Journalism Schools Look to Prepare Students to Confront Sexual Harassment

By Sahar Chmais

Reporting Texas

Panelists respond to audience questions during the #WhatNow event on safe workplaces at UT-Austin on Feb. 14, 2019. Brittany Mendez/Reporting Texas

Editor’s note: This story has been updated throughout.

During Alisyn Camerota’s first week at her journalism internship, a news anchor at the organization asked her to dinner and to his hotel room for drinks. Camerota rejected both offers, she says. The next day, in the cafeteria, Camerota says she was spreading cream cheese on her bagel when the anchor approached and whispered in her ear, “Never before in my adult male life have I ever wished I was a bagel.”

Seeking guidance, Camerota confided in a co-worker. The co-worker spread the word to colleagues without Camerota’s permission, she says. When one of her professors read about the harassment in her notes, he commented that it was an “interesting encounter.”

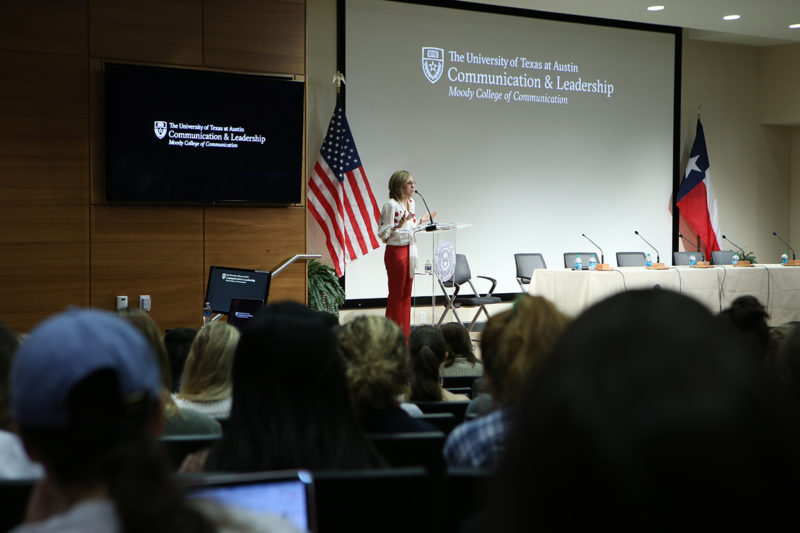

Camerota, anchor of the CNN morning show “New Day,” recounted her experience with sexual harassment during a presentation on developing safe workspaces in February at the University of Texas at Austin. Camerota said she didn’t know how to deal with the harassment she faced as an intern 30 years ago and felt she had no place to turn for help. Now, the advent of the #MeToo movement has opened the door for discussion about sexual harassment, and some journalism schools in Texas have started to address the issue.

CNN New Day co-host Alisyn Camerota presents the keynote address at the #WhatNow event on safe workplaces at UT-Austin on Feb. 14, 2019. Camerota shared her experience with sexual harassment in the newsroom. Brittany Mendez/Reporting Texas

Sexual harassment is an ongoing battle for women in journalism. Almost 80 percent of journalism students at UT-Austin are female, and the statistic is similar at other universities. About two-thirds of women in the field are subjected to sexual harassment, according to Press Forward, an initiative to encourage safe work environments in newsrooms.

Elana Newman, research director at Columbia University’s Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, says journalists should receive training in how to deal with sexual harassment. Although her data suggests that sexual harassment happens most often between co-workers, journalists also have to deal with harassment from sources.

Representatives from the journalism programs at UT-Austin, the University of North Texas, Southern Methodist University, Texas State University and the University of Houston say professors may choose to discuss sexual harassment in classes, and some do, but it’s not a required part of the curriculum.

Texas journalism schools do address sexual harassment in the workplace in a few ways, such as bringing in external organizations like Press Forward to discuss workplace safety and ethics. UNT recently began handing out brochures on sexual harassment to student interns and testing them on the material, UNT journalism professor Tracy Everbach says.

In the past, the curriculum for UT-Austin’s School of Journalism has not contained any formal discussion on sexual assault or harassment, says former school associate director Wanda Cash, who helped write the curriculum. Cash retired in 2016. “I think we can build it in the curriculum either at the [beginning] level, handled in labs, where it’s a little more casual, intimate setting,” Cash said.

Kathleen McElroy, a former editor at The New York Times, was appointed director of the UT-Austin School of Journalism in 2018. McElroy says that, starting in May, she plans to bring trainers from the university’s Title IX office to speak to intro-level journalism students about dealing with unwanted advances. In the fall of 2019, the Title IX trainers will train students during reporting classes. “We are going to have to include sexual harassment training for our journalists before they go into the field,” she said.

Acacia Coronado, a junior journalism student at UT-Austin says this is a good idea. “I think it would be helpful to have a lesson on sexual harassment integrated as one of the fundamentals,” she said, “not just so students are aware, but for resources and limits that they should set.”

Dianna Pierce Burgess, executive director of Press Forward, told UT-Austin students in February during a panel on safe work environments that while awareness of sexual harassment is high among today’s college students, education on how to handle incidents is lacking.

Perla Adame, who works in human resources at the Austin-American Statesman, says people have to learn how to handle harrasment. “One of the first things we ask is, have you asked that person to stop their behavior?” Adame said. “Eighty-five percent of the time people say no.”

Reasons for that, Adame added, could be fear of confrontation, not wanting to be seen as a victim or simply not knowing how to handle the situation. “That’s why it’s important to know how to react and know what to do in the event if you ever find yourself being sexually harassed,” she said.

Burgess and Shiv Ganesh, professor in the Department of Communication Studies at UT-Austin, say they believe the #MeToo movement has opened the door a little more for women to speak up and share their stories. Still, Ganesh said the conversation needs to expand beyond the online realm.

“While digital media are really good at making things visible, they made things visible very quickly and very briefly,” Ganesh said. “Let’s be allies for each other. That’s the only way to get traction on this pressing issue.”

Disclosure: Sahar Chmais, a journalism major at UT-Austin, has taken classes taught by School of Journalism Director Kathleen McElroy.