Data Mapping Unlocks New Approaches to Community Health Issues

Children’s Optimal Health staff Susan Millea, Maureen Britton, Nic Moe, Mohan Rao, and Octavio Ulloa review maps of neonatal care in Travis County. Photo by Oscar Ricardo Silva.

By Ian Floyd

For Reporting Texas

Health officials in Travis County are creating programs to reduce pregnancy complications and birth problems in neighborhoods east of Interstate 35, using data mapping tools that identified hotspots for those issues.

The programs focus on teenage African-American mothers, who the data showed have a high incidence of problems such as premature births, low-weight babies and little access to prenatal care.

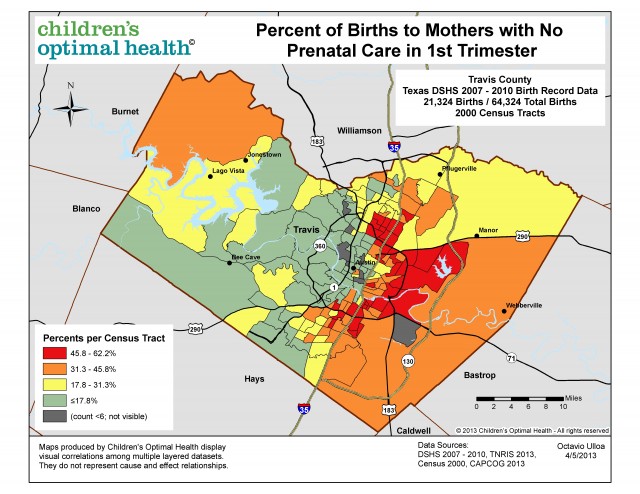

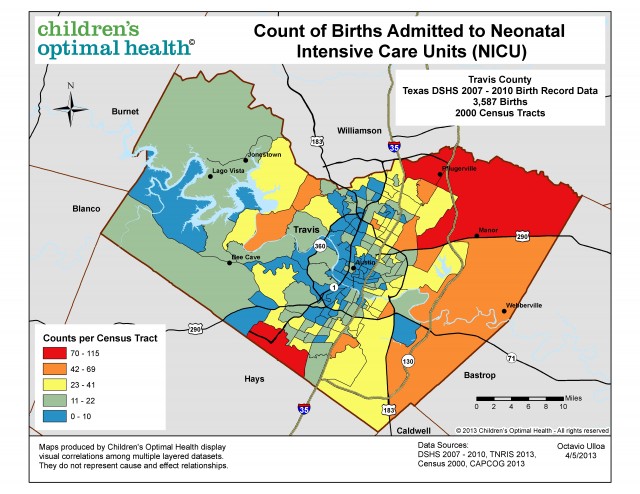

The Maternal and Infant Outreach program is based on research from Children’s Optimal Health. The coalition of 13 Central Texas organizations uses census and health data, and geographic information systems, or GIS, technology to create maps that pinpoint areas with a prevalence of problems. The maps can zoom in to the level of census tracts or neighborhoods, depending on the data, and help identify contributing factors such as low incomes and limited access to care.

This approach to community health gives agencies a way to aim money and programs at areas with the biggest need. The maps become the basis for discussions among community members and health care professionals about how to design specific programs to address specific problems.

By identifying factors that contribute to health problems and the populations most affected, “we can figure out how to do better outreach to the target populations where we are seeing those high needs,” said Susan Millea, the lead researcher on the project and a co-founder of Children’s Optimal Health.

COH was created in 2008. It previously developed maps for issues such as childhood obesity, adolescent substance abuse and car-seat usage.

For the problem pregnancy research, Millea and her colleagues overlaid census data, state birth records and two indices measuring adequacy of prenatal care to reveal that 26 percent or more of pregnant women in areas straddling and east of I-35 did not receive prenatal care in their first trimester. In North Austin, near Rundberg Lane, the maps showed high rates of problem births.

Teenage African-American mothers were more likely to have pregnancy complications compared with mothers of other ethnicities. For example, 77 of every 1,000 babies born to those mothers were admitted to neonatal intensive care – the highest rate of any ethnicity and nearly double the rate for white babies.

It costs an average of $45,000 to treat a baby admitted to neonatal intensive care, compared with about $2,500 for a regular birth, according to COH.

The Austin-Travis County Health and Human Services Department in November launched the Maternal Infant Outreach program, which includes small-group discussions among affected mothers and health care professionals to zero in on the causes and obstacles to getting neonatal care.

The department is also creating programs for underserved pregnant Latino women, said Tim Eubanks, a project manager for the department.

“We are seeking to develop these programs through classes, focus groups, community conversations—anything where we are hearing directly from those communities that let us know what’s going on,” he said.

CommUnityCare, a group of 22 Austin-area community health centers, will use the research to shape other programs. Two of the clinics offer informational programs for pregnant women aimed at reducing premature births.

“When we offer gynecology and prenatal care, we are very conscious that our patient population may not be as educated or knowledgeable about the best way to manage the pregnancy and have a healthy outcome,” said Elizabeth Marrero, community relations manager for the health centers.

The COH research was what the organization needed to improve its programs, she said.

“We may see the need in our clinics, but we don’t always have the numbers to show that we should divert some money to create a program here or there,” she said. “This research was able to show that in a very clear way.”

It is difficult and time-consuming to obtain the data, and COH must find partners to finance the mapping and the follow-up programs. The organization received birth records for Williamson and Hays counties when it obtained the Travis County data, but needs money to proceed with the research in those areas. The organization worked with the Texas Department of State Health Services to receive the data, with personal identifying information deleted.

The problem pregnancy research was paid for in part by a $25,000 grant from the RGK Foundation in Austin, which funds educational and medical research. Children’s Optimal Health gets sustaining support from organizations that include the Seton Family of Hospitals, the St. David’s Foundation, the H-E-B grocery chain, the University of Texas at Austin, Lone Star Circle of Care health care centers, and the Austin Independent School District.

The systematic targeting of populations in need can be broadened beyond the boundaries of a county to the state or even the country, Millea said.

“This kind of approach could certainly be applied in a larger geography,” she said. “The data is available.”