How Asian Texans Are Working to Improve Their Community’s Political Engagement, Representation

By Jinpeng Li

Reporting Texas

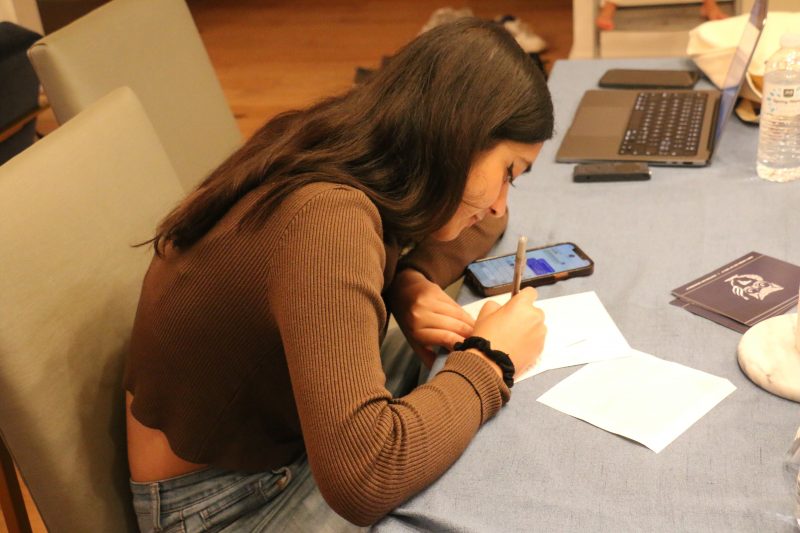

WiseUp TX board member Azra Siddiqi, from left, Rahul Sreenivasan and Alishba Javaid write postcards to get out the vote on Nov. 2, 2022, in Austin, Texas. WiseUp TX is a nonprofit trying to improve engagement of Asian Americans with the voting process. Jinpeng Li/Reporting Texas

As the November election neared, University of Texas student Akeela Kongdara helped to produce an online guide for Asian American and Pacific Islander voters. In Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean, the Asians Texas for Justice guide profiled candidates for governor down to the Texas Legislature, giving their answers to questions on everything from language access to voting rights. More than 1,000 voters read the guide.

It was one of many efforts to improve political engagement among Texas’ growing Asian population. And younger Asians helped to lead the way.

“Younger generation Asian Texans can do more,” Kongdara said. “We can go to our hometowns and make a difference in the political landscape there. We can have our voices heard like if they’re not gonna listen to us in the first place, like just come to us and talk to us, then we have to make noise.”

Asian Americans are the fastest-growing ethnic group in Texas, increasing by 68% to 1.6 million people in the past decade, according to the 2020 Census. But Asians remain underrepresented in the Texas Legislature and other state offices.

Only four Asian Americans will serve in the next Legislature. Asians would have nine seats in the Legislature if they were represented in proportion to their 5.5% of the overall Texas population. No Asian American has ever been elected to represent Texas in the U.S. Congress.

In November’s election, Asian Texans did make some history. Salman Bhojani and Suleman Lalani became the first Muslims and South Asians elected to the Texas Legislature, and Peter Sakai became the first Japanese American to serve as a county judge, winning his race in Bexar County.

“When I faced Islamophobia in my campaign, it was a coalition of African-American, Caucasian and Latino supporters that came to show support at the voting polls,.” Lalani told Reporting Texas. “My charge will be to demonstrate to the diverse families of Fort Bend that an Asian or Muslim who shares their values can represent them as capably as a member of their own community.”

Gene Wu, who is second-generation Chinese, won re-election to represent Texas House District 137 in Houston, a job he first won in 2012. He draws a comparison between Asian representation in Texas vs. California, which has more than 6 million people of Asian descent and 14 people of Asian or Pacific Islander descent serving in its legislature.

He says California’s longer history of Asian immigration has resulted in a stronger Asian voice in politics there. Texas’ Asian population only began to swell with an influx of Vietnamese refugees in the early 1980s.

“That’s the reason why Asian Americans always stay silent and find it hard to engage in the public realm,” Wu said. “It hurts our ability to deal with problems.”

He’s seeing signs of progress in Texas, but it’s been slow. When more members of the Asian community get involved in the political process, either through running for office or taking appointed positions, “then we will get more political power,” he said.

“Asian Texans need a stronger base of support,” Wu said, “One of the big things that I tried to do is make sure that Asians get political appointments, not elected. But when people come to me, say, give me some names of Asian people to appoint to this position. I called around and found nobody’s interested.”

WiseUp TX board member, Azra Siddiqi, sorts through postcards encouraging Asian Americans to vote. Jinpeng Li/Reporting Texas

WiseUp TX is trying to improve that engagement. The nonprofit founded by Azra Siddiqi, an Austin lawyer who has worked in state government, encourages South Asians to get involved in government by providing information on polling locations, the voting process and candidates. This year, it produced a podcast to help spread the word of how these policies impact Asian Texans.

“Those people are deciding the policies and politics of your day-to-day life,” Siddiqi said, “I feel like our community is more reactive than proactive. But at certain times our community could have been the deciding and swing vote on some districts.”

Siddiqi says the lack of engagement works both ways and that many elected officials do not engage with Asian communities.

“I was chasing down politicians to come on our podcast, which has been a great transition in terms of reaching out to us,” Siddiqi said. “But some of them still don’t reach out to us, don’t get to know our views, don’t want to know what’s important to us.”

“Most elected officials do not know how to reach out to the Asian community and do not know how to talk to them,” Wu said. “The most basic step is showing respect to the community. The next step would be to talk with the community and engage the community and see what they want and see what their concerns are.”

Those concerns include harassment and other acts of racism against Asians. Texas saw the fourth-highest number of anti-Asian incidents between March 2020 and March 2022, according to nonprofit organization Stop AAPI Hate.

Lalani thinks having greater representation of the diverse Asian communities of Texas serves to help blunt the spread of hate. “A common thread is; we have all felt the sting of racism and exclusion. So when someone tries to use race, creed, religion, or color to divide or disparage a community, the response is remarkably uniform — a complete and furious rejection of hate,” he said.

Alishba Javaid, the youngest member in WiseUp TX and the president of the University of Texas’ chapter of the Asian American Journalists Association, writes a postcard to her friends and family and urges them to vote in Austin, Texas, on Nov.2, 2022. Jinpeng Li/Reporting Texas

“We can’t wait for anti-Asian incidents to happen and then get motivated to fight for our rights,” said Alishba Javaid, the president of the University of Texas’ chapter of the Asian American Journalists Association.

Javaid said she became politically active after high school, but she sees lingering generational differences.

“My parents, like other immigrant parents, care more about politics back home than U.S. politics,” said Javaid, whose parents are from Pakistan. “But I’ve been wanting to get them to care more about U.S. politics. Even if you don’t tune into it, it’s still affecting you whether it’s city politics or federal politics.”

She and other younger Asians are trying to help their community be more engaged. Before the November election, Javaid said she wrote 38 postcards to her friends and family members, who are all in Asian Texans communitiesy, to encourage them to go vote.

Kongdara, who produced the voters guide, said her organization hosted eight phone bank and text bank events to make sure Asian Texans were ready to cast ballots.

Kongdara grew up in an immigrant town in Amarillo full of Chinese and Southeast Asians. “I realized there is a much larger community out of Amarillo that needs help,” she said, “Putting all interests towards the AAPI community advocacy work for me is a way to give feedback.”