Lost in Transition: Rainey Street and a Failure of Historic Preservation

By Jenna Wilson

Reporting Texas

Anita Quintanilla sobbed as her sister drove her back to the airport in 1984. The memories of childhood and adolescence on Rainey Street — the visits to the air-conditioned bookmobile in the dead of summer, and blissful moments running around the spacious yard, raking pyramids of crunchy fallen leaves and climbing cottonwood trees — would be a thing of the past.

When she returned to Austin the following year, the brick building she called home no longer stood at 51 Rainey St. In fact, the entire block was empty.

“I still dream about it a lot,” Quintanilla said.

Due to a struggling economy and developers “waiting for the time for the zoning to turn commercial,” she said the area remained one big empty lot for several years.

Today, only two of the original single-family homes in the Rainey neighborhood remain untouched. Despite national historical designation, a lack of local preservation efforts transformed the once quaint neighborhood into a forest of high rises.

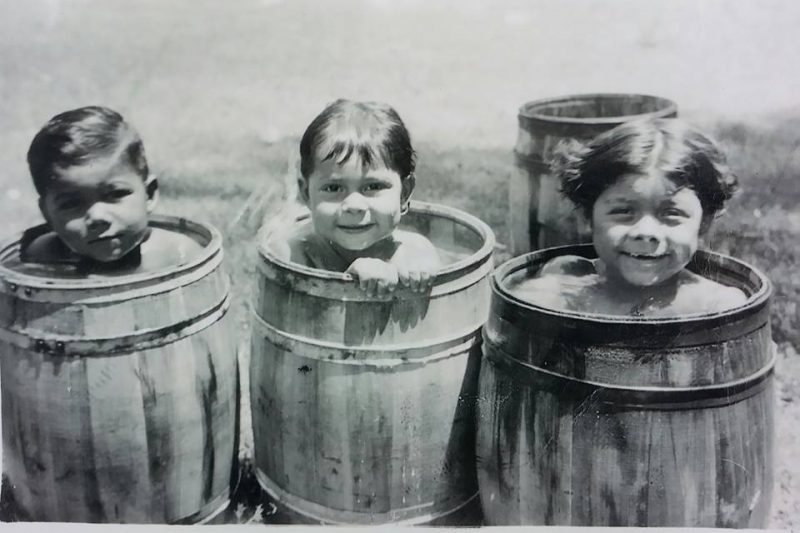

The Quintanilla home at 51 Rainey Street, 1949 (Photos Courtesy of Anna Quintanilla)

Following the completion of I-35 in 1962 that separated the mostly Mexican American neighborhood from the rest of East Austin, developers found a growing interest in the area, and residents took notice.

“I remember watching them build (I-35) and they did separate me from most of my classmates at the Palm School,” Quintanilla said. “It was sort of like a barrier. It was and it wasn’t because you just walked underneath it or over it. But it was there, like a Berlin Wall.”

The Rainey Street residents were working class, mostly blue and pink-collar Mexican Americans who walked to their jobs downtown and white people Quintanilla referred to as “genuine hillbillies.”

“We were all in Rainey Street, we were all poor and all struggling to make it to the next day,” Quintanilla said.

Anna Quintanilla, center, bathing in barrels with her siblings on 1950s Rainey Street

Because residents were primarily poor, she said wealthier people like developers and landlords took advantage of them through buyouts and neighborhood neglect in order to keep property values low.

“They were not fixing up (the area) so that we would get discouraged and move,” Quintanilla said. “That was one of the tactics — neglect the houses until they deteriorate. They wouldn’t make repairs on the rental houses, so they kept deteriorating. People would move out, (the buildings) would be torn down and there would be an empty lot for years.”

To protect their homes, residents and other members of the community fought for protection and won. In 1985, the two blocks running between Rainey Street’s intersections with Driskill Street and River Street, were designated as a National Register historic district. The preservationists ruled that 26 out of the 35 houses contributed to the street’s historic character, but the street was rezoned in 2005 from a residential district to a central business district, allowing bars and businesses to come into the area.

Growing up, Quintanilla said minorities accepted white-dominated American society as “the way it was,” citing a lack of brown faces in TV shows, movies and commercials, and photos of white women displaying hairstyles in Mexican American beauty shops.

“They were all white and people didn’t think much of it,” she said.

It wasn’t until she came to the University of Texas at Austin and joined the Mexican American Youth Organization that she started to realize the power struggles. She associates her years at UT with the time she became “politicized and awakened.”

One memory of “awakening” that sticks with her is complaining to a fellow Chicano at the UT cafeteria about the Austin Aqua Festival boat drag races, where white people would race near hispanics residences, forcing them to deal with the noise, traffic and trash.

“One time I was sitting down, and talking to him and complaining about (the boat races), and he said, ‘Well, why don’t you do something about it?’” Quintanilla said. “Bing! A lightbulb went off. Well, why don’t you do something about it? I had never thought about being able to do something about it, so I was just accepting it.”

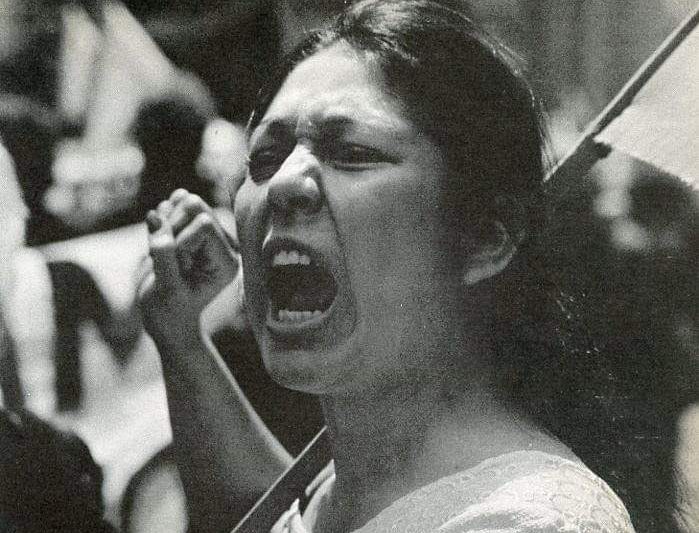

From there, the question “Why don’t you do something about it?” led her to immerse herself in a life of activism, boycotting lettuce and grapes for the farmers, protesting at city hall and attending — sometimes leading — marches, rallies and campaigns.

Anna Quintanilla leading a United Farm Workers march in New York City, May 5, 1975

Today, Quintanilla continues to advocate for Mexican Americans and other marginalized communities. She will serve on the task force for the historic Palm School as it decides what to do with the building and park.

In the years following the 2005 rezoning, all of the original residents of Rainey Street proper either moved or had their homes physically transported to another location. The remaining houses have since been turned into restaurants or bars or demolished and replaced with high rises.

Banger’s Sausage House & Beer Garden opened on Rainey Street in 2012. Owner Ben Siegel said after receiving his building permits, it wasn’t until he applied for a demolition that he discovered the street’s historic preservation status and had to rework his plans. He said Rainey’s designation as an National Register historic district, while also experiencing “the most laxed zoning in the city,” made for a confusing and contradictory process.

“As an individual person trying to (build) something, I got caught in the middle, and that made it very hard,” Siegel said. “Now, 12 years later, it’s a foregone conclusion. Historic stuff got pushed to the side, and (Rainey Street) is very much an extension of downtown.”

Siegel, who is also the president of the Rainey Street Business Coalition, said he sees a difference between gentrification on Rainey Street and other places.

“That gentrification happened on steroids,” Siegel said. “Who can afford that? You can’t. That is true everywhere, but most residential neighborhoods don’t have a zoning change that allows you to build a 50-story building, which is how those property values went crazy like that.”

In Austin, applications to demolish a building within a national or local historic district must be reviewed by the Historic Landmark Commission. If the structure possesses enough historic qualities, the commission can issue a recommendation for the building to be preserved.

However, according to Kalan Contreras, a historic preservation officer for the city, only applicants attempting to remove a building within a local historic district must obey the commission’s recommendation. She said those applying to demolish a structure within an NRHD can ignore the commission’s advice.

“Because our local purview was advisory and Mexican American cultural sites were not on the forefront of preservation, things just kind of spiraled,” Contreras said. “A local historic district overlaid on this National Register district could have put zoning there that could have prevented some of these demolitions. It could have helped us delve deeper into how we treat growth and regulate development in sensitive areas.”

Contreras said the historic preservation department is drafting a new equity-based preservation plan. The most recent preservation plan was created in 1981.

“Preservation as a discipline has evolved for the better, especially with regards to equity and telling the full stories of places,” Contreras said. “When preservation started, (preservationists) were interested in the homes of white, wealthy homeowners with high-style architecture. That’s what people were focused on for way too long, when there was all of this other rich, diverse cultural heritage and architectural fabric that was forgotten because it wasn’t a wealthy white guy’s house.”

Despite the transformation the Rainey neighborhood has undergone over the last several years, Contreras believes its history remains alive.

“There is still a lot more historic fabric in Rainey Street than people realize,” Contreras said. “It’s still pretty intact. It’s not what it used to be, but I don’t think we should give up just yet.”