Human Trafficking: Slavery in our Backyards

[stream flv=x:/reportingtexas.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/revHumanTrafficking.flv img=x:/reportingtexas.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/revHumanTrafficking.jpg embed=false share=false width=640 height=360 dock=true controlbar=over bandwidth=high autostart=false /]

By Julie Chang

Promised a quality American education and enough money to entice any poverty-stricken child to want to leave home, 11-year-old Given Kachepa traveled from his village in Zambia for what he believed was a better life. The next two years would prove otherwise, as his new home in a small town outside of Dallas, Texas became his modern-day slavery.

“I was very excited about this opportunity,” said Kachepa, more than a dozen years later. “Because when you grow up poor and you don’t have anything in your life, and here comes this opportunity that was going to change it, who is going to turn something like that down?”

Kachepa is just one of an estimated 600,000 to 800,000 human trafficking cases worldwide each year, according to the US Department of State report in 2006. Of the 7,637 calls made to the National Human Trafficking Hotline in 2009, the highest percentage of calls (12 percent) came from Texas, according to the Polaris Project, the organization that operates the hotline. Texas is a prominent transit state for human traffickers, providing both a gateway and a destination for victims. Trapped in a web of fraud and coercion, the trafficked victims brought to the US are forced into servile labor or the sex industry.

“There is a general belief that slavery has been abolished, so when you start to talk about being enslaved today in 2011, most people can’t absorb that in a way that makes sense,” said Noël Busch-Armendariz, a professor at UT’s School of Social Work.

Orphaned at nine years old, Kachepa was trafficked into an all-boys a cappella group run by a now defunct Christian ministry from Sherman, Texas, a city about 70 miles north of Dallas. Kachepa, along with 11 boys, were forced to perform four to seven concerts per day, traveling across the state often without breaks or even food. Although the boys’ families were promised money, and a Zambian town a new school, the ministry never sent a dime back home. According to documents obtained by CNN, the ministry called TTT: Partners in Education earned $1 million in performances, sponsorships, and donations, in just one year.

Human Trafficking in Central Texas

[kml_flashembed publishmethod=”static” fversion=”8.0.0″ movie=”https://reportingtexas.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/humanTrafficingMap2.swf” width=”640″ height=”480″ targetclass=”flashmovie”]

[/kml_flashembed]

But Kachepa’s story differs from the majority of human trafficking cases found in Central Texas, which usually involve forced prostitution. In the past six months, the Austin Police Department has investigated about 30 cases of human trafficking, all of which involve women and children from the US or countries south of the Texas-Mexico border, said Billy Sifuentes of APD’s human trafficking unit. The typical ages of victims are 12 to 25.

“It’s not poverty that brought them to slavery; it’s the trafficker. Poverty brought them here because they want to make a good life and do good for their family,” said Sifuentes. “But nobody can ever tell us or this unit that people come into this country to become a slave.”

Billy Sifuentes is a member of the APD Human Trafficking taskforce, the largest of its kind in the state. Photo credit: Joshua Barajas

Depending on the origin, trafficked victims are trapped through different means. Domestic trafficking of Americans occurs more frequently than foreign trafficking, Busch-Armendariz said. Experts say that American victims usually come from troubled home environments—those with substance or physical abuse and neglect. Traffickers target the vulnerable on the street or shopping malls, luring their victims into romantic relationships and eventually enslaving them.

“From the stories we have researched, the ones that have been in the news, the survivors we’ve talked to, they come from all walks of life,” said Austin-based Michelle Nehme, the director of the domestic human trafficking documentary called “Trade in Hope.” “There’s definitely at-risk populations, and runaways tends to be in that risk group.”

Lies, Fraud, and Coercion

Foreign victims like Kachepa are typically promised a legitimate job, usually in a restaurant or in manufacturing, or as a nanny.

Sifuentes said that local cantina owners are one of the masterminds behind human trafficking in Austin. They hire legal residents to travel across the Texas-Mexico border to find a girl, gain her trust under the false pretenses of money and love, and smuggle her illegally into the US. Upon arriving, traffickers threaten the girl into prostitution, using the cantina as a way to lure customers.

“Lot of the time, it’s threats. ‘We’ll kill your family; we’ll kill your little sister; we know where you live’,” said Nehme. “It’s enough to make these young girls comply.”

In a 2006 case in Austin, traffickers handed out business cards with various code words that solicited illicit sex. Photo credit: APD

In a 2006 case in Austin, Sifuentes said that traffickers solicited business cards outside of bars, grocery stores and meat markets that catered to immigrant populations. The different business cards, many of them with the same phone numbers, advertised establishments like “Young and Old Repairs” or “Sweater of Skin” Tejano clothing—euphemisms for illicit sex. Then, sexual activities would occur in apartments, duplexes, trailer homes, or even spas and massage parlors.

“They solicit on business cards with code words and passwords,” said Sifuentes. “They’ll give you a card and say, ‘We have flores chiquitas.’ That’s code word for children.”

Traffickers have become increasingly technologically savvy in finding victims. Sifuentes said that traffickers are constantly changing their IP addresses to avoid being tracked on the Internet while also advertising on new Craigslist offshoots like Backpage.com. In the last six months, two cases in Austin have involved traffickers finding victims on Facebook where friendly or romantic relationships developed.

Multibillion-Dollar Goldmine

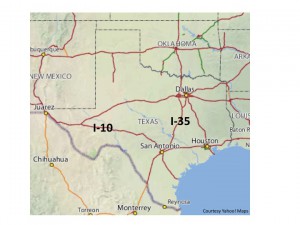

But it’s no surprise human trafficking has become a sophisticated industry in the state. Rates of human slavery are on the rise, experts say, with IH-35 and I-10 as major routes in Texas for a multibillion-dollar goldmine. Experts predict that human trafficking brings in more money than trafficking of weapons, and falls just behind drug trafficking. Sifuentes said that while a one-time transaction of kilogram of cocaine in Austin goes for about $24,000, a trafficked victim can make about $1,000 per week for many years – for their pimp.

The federal government estimates 18,000 to 20,000 victims are trafficked into the US each year. Since 2001, 20 percent of the identified victims of human trafficking have been in Texas. This is because of Texas’s close proximity to the border, its gulf ports and Interstates, I-10 and I-35.

“What traffickers bank on is that they can sell a person over and over whereas they can sell drugs or a weapon only once. It’s lucrative for them,” said Laurie Cook Heffron, a professor at UT’s School of Social Work.

Shame are often deterrents to escape, said Heffron. Kachepa’s traffickers frequently threatened to deport the boys back to Zambia, which Kachepa said would have meant losing face in the village. That was enough to keep the boys silent and resigned to a hopeless fate.

“The important thing was that we didn’t want to go back to Zambia,” said Kachepa. “We understood that if we gave up, then we would be shunned in the community. A lot of people in the village would have given up a lot to have what we had—to get to the United States.”

The psychological trauma associated with trafficking has led to concerted efforts among law enforcement, medical and mental services, and social workers to treat rescued victims. The Central Texas Coalition Against Human Trafficking aims to raise awareness and rehabilitate victims. Common effects of trafficking range from mental trauma like depression or loss of trust to the unfamiliarity of doing daily tasks like grocery shopping or using a bank account.

“They lose an ability to trust people,” said Heffron, who is a member of the Central Texas coalition. “The world has been juggled and they have been kept out of balance especially for foreign-born victims.”

Sifuentes said that the majority of trafficking investigations are unsuccessful because victims fear coming forward. Despite the enacting of state law prohibiting human trafficking in 2003, prosecutors rarely press human trafficking charges because it’s harder to prove. Instead, they might use more established and easily provable charges like ‘compelling prostitution’ or ‘unlawful restraint and kidnapping’ to bring forward prosecution. Those charges will usually land a maximum sentence of 25 years in jail.

“Historically, county prosecutors have always seemed reluctant to use new laws for the fear of losing an important case,” said Sifuentes. Sifuentes said that 25 years is a very good term for a crime like human trafficking that is relatively unknown among juries.

No Room for Heroes

Kachepa’s traffickers were prosecuted through a roundabout means too. Keith Grimes, the pastor who brought the boys to Texas and forced them to work, died of natural causes before the boys were rescued. After the boys were rescued by immigration services and eventually placed in foster care, a criminal investigation started. In 2000, TTT ministries were forced to pay $966,000 in backwages, but nobody from TTT ministries received jail time.

Today, Kachepa’s relationship with his village in Zambia is still contentious. Kachepa said that they believe that his speaking out about his trafficking experience has ruined the village’s means of sending boys to the US. Although he misses his family in Zambia, Kachepa said that he hopes to help people in the future, dividing his time between the US and Africa.

[audio:https://reportingtexas.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/01-Kimulena-He-Is-Worthy.mp3|titles=01-Kimulena-He-Is-Worthy]Kachepa, who is in his first year of dental school at Baylor in Dallas, continues to sing. He said that healing is a process and that he has forgiven TTT for the years that they had stolen from his childhood, but he hasn’t forgotten the trauma.

“I don’t have a hero. It would probably be Jesus if I had one,” said Kachepa. “He was the only who hasn’t disappointed me. ”