Chronic Pain Patients Say Restrictions on Prescription Opioids Too Stringent

By Sahar Chmais

Reporting Texas

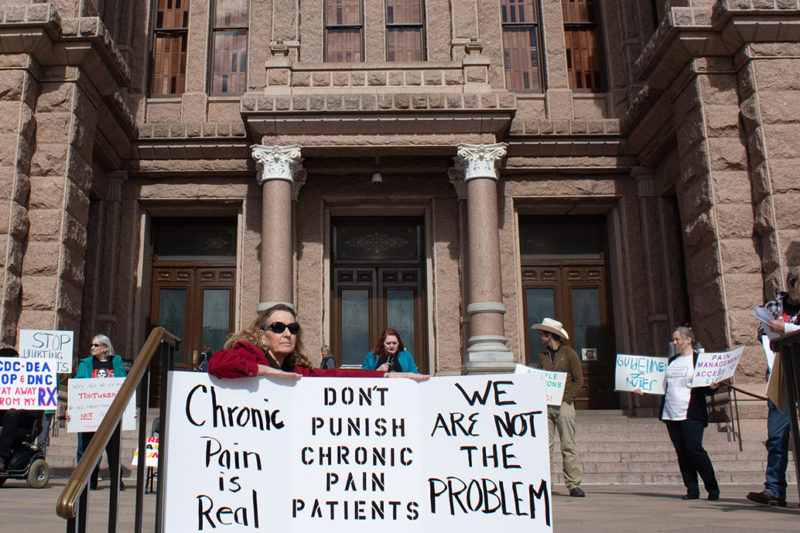

Sherri Martin speaks at the Don’t Punish Pain rally on the south steps of the Capitol in Austin, Texas, Jan. 29, 2019.

Some Texans who suffer from chronic pain say they are being denied needed medication because of federal guidelines limiting the prescription of opioids. About two dozen of these patients participated in a rally dubbed Don’t Punish Pain, an offshoot of a national movement, at the Texas Capitol in late January to bring attention to the issue.

“Taking a law-abiding citizen’s pain medicine away … there’s no logic to that,” said rally attendee Julia Heath, a 49-year-old retired physician assistant who has fibromyalgia, a disorder that causes chronic pain.

Opioid abuse has skyrocketed during the last decade. On average 130 people die every day from opioid overdoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2016, the CDC tightened guidelines for prescribing the drugs in an effort to curb opioid abuse. Rally attendees said a lack of access to medication since the guidelines took effect is diminishing their quality of life and has even caused some chronic pain patients to resort to suicide.

Opioids are a class of drugs that includes fentanyl, heroin and prescription medications such as hydrocodone. Between 8 and 12 percent of patients who are prescribed opioids for chronic pain develop an addiction, according to a 2015 meta-analysis of dozens of drug studies.

Addiction to this class of prescription drugs has become a major public health crisis and has devastating consequences for addicts, says Dr. Chad Dieterichs, an anesthesiologist at Capitol Anesthesiology in Austin.

“The problem isn’t the people that need the medicine, the problem is the people that are abusing and selling the medicine,” Dieterichs added. “The law is punishing the people that need it.”

Kevin Teckenbrock, 46, suffers from a degenerative bone and joint condition, and his hip bones are progressively being ground down, he said. Because of the CDC’s tighter guidelines, his doctor is decreasing his pain medication and some pharmacists have refused to fill his prescription, he added.

“I can walk about 20 feet. I’m still in a tremendous amount of pain, but the pain meds allow me to do simple things,” Teckenbrock said.

Nancy Wheeler listens to a speaker at the Don’t Punish Pain rally on Jan. 29, 2019, in Austin, Texas.

Dr. John Harvin, a professor of surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, told Reporting Texas that he understands the government’s effort to rein in over-prescription of opioids, but some prescribing guidelines may need to be re-evaluated.

“Any sort of crisis leads to an overreaction,” he said. “Some of the regulations are thoughtful and some seem to get in the way of doctor-patient relation.”

Pain medication shouldn’t be the first line of treatment for chronic pain patients, Harvin said, but some patients have been on such medication for years and rely on it to function. It’s hard to argue with those results, he added.

Nancy Wheeler, 64, has undergone eight back surgeries. She used to partake in physical therapy at an office and now does the exercises at home daily. As the CDC has cracked down on opioid prescriptions, Wheeler’s doctor has reduced her medications “to a point where if he goes any lower,” she said, “the quality of life is definitely going down.”

“I can’t take my pain without help. I don’t want to go down a different road,” Wheeler said, referring to suicide.