House GOP Tax Bill Could Squeeze Graduate Students’ Finances

By Scott Squires

Reporting Texas

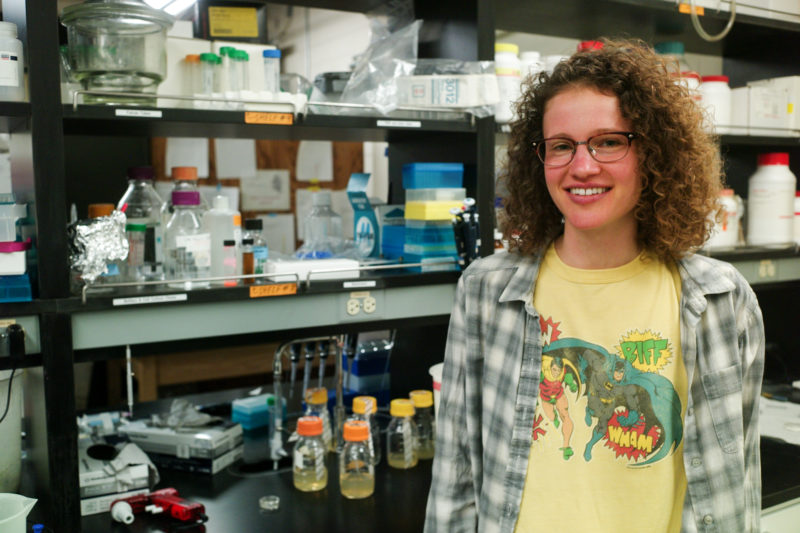

Suzanne Jacobs is a second-year PhD student in biophysics at the University of Texas and an assistant instructor in the physics department, and worries that a provision in the House tax bill will hurt her financially. Scott Squires/Reporting Texas

Suzanne Jacobs, a second-year Ph.D. student studying biophysics at the University of Texas at Austin, gets animated when talking about bacterial slime.

“When you have certain types of bacteria swimming around in a fluid, you can put that fluid on a gel, which suddenly dries them out,” said Jacobs, who is 28. “Then the bacteria do this thing where they suck up fluid from the gel and make slime, and then can move through it.”

Jacobs’ research potentially could contribute in fields as varied as pharmaceuticals to oil and gas engineering. Like most doctoral students, she supports herself by working as an assistant instructor, in her case in the physics department.

“For me, coming back to grad school was a dream come true,” Jacobs said. “And then this little tax thing comes up.”

The U.S. House of Representatives on Nov. 16 approved a dramatic change to the tax code that would reduce tax rates for corporations and individuals and eliminate many popular tax breaks. It also would add $1.4 trillion to the deficit over the next 10 years.

One provision would make graduate students pay taxes on tuition waivers, which now are not taxed. Universities award the waivers and stipends to some graduate students in exchange for them working as teaching or research assistants. The waivers offset the cost of tuition, reducing student loan debt and giving students some measure financial stability.

Under the House Republicans’ Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the taxable income of many graduate students could grow by tens of thousands of dollars. The University of Texas Graduate School estimates that many students could see between a 100 and 400 percent increase in their taxes in the next year if the House bill becomes law.

The tuition waiver stipulation is not in the Senate version of the bill, which is expected to come up for a vote Thursday. It’s not clear whether the provision would end up in the final bill if both chambers approve. But graduate students across the country are planning a nationwide walkout Nov. 29 in protest.

“I don’t think I would be financially independent” if the House version passes, Jacobs said. “I’d have to find another job. Most people I know are in the same boat.”

Nearly 145,000 graduate students nationwide received tuition waivers from 2011 to 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Almost 60 percent were graduate students in science, technology, engineering and math.

“Actually, we’re a really good deal for what we do,” said Kristin Kovach, a biophysics Ph.D. student who shares an office with Jacobs. “We’re highly qualified, and we’re cheap labor.”

UT-Austin’s tuition waivers are on par with the national average—almost $11,000 annually for master’s students and around $13,600 for doctoral students. But many of the UT’s 3,000 master’s students and 900 Ph.D. students who receive tuition waivers would be financially squeezed by the tax change.

Both the House and Senate bills would raise the standard tax deduction from $6,350 to around $12,000 for a single person. That may not be enough to offset the cost of tuition for many students. Many doctoral students are in school for five or more years. Students from other states, who already pay higher tuition, would be hit hard. Out-of-state grad students pay between $16,400 and $19,000 a year, depending on the program.

Samantha Fuchs is legislative director of the Graduate Student Assembly at UT. Scott Squires/Reporting Texas

Samantha Fuchs, an environmental engineering Ph.D. student, receives a $25,000-a-year tuition waiver. Fuchs, who studies geological methods to capture atmospheric carbon dioxide, is also legislative director of the Graduate Student Assembly, the official representative body for UT graduate students.

“My taxes are going to go up by $3,000,” she said.

Fuchs, who makes $22,000 a year as a research assistant, would see nearly $6,400 withheld from her award every year under the House proposal, according to the Graduate Student Assembly’s calculation.

Although she would get some of that back as a refund, the tax hike would cut into her budget for rent, groceries and trips home to see her family.

“I really can’t get my personal costs down much further,” she said.

The House bill also would eliminate the federal tax deduction that allows students to write off up to $2,500 a year in student loan interest.

“Students are hit hard by this plan,” said U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke (D-El Paso), who, along with every other House Democrat, voted against the bill. He said the House version “will have a negative impact on those Texans using student loans, grants and graduate work to afford the increasing costs of higher education.”

Spokespeople for Texas’ U.S. senators, John Cornyn and Ted Cruz, said they could not comment on how they would vote on the Senate version.

Republicans likely included the tuition waiver item in an effort to raise revenue to offset other tax cuts the standard deduction increase, according to Neal McCluskey, education analyst at the Cato Institute, a Libertarian think-tank in Washington. He said lawmakers may see tuition waivers as “de facto income,” even thought the money never enters students’ bank accounts.

But McCluskey said that taxing tuition waivers would be “terrific education policy.”

McCluskey said that academic institutions would be forced to “remove the ridiculous degree of inflation that you see on tuition prices, so the prices would reflect what is actually charged.”

“What schools say they’re going to charge is very rarely what students pay, because they give tuition discounts, students loans, grants and Pell grants,” McCluskey said.

Students would pay more out of pocket, and fewer would be able to afford post-graduate education, making graduate degrees more valuable on the job market, he said.

Joseph Guidry is a freshman astronomy major, and is planning to go to grad school to study astrophysics. “College students have it hard enough already,” he said. “This tax bill will only make it harder for grad students to support themselves.”

“That’s an argument we’ve been hearing on the Hill, but it’s one that fundamentally flawed,” said Samantha Hernandez, director of legislative affairs for the National Association of Graduate-Professional Students in Washington.

Because public universities are funded differently from state to state, it’s not a given that universities across the country would lower tuition. Instead, students would likely have to take out even more loans.

“The fact of the matter is that a program like this is going to cut out thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of graduate students from getting their degrees,” Hernandez said. “This is just sending the message that if you can’t afford tuition, and the taxes on that tuition, you don’t belong in graduate school.”

Joseph Guidry, a freshman astronomy major at UT, worries that the tax bill will further burden graduate students already saddled with debt and make graduate education unaffordable for many low- and middle-income Americans.

Guidry dreams of becoming an astrophysicist and plans to pursue a Ph.D. in the future. Without a research stipend, he’s not sure he’d be able to afford it.

“My future would be in peril,” he said. “This captures a really alarming trend of anti-intellectualism that has been festering among the American population.”

Some of the tax bill’s detractors say the provision is part of a large-scale attack on social institutions.

“Universities, hospitals, mass transit, you name it,” said James Galbraith, professor of government at UT’s LBJ School of Public Affairs. “The idea is to limit deductions and make the middle and lower-middle class pay for massive tax breaks for the very rich.”

“Education should be available to everyone,” Samantha Fuchs said. “If you want a well-educated population, Congress has to realize that they have to be funded in order to survive.”

Students who already are far along in their programs will likely have to take on more student loans. But for Ph.D. students early in their academic careers, now might be a good time to enter the workforce with a master’s degree, according to Jacobs.

But that’s not what many grad students signed up for.

“We’re smart people,” Kovach said. “We could go get a job making a lot more money right now, but we made the choice to go to grad school and not be super rich because we liked it enough.

“I think this country is going to lose a generation of people that would have gone to grad school to come up with new ideas and help move our country forward. Now, people are not going to have the space to do that because it’s not going to be economically viable.”