Harm Reduction Services Struggle to Tame Austin’s Accelerating Opioid Overdose Rates

By Corey Smith

Reporting Texas

Clayton, a substance user who has been helped by a harm reduction program, strums his guitar in Austin, Texas, on Oct. 9, 2022. His full name has been withheld upon request. Corey Smith/Reporting Texas

Standing in a gravel lot, sun pinned high in the October sky, Steve sees his former self as he makes his daily rounds through a homeless encampment filled with people grappling with substance use disorder. When he is approached by a man in the camp who admits his recent struggles with substances, Steve offers advice in the form of an analogy.

“It’s a process, man, like making steel,” Steve tells him. “You know how steel is made? They don’t just pull out a slab and call it done. You pull out the molten steel, chip away at it, then put it back into the furnace. Pull it out, chip away at it, put it back into the furnace.”

Steve is clinic coordinator for a harm reduction team, one of several in the Austin area that continues to chip away at a crisis plaguing drug users. With overdose deaths mounting, groups like Steve’s are providing overdose reversal medications and other supplies to ensure safer substance use and generally healthier living.

But the groups operate in a legal gray area, which explains why Steve doesn’t want his full name or even the name of his organization to be published.

“This work is important for everybody here,” Steve said after a day of outreach in his group’s mobile clinic. “Don’t you know we all can go to jail right now? Because everything that we do is illegal, technically. When I was doing the (safe syringe exchange) van, all of that stuff on there was illegal. But guess what? Ain’t never stopped me.”

Steve’s group takes its clinic van, funded through a state grant, to several encampments each Tuesday through Friday, providing Narcan nasal spray, an opioid overdose reversal medication, safe smoke kits, needle exchanges, hygiene supplies, wound care kits and Plan B contraception pills.

The organization also offers a “drop-in center,” a house in East Austin that provides free food, clothing and hot showers.

“This helps a lot actually,” says Joe, a substance user and participant in the program, who envisions one day purchasing land to house himself and others. “If I didn’t have access to this place, personally, my life would still work, but everything would be just a little more difficult. It makes me feel a little more civilized and human. Being homeless, little things let you hold onto that humanity… like eating a meal at a table. That’s a big one.”

Volunteer Sarah Todd, assembles a bag of wound care supplies which will be distributed through a mobile outreach program as part of a harm reduction program. Corey Smith/Reporting Texas

Harm reduction teams are playing an increasingly vital role as drug overdose deaths rise, primarily related to drugs spiked with fentanyl, a particularly potent synthetic opioid. The Travis County medical examiner reports a 73 percent rise in overdose deaths in six years, from 178 deaths in 2015 to 308 in 2021.

In June, the Austin City Council unanimously declared the overdose epidemic a “public health emergency” after the 2021 Travis County Medical Examiner Annual Report identified drug overdoses as the leading cause of accidental death in the county, killing two and a half times more people than car crashes during the preceding year.

The City Council proclamation directed the city manager to ensure that all of the city’s first responder vehicles are equipped with naloxone, a medicine that rapidly reverses opioid overdoses and to improve access to harm reduction services and to medication-aided treatment to assist people in safely coming off opioids.

“Today was a good day because I haven’t heard about anyone dying,” Steve said after a recent community outreach event. “That’s very few and far between, I can’t remember the last day like this one.”

Deaths related to fentanyl rose from 214 in 2018 to 1,672 in 2021, according to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Travis County reported 113 fentanyl-related overdose deaths in just the first half of 2022, nearly matching the total from all of 2021.

A harm reduction program volunteer displays test strips used to identify fentanyl, which can alert drug users to its presence in other drugs. Corey Smith/Reporting Texas

The Drug Enforcement Administration says fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. Fentanyl-detection strips, which alert users to the presence of fentanyl in another drug, are among the resources offered by harm prevention teams.

But the test strips remain categorized as illegal drug paraphernalia under the Texas Controlled Substances Act, in effect since 1973. The same law prohibits clean needle exchanges are also illegal in Texas. Harm reduction organizations are urging the Texas Legislature to repeal drug paraphernalia laws and authorize syringe service programs when it reconvenes in January.

Some Texas politicians have been critical of harm reduction efforts, approaching individuals’ struggles with substance use as more of a moral issue than one pertaining to health care, and that rigidity is largely reflected in the state’s laws around substance use.

“It literally is the case that the Biden administration is giving out free crack pipes because this will be good for America if everyone’s smoking crack,” U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, said during a February episode of his podcast. “You know, talk about a great crime policy, as many people on crack as possible. These are your Democrats.”

Cruz was commenting on one aspect of the Biden administration’s $30 million Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration harm reduction grant program. Among its strategies for lessening the effects of the opioid crisis is providing safe smoke kits containing alcohol swabs, Vaseline, plastic mouth pieces and new glass pipes, each of which can help protect substance users from transmissible infections, including HIV.

“During my training, I learned that the program was illegal but tolerated by the City of Austin,” said one harm reduction volunteer. “Since the program started, we haven’t had any direct issues with the police. They tend to turn a blind eye. But I soon learned that participants, if caught with certain supplies, can face consequences.”

When asked whether Austin Police Department enforces laws concerning drug paraphernalia, a department spokesperson pointed to the department’s General Orders for officers, which states that under Texas state law, “Class C misdemeanor citations may be issued to subjects found in possession of drug residue” and that any “object with drug residue shall be seized and submitted.”

Dr. Crispa Aeschbach Jachmann, medical director for Addiction Psychotherapy Services in Austin, Texas, says ‘large swaths’ of the state have virtually no access to the services her office provides. Corey Smith/Reporting Texas

Dr. Crispa Aeschbach Jachmann, medical director for Addiction & Psychotherapy Services, the oldest private methadone clinic in Austin, says numerous obstacles stand in the way of people seeking legal routes to lessening the risks accompanying opioid use.

Methadone, one of three federally-approved medications for opioid use disorder, has been found in National Institutes of Health studies to be especially effective in staving off relapse, yet for many this solution remains too expensive or difficult to access, given the scarcity of clinics.

Aeschbach Jachmann says there are “large swaths” of the state with virtually no access to the types of services her office provides. Clients travel to Austin for treatment from as far as Laredo, where a single methadone clinic serves a population of over 260,000.

“Fundamentally, harm reduction is about saving people’s lives and increasing safety around unsafe behaviors,” said Aeschbach Jachmann, who categorizes her clinic’s services more as a long-term treatment option than a harm reduction resource. “The harm reduction community has been very vocal about making changes, and there’s a lot of focus on just the rights of people who use substances.”

Experts say public stigma about drug use limits wider use of harm reduction health care which can help users such as Clayton who is also experiencing homelessness. Corey Smith/Reporting Texas

“If everyone who did an opioid turned blue for four days, people in this country would be really surprised about how close substance use disorder is to them,” said Lama Naomh Tomás, a former substance user and current volunteer staff member at Turning Point Recovery Center in Bellows Falls, Vermont.

“I know a lot of people in recovery that can’t say they’re in recovery,” Tomás said. “We would be amazed that this group includes some of the most wonderful people we know, but because of jobs, relationships, community status and stigmatization, a lot of people don’t.”

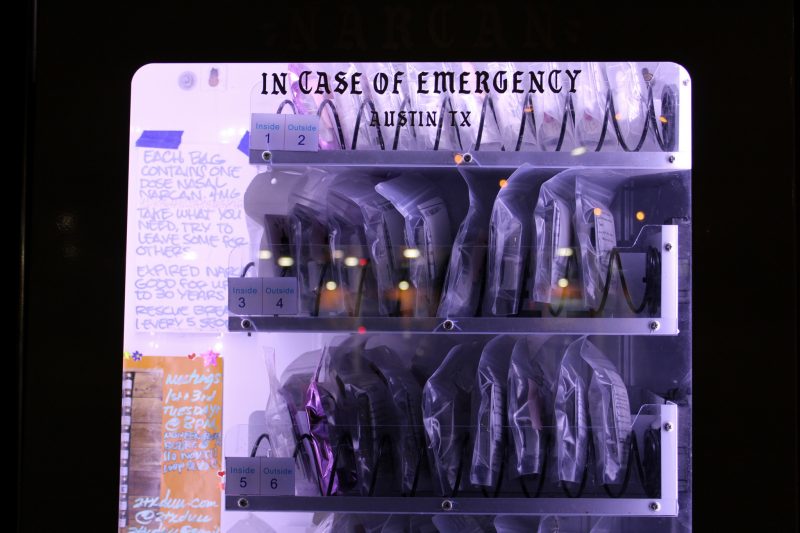

A recently stocked Narcan vending machine glows in the night at Sunrise Community Church in Austin, Texas. Corey Smith/Reporting Texas

There are some indicators of more progressive local drug policies taking shape, including installation of Austin’s first public Narcan vending machine in August at Sunrise Community Church in South Austin.

The machine, which is accessible 24 hours a day, was built by the Austin-based N.I.C.E. Project (Narcan In Case of Emergency) in partnership with the Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center and funded through a $2,500 Austin Mutual Aid grant.

“Some of the population we serve, they experience a tremendous amount of pain: lack of sleep, a lack of housing, and this resource provides a level of safety and comfort,” said Rob McCabe, lead community housing navigator for Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center.

“But the kind of people accessing the vending machine span the entire socioeconomic spectrum,” McCabe said. “It’s kind of surprising to see some of the moms from West Lake Hills coming down in their Mercedes to get four or five doses.”

Narcan nasal spray, the first product of its kind to be FDA-approved for emergency treatment of opioid overdose, sends naloxone molecules to the brain, where the molecules may displace opioid molecules from opioid receptor sites to help reverse life-threatening effects of an overdose, according to the product’s site. Naloxone only has an effect on the body for 30 to 90 minutes, and multiple cartridges are needed in cases where an overdosing person does not respond within minutes of receiving a dose.

In October, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said the state must find ways to distribute Narcan to make it more readily available to Texans exposed to fentanyl. “We’ll need to look for the areas where fentanyl is found most predominantly and make sure Narcan is easily available there,” Abbott said.

The reach of the harm reduction movement continues to widen, meanwhile, with three Texas organizations receiving federal grants of $398,960 in 2022 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to fund their work, and dozens of similar organizations operating across the state.

“It’s huge, and it’s gonna be in more places,” Steve said of increasing community access to Narcan. “We only can work so many hours a day. It should have happened a long time ago. It would’ve happened a long time ago if it was up to us, but we’re better off now than we ever have been.”