Despite Risks, Grape Growers See Texas as Ripe for Investment

By Louise Rodriguez

Photography By Emree Weaver

Reporting Texas

Jim Kamas, horticulturist at Texas A&M’s Agrilife Extension research lab in Fredericksburg, Texas.

FREDERICKSBURG — They come in swarms like a biblical plague, zeroing in on grapevines heavy with ripening fruit.

“The sky just rains sharpshooters,” Jim Kamas, horticulturist at Texas A&M’s Agrilife Extension research lab in Fredericksburg, said of the crop-destroying insect.

“Early in the season, we don’t know where they are,” Kamas said as he walked toward the lab’s research plot full of fruit trees and grapevines. “But then around Memorial Day for some reason, something changes and they flood vineyards.”

Tackling pestilence is hard enough, but Texas grape growers across the state also face erratic weather that alternates from drought to floods to crop-killing, late-spring frost. So it’s surprising that Texas is experiencing a surge in winery enterprises—and not all interest is home-grown.

A Pierce’s disease resistant grape variety called the Victoria Red was named for its consistently successful growth in Victoria, Texas.

The Texas Hill Country is the second most-visited wine region in the U.S., and Texas’ wine industry is ripe for more growth, said Justin Scheiner, professor and extension viticulture specialist at Texas A&M’s department of horticulture. The industry’s direct economic impact in Texas has reached $4.5 billion in total goods and services as of this year, as reported by the economic research firm John Dunham and Associates.

California producers burdened with astronomical real estate prices, groundwater restrictions, droughts and recent devastating wildfires have begun sending out feelers in Texas’ grape-growing regions, which are mostly in Central Texas and the High Plains around Lubbock. Winemakers like Napa Valley’s Robert Mondavi Winery have already begun inquiring about land, according to Kamas.

“They talk about how much easier it would be to grow grapes in Texas,” he said.

Kamas had just finished inspecting bright yellow sticky cards clipped to the lab’s wire fences for the pest that chokes the life out of grapevines: the glassy-winged sharpshooter. But this day in mid-November he found none. Instead the cards are coated with graveyards of flies and moths. In the past, Kamas said, he’s seen a local card with 300 sharpshooters attached.

A sticky trap full of sharpshooters, the insect that spreads Pierce’s disease. The traps are attached to the fences surrounding the grapevines fruit trees at Texas A&M’s Agrilife Extension research lab.

The half-inch-long sharpshooter carries inside its mouth a bacterium that causes Pierce’s disease, a deadly infection spread when the insect, a type of leafhopper, feeds primarily on the woody part of the grapevine. Leaves of affected plants turn paper-bag-brown, and fruit shrivels.

“If you were going to say what is the No. 1 limiting factor to grape production in Texas, (it would be) Pierce’s disease,” Scheiner said.

Texas is not alone in its fight. California growers have also been dealing with rampant Pierce’s disease. By hitching a ride on Texas nursery material nearly two decades ago, the glassy-winged sharpshooter, endemic to the U.S. Gulf Coast, found a new home in Southern California. The insect made its way north to the state’s wine country and attacked susceptible grapevines and fruit trees in the state responsible for 85 percent of wine production in the U.S.

“They recognize that it’s a very serious threat to the industry,” Scheiner said.

In 2004, Texas A&M researchers, with funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, participated in an emergency project to help California growers manage Pierce’s disease. Texas became a natural laboratory for the research.

Sharpshooters can be found in vineyards across Texas, Kamas said, but their impact depends on the climate and variety of grapevines planted. The insects flourish particularly on the state’s warm, humid Gulf Coast. So growers there mainly plant two disease-tolerant varieties: Blanc de Bois, which is a native American species crossed with European grapes, and a hybrid called Black Spanish that includes a native Texas grape species.

The problem is that most Texas winemakers today aspire to producing higher quality wines, leading growers to experiment with riskier European varieties such as hot climate-loving Italian, Rhone and Spanish grapes, Scheiner said.

When he first started work in the Texas Hill Country in the 1990s, Kamas said, the region had only seven vineyards, all planted with non-tolerant grape varieties.

“And every single one of them had Pierce’s disease,” Kamas said.

An epidemic like that can kill entire vineyards, forcing farmers to mitigate damage or rip out vines and start over with new plantings. Establishing just one acre of grapes in the Texas Hill Country costs between $25,000 to $30,000, Kamas said.

Kamas looks out at the grapevines in the lab’s research plot, which are dormant this time of year. The lab grows and tests disease-resistant grapes in order to advise grape growers in the region.

Three years ago, researchers from University of California, Davis estimated the annual cost of dealing with Pierce’s disease in California at $104 million, with over half of that tied to lost production and vine replacement.

Treatment for Pierce’s disease—an injectable virus that kills the xylella fastidiosa bacterium—is expected to be commercially available by 2019, said developer Carlos Gonzalez, a Texas A&M professor of plant pathology and microbiology. Its status as a green alternative satisfies California environmentalists and the wine industry, he said.

“Many of the expensive wines (in Northern California) keep an organic label,” Gonzalez said. “So they can’t use pesticides.”

Kamas experiments with Victoria Red grape variety on research land in Fredericksburg.

The treatment is under review by the California Department of Pesticide Regulation and the Environmental Protection Agency. But until it hits the market, Texas grape growers follow Texas A&M viticulture advice, which is to plant disease-resistant grapes and keep other sharpshooter-host vegetation away from vineyards.

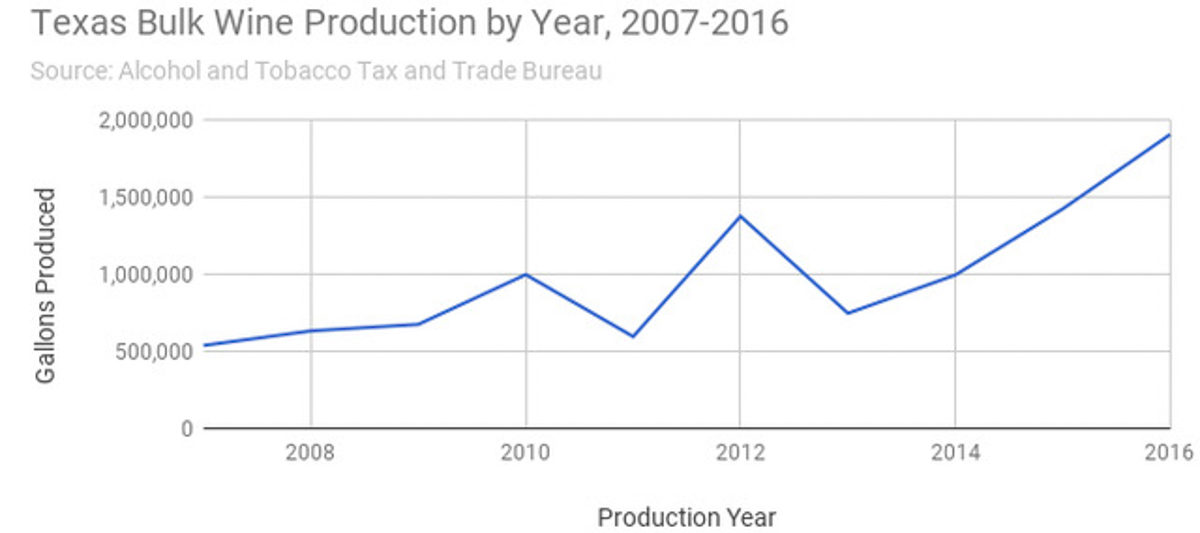

With Pierce’s disease well managed in Texas for the time being, the wine industry continues to thrive. The U.S. Department of the Treasury ranks Texas as the 11th-largest wine-producing state in the country. But with the number of Texas winery permits expanding tenfold to 454 in the past 15 years, the state’s wine production will be on a steep upward trend, Scheiner said. In the past decade, the state’s bulk wine production climbed from over 538,000 gallons to nearly 2 million gallons.

“You have no idea how many prospective growers we have,” Kamas said.

Doug Lewis and his college roommate Duncan McNabb learned about viticulture while working at a Hill Country winery in 2009, and three years later, the two used the experience to start their own winemaking business in Johnson City.

Starting out—before the seven-acre Lewis Wines vineyard even existed — Lewis and McNabb entered into a co-op-type arrangement where they produced wine using grapes from an established Round Mountain vineyard. He and his staff continue to work with several growers who need help with pruning or training vines in exchange for credit down the line during harvest, Lewis said.

Making wine tends to be a “retiree job” in Texas, Lewis said. “A lot of cool things happening in Texas (wines) right now are coming from a young wave of producers.”

Lewis takes chances planting varieties that are untested for the region, including a Portuguese grape called Arinto.

Doug Lewis, co-owner of Lewis Wines in Johnson City, describes some of the wines they have available for tastings. He first became interested in the wine industry after working at Pedernales Cellars in college. Lewis and his business partners then built their winery in 2012 before having their first harvest in 2013.

“I was kind of sweating on this one,” Lewis said. “I know no one’s grown it in Texas before.”

Another change arriving along the Hill Country’s Wine Road—U.S. Highway 290—is more scale: bigger winery investments and larger plantings. Kamas predicts that soon, 50- to 100-acre estates will dwarf the 5- to 10-acre vineyards along 290.

Not everyone is excited about that.

“Maybe things would get more expensive” if California growers moved into Texas, Lewis said. “There’s still more land I’d like to buy before it goes too high.”

Passage of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014, which empowers local agencies to regulate groundwater extraction, has added another economic burden on growers who already were contending with ever-ballooning land values.

Lewis samples a new wine they are working on.

California growers most likely would buy in Texas’ leading grape-producing region, the High Plains, Scheiner said. An acre there goes for $1,100 to $2,250, as reported by Texas Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers. Plantable land in California’s Napa Valley is listed by vineyard and winery sales broker Vintroux at $25,000 to over $200,000 per acre.

But new wineries would be walking into a battle brewing in the Texas High Plains between established cotton farmers and vineyard owners over herbicides that harm grapes.

“It’s gotten really contentious,” Kamas said. “The cotton people are telling the grape people, ‘We were here first.’ Not very neighborly.”