At Mexic-Arte, Activists and Artists Pay Tribute To Chicano Movement, Culture

By Pamela Hall Vance

Reporting Texas

A mural honoring the late community activist Paul Hernandez is pictured on the walls of the Mexic-Arte Museum. The mural was painted by Amado Castillo III and his son. Jamie Roy/Reporting Texas

East Austin community activist Paul Hernandez left such an imprint on Austin that his image adorns the walls outside Mexic-Arte Museum. The mural’s completion coincided with the opening Friday of an art exhibit dedicated to the Chicano political and civil rights movement of a half-century ago that sought to end discrimination against Mexican Americans.

The photographs at the entry of the exhibit, “Chicano/a Art, Movimiento y Más en Austen, Tejas 1960s to 1980s,” capture Hernandez and other activists in the Austin community working to bring about change.

“This is really history and art combined,” said Cynthia E. Orozco, professor of history and humanities at Eastern New Mexico University and sister to Mexic-Arte executive director and co-founder Sylvia Orozco.

That history included protests in 1978 after years of complaints from East Austin residents about noise and pollution caused by boat races during the city’s annual Aqua Festival on Town Lake, now known as Lady Bird Lake.

Connie Arismendi, left, and Chris Cowden, right, admire work by artists Pio Pulido and Sylvia Orozco during the exhibition on April 8, 2022 in Austin. Jamie Roy/Reporting Texas

“So we had a big protest,” Austin City Council Member Sabino “Pio” Renteria told the audience from a crowd of about 200 at Friday’s Mexic-Arte opening. “We had the boat race protests that finally got them out of our neighborhood.”

A series of photographs by Manuel “Chaca” Ramirez shows the tension and turmoil of the moment.

Other artwork reflected the movement in different ways. Artist Luis Guerra’s homage to the 1977 Texas farm workers’ march from Austin to Washington D.C. is also in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The marchers formed picket lines in D.C. to earn bargaining rights for the Texas farm workers. A newspaper image of the same artwork is displayed in a showcase beneath the print. Guerra marched in the Austin portion with Texas union leader Antonio Orendain, who is pictured in the artwork.

“I marched with them for three days,” Guerra said at Friday’s event. “I walked with them when they were here with my daughter on my shoulders.”

Renteria recalled that Orendain always dressed in black and wore a cowboy hat and a wooden cross, just as he is pictured in a photograph in the exhibit.

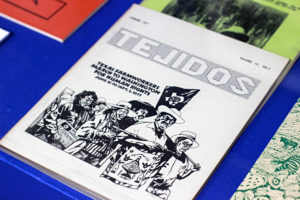

Guerra’s print was featured on the cover of “Tejidos, a Bilingual Journal for the Stimulation of Chicano Creativity and Criticism.” One section of the exhibit contains several of the journals and other pamphlets and books dedicated to the Chicano culture and movement during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“Tejidos, a Bilingual Journal for the Stimulation of Chicano Creativity and Criticism.” Edited by Raquel Elizondo and David Cavazos. Jamie Roy/Reporting Texas

“A lot of the visual artists that are exhibited here today are published in ‘Tejidos,’ “ noted David Cavazos, one of the journal’s editors. “So their work is actually archived in the Library of Congress. I think that’s very cool. Because that kind of stuff lives on forever.”

Album covers with the music of the day were also featured in the exhibit, and some of the members of the band that played during Friday’s opening reception were activists.

“We wrote our music for the movement,” said 75-year-old musician Jose Flores. He was a member of the band Conjunto Aztlan, which recorded a song for the Smithsonian Institution’s CD of Chicano movement music.

Jose Flores, 75, sings with the band Conjunto Aztlan. Jamie Roy/Reporting Texas

When asked about the meaning of the exhibit, he said, “They’re all my friends and neighbors. I grew up when you could have some of this stuff for a six pack. We were all friends and still are.”

The University of Texas at Austin was represented at the exhibit by artists and activists.

“I felt very fortunate that the kind of activism and practice that they advanced in the city is what welcomed me on my arrival in the late 1990s to start my doctoral work,” said Ramón Rivera-Servera, now dean of the UT College of Fine Arts. “So you should know that you can do art and politics at the University of Texas now.”

Linda Del Toro, who was active politically on the UT campus in the ‘70s and is now a real estate broker, said the art “reflects the empowerment of the Chicano community during that time.”

Artist Janis Palma recalled being a UT student in the ‘70s. “It was a very effervescent time. We were marching with the farm workers. We were doing murals with the community, teaching children art, we were very very involved as students not only with us, but also with the community at large. So it was … a constant awareness raising activity for us through our art.”

Austin resident Marión Sanchez smiles while listening to Sylvia Orozco speak. Sanchez has been collecting Chicano art since the 1980s, including pieces from artist Sam Corodado. Jamie Roy/Reporting Texas

Photographer Pedro Meyer donated a major work by the entrance of the museum entitled “La Reyna America.” His images from the Conferencia Plastica Chicana, held in Austin in 1979 to showcase Chicano art, were also shown.

“What you’re doing here is an archive for future generations,” Meyer said. “And I think that that is significantly as important as the art itself.”

Another photographer, Alan Pogue, has many images in the exhibit. Pogue was an Austin photojournalist who focused on social justice and Texas politics. His images include a black-and-white photograph of a young female Brown Beret, which was a civil rights organization. Activist Paul Hernandez, who died two years ago, helped form the local chapter.

Bob Perkins, a 74-year-old retired state district judge, attended Friday’s exhibit and noted Pogue’s work. “I enjoyed very much the black and white photographs that are there at the beginning when you first walked in because they were talking about the Ku Klux Klan rally and all those other kinds of things,” Perkins said. “And I remember that I signed an injunction preventing the Ku Klux Klan from marching and put it off for like a week or two, because the Austin Police Department had come and asked for an injunction because they weren’t prepared to guard the streets.”

The show also features abstract art and pictures with big bold colors such as the one by José Treviño that graced the cover of the exhibit. Amado Maurilio Peña, known for his Southwestern artwork that has an indigenous influence, was included. There were also murals that once covered buildings long gone in downtown Austin.

Renteria said that the exhibit can remind young people that they are able to be a power and have an influence on social justice. It brought back a lot of memories and helped him realize that “the struggle was worth it.”