A Quiet Place of Rest for One of Texas’ — and Baseball’s — Best

By Aaron Schnautz

Reporting Texas

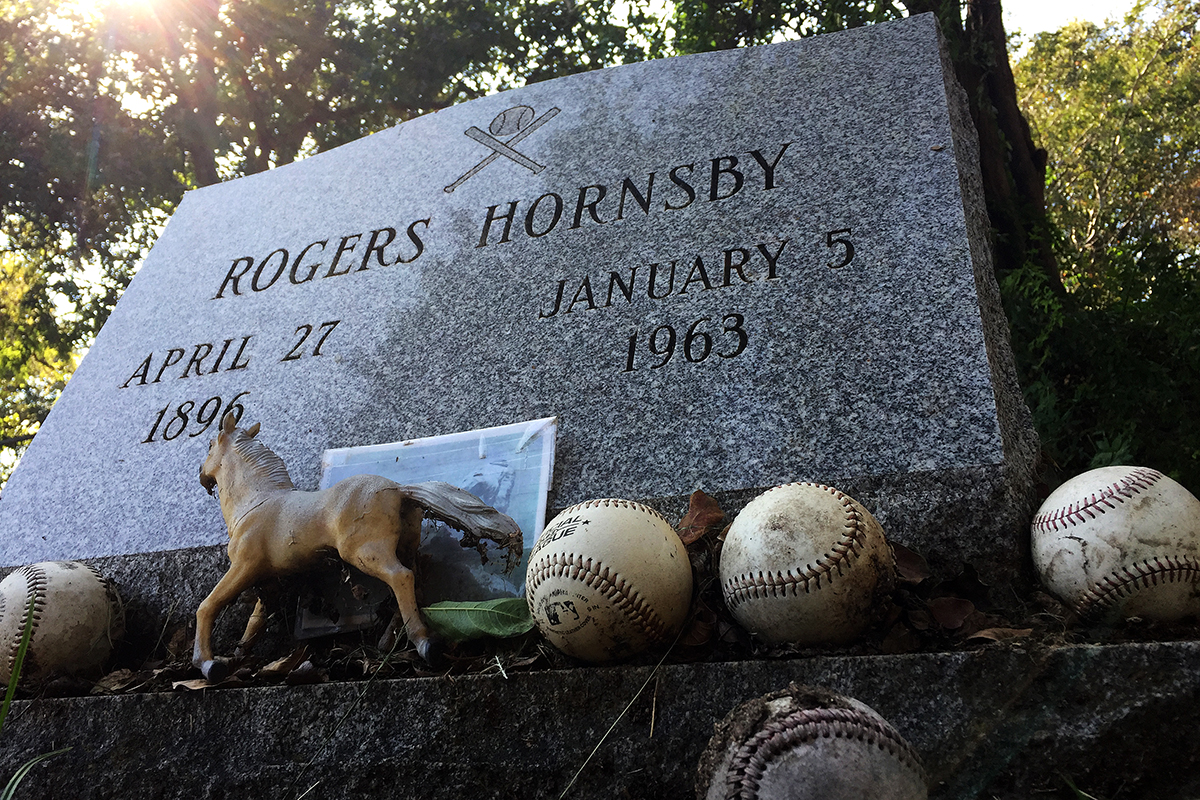

Hornsby’s headstone serves as a pilgrimage for diehard baseball fans. Among the gifts fans have left behind are baseballs, a small plastic horse and a laminated photo of Hornsby tagging out Babe Ruth to end the 1926 World Series. Aaron Schnautz/Reporting Texas

Austin’s best-kept baseball secret lies off of FM 969, just east of Blue Bluff Road in eastern Travis County. Behind a metal gate, posted with signs to deter vandals, a narrow gravel path twists half a mile downhill toward the Colorado River and a time long forgotten.

Mesquite trees and cacti block the view on each side. Visitors pass a 1936 Texas Centennial marker commemorating the first house built in Travis County before the path opens to a field that is home to one of the oldest cemeteries in Texas.

Nine miles east of the capital, after the skyscrapers fade from view and congested city streets open to country highways, dedicated baseball fans and history buffs can find the final resting place of Rogers Hornsby, one of the greatest baseball players ever.

The 27th inductee of the National Baseball Hall of Fame was born in 1896 in Winters, Texas, the youngest of six kids. “The Rajah” signed with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1915 and would amass 2,930 hits, including 301 home runs, during his illustrious 23-year career. His .424 batting average during the 1924 season is a record that still stands today. At .366, Ty Cobb is the only player to better Hornsby’s .358 career average.

“Not many people know his grave is there,” said Hugh Hornsby, Rogers’ first cousin once removed.

Hornsby Cemetery is just a small part of Hornsby Bend, named for the family patriarch, Reuben Hornsby. As a surveyor for Stephen F. Austin, he spotted land along a northern bend in the Colorado River and relocated his family. In 1832, he established the first permanent white settlement in what would later become Travis County.

Rogers Hornsby, one of the greatest players in Major League Baseball history, is buried in Hornsby Cemetery nine miles east of Austin. The two-time MVP still holds the National League record for highest batting average in a season. Aaron Schnautz/Reporting Texas

The cemetery became necessary four years later when Texas Rangers John Williams and Howell Haggett died guarding the Hornsby property from Comanches. They were the first of 467 interments at Hornsby Cemetery, which includes 13 other Texas Rangers and veterans of conflict ranging from the War of 1812 to Vietnam. More than 360 of the graveyard’s residents can trace their ancestry to the Hornsby family patriarch.

The biggest attraction is the star baseball player, Reuben’s great-grandson.

Rogers died of a heart attack in Chicago on Jan. 5, 1963, after complications from cataract surgery. He was buried in Hornsby Cemetery five days later, on a cloudy and unusually warm winter day. Family, friends and colleagues from his nearly 50 years in baseball poured in from across the country to mourn the loss of the Hall of Famer.

“The cemetery was packed,” Hugh Hornsby said of the burial service. “It was the most people I had ever seen at a Hornsby funeral.”

They laid him to rest near his family: Aaron Edwards Hornsby, his father who died 20 months after Rogers was born; William Wallace and Emory Bud Hornsby, his older brothers who wouldn’t live long enough to see him become the National League MVP; and Mary Dallas Rogers Hornsby, his mother and namesake who passed away three days before the start of the 1926 World Series – the only championship Rogers won.

He took baseball seriously. He avoided alcohol and tobacco. He slept upwards of 12 hours a day and drank whole milk with every meal. He even refused to read books or go to the movies for fear of straining his eyes.

Boston Red Sox legend Ted Williams, who knows a thing or two about hitting, called him “the greatest hitter for average and power in the history of baseball.”

But his headstone says little. There is no mention of his two MVP awards or the seven batting titles he won. Nor is there mention of his two Triple Crowns or his World Series victory. The unpretentious foot-high grave marker simply lists his name and dates of birth and death. The lone indication that baseball meant anything to Rogers Hornsby is the ball and crossed bats engraved above his name, and the tributes visitors have left over the decades.

“Ever since the funeral, there have been baseballs on that tombstone,” said Ronny Platt, another great-great-great grandson of Reuben Hornsby and president of the Hornsby Cemetery Board of Governors for the past eight years.

Rogers’ grave became a baseball pilgrimage site. A recent trip to the cemetery found a handful of gifts on his headstone: six worn baseballs, the oldest of which had turned gray and was coming apart at the seams; a faded laminated photo of Hornsby tagging Babe Ruth for the final out of the ’26 Series; and a small replica horse, possibly representing his reported fondness for gambling on ponies.

There are no written messages, no names or dates to say who visited when. There’s no guestbook to sign, no tour guide. There are simply two centuries of history to sift through before finding the most decorated headstone in the cemetery.

“Nobody knows how long things get left there,” Hugh Hornsby said. “Usually if something disappears, something else replaces it pretty quickly.”

Rogers’ headstone is by no means the largest or flashiest at the cemetery. It lacks the historical markers that interest Karen Thompson, the president of Save Texas Cemeteries Inc. She occasionally sends researchers to Hornsby Cemetery to study the plaques and medallions adorning the grave sites of some of the most important people in Texas history. Although her focus is typically on the headstones representing the Daughters and Sons of the Republic of Texas, Thompson makes an observation each time she passes by the greatest right-handed hitter in baseball history.

“I don’t know how many folks visit Rogers’ grave,” she said. “But enough that a fairly new baseball always seems to be there.”