who is white, said residents who voted Clonts out believed the CEIDC conflict “was a racial thing,” something she disagrees with.

“Whether I know all the facts or not … I thought in her heart she was trying to do what was best for Crockett,” Matthews said. “I think they [black residents] feel like, ‘We got a black mayor — we won.’”

Meanwhile, Beasley said she will continue holding the Prayer on the Square.

“It’s a must that you always continue to pray after the storm,” Beasley said, “because you never know what’s ahead.”