Effective Parenting Program Aims to Reduce Truancy in Travis County

By Swathi Narayanan

Reporting Texas

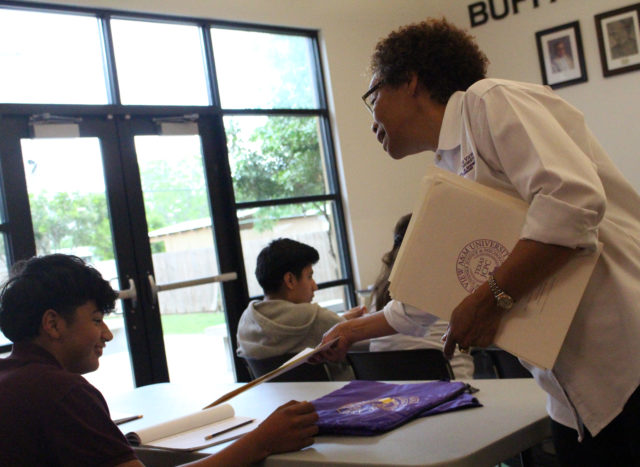

Grady Paris teaching in the parents and child engagement workshop. Josefina Mancilla/Reporting Texas

On a recent Wednesday evening Jennifer James sat in Precinct 1, the Justice of the Peace office on Heflin Lane in East Austin, looking anxious, as she waited for her son, Hector Prado.

Hector’s habit of skipping school had prompted administrators at Webb Middle School to file a truancy charge against the eighth-grader, and now he appeared to be AWOL yet again.

On this night, Hector and his mother were scheduled to attend the precinct’s Effective Parenting Workshop. Its goal is to help truant youth stay in school and their parents avoid possible criminal penalties under Texas law.

When James told workshop organizer Grady Paris that Hector wasn’t picking up his phone, Paris said, “Call him from my phone.” But before the call could go through, Hector walked in and apologized to his mother for being late.

“He did the right thing by apologizing to you as soon as he came,” said Paris, as she patted Hector on the back. Prado nodded his understanding. “I need to get focused on what I have to do,” he said.

According to the Texas Judicial Council, over 65,000 truancy cases were filed in Texas in 2014. But there are efforts to curb truancy and bring errant students back to school — and perhaps build stronger families in the process. One development came in 2015, when the Texas Legislature decriminalized truancy for school-age youth. Students rolling up 10 or more unexcused absences may still be ordered to appear in civil court, where they face a combination of mandatory counseling, community service and court costs of up to $100. Parents, however, can face criminal charges of Contributing to Nonattendance, if the county can prove their child’s truancy results from parental neglect. Rulings can carry a fine of up to $587. If the fine isn’t paid, a contempt of court citation could lead to a maximum of three days in jail.

“The primary intervention before the law changed was a fine and criminal conviction,” said Deborah Fowler, executive director of Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit organization that works with low-income families. “What changed last session was not only a shift away from using criminal court sanction and conviction… [but also making] the process look more like what we would see in a juvenile court — which is a civil process. The system for the parents remain relatively unchanged.”

Schools in Travis County file truancy cases with the Justice of the Peace Courts. When students are sent to court, they may be charged with a civil offense called “truant conduct.” In 2014, Travis County’s five Justice of the Peace precincts fielded a total 2,004 such cases, 19.7 percent of those, or 395, came through Precinct 1, according to the Texas Office of Court Administration. To combat its truancy cases (there were 468 in 2011 – 2012; and 515 in2012 – 2013) Grady Paris, a training specialist at the Texas Juvenile Crime Prevention Center at Prairie View A&M University, teamed up with Yvonne Williams, a college friend who currently serves as Precinct 1 justice of the peace, to create the parenting workshop.

The purpose of the workshop is to ensure that parents and children communicate more effectively among themselves, said Paris, 63. All too often, she said, “Even if they [parents] are talking, they are talking at the child and not with the child.”

Yvonne Williams, Justice of the Peace of Precinct 1 in Travis County, speaks with a student. Josefina Mancilla/Reporting Texas

When Williams, 61, took office in 2011, she said she quickly saw the challenge in Precinct 1’s “tremendous truancy docket.” Her jurisdiction includes 49 public and charter schools in a sprawling area that incorporates East Austin, Pflugerville and Del Valle. It has consistently ranked among the county’s truancy hot spots.

Williams reached out to Paris, and, in the course, of a conversation, the idea of creating a communication workshop emerged. Today, the program features two-hour sessions every Wednesday for four weeks. On Thursday morning there is a separate session for parents against whom cases have been filed.

The Effective Parenting and Child Engagement Program works as a form of intervention, after a school has filed a case against a child. Administrators may also use it as a preventive measure and agree not to file a truancy case with the county if the participants complete the workshop.

Its school-age participants may benefit from the program by having their court costs and administrative fees waived. Parent fines may be reduced to $100 or less, depending on economic need.

Paris said it takes her two hours to drive from her home in Prairie View to reach Precinct 1, but she gladly makes the weekly drive for the chance of helping reduce the truancy numbers.

“I will come,” she said,“rain or sleet.”

During the sessions, Grady stresses to attendees the importance of doing things together as a family and then asks them the following week to tell her about their family interactions. Participants also role-play to help them cope with real-life situations.

The parenting workshop fits in with Precinct 1’s overall efforts.

“Judge William’s court is one that we frequently cited as a model when we were advocating for reforms at the legislature,” said Fowler, of Texas Appleseed. “She is really interested in trying to make sure… that she is addressing the problems in a way that she is not going to see the kids come back to the court.”

According to Precinct 1 senior planner Eleanor Thompson, the parenting workshop costs $54,000 per school year. Much of the funding comes from the Texas Juvenile Crime Prevention Center at Prairie View A&M, with which the precinct has a formal agreement.

Since it started in 2011, more than 800 families have attended the workshop, though the program has so far generated little data to suggest how effective it is in keeping children in school.

But the numbers tell only part of the story. When children come to the court, Thompson said, “they are told we are not here to punish you. We are going to help you — if you will let us.”