Texas Separatists Aim to Go Mainstream

By Aimée Knight

Reporting Texas

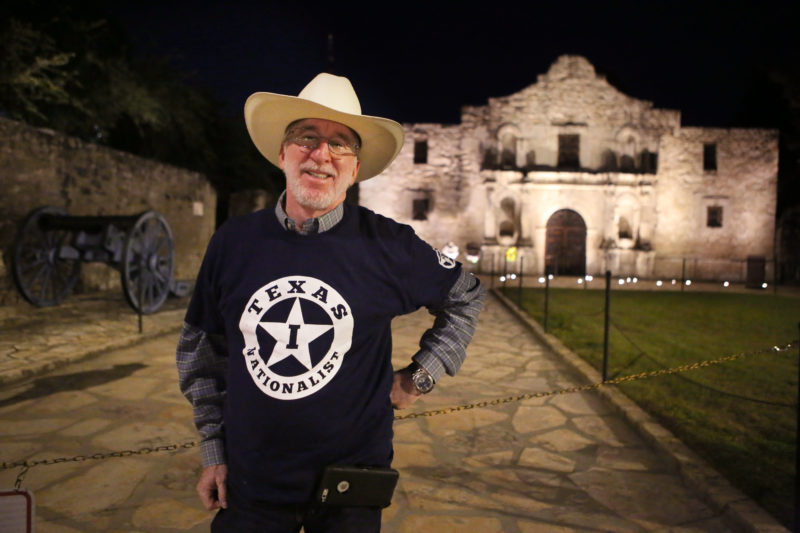

Coordinator Karl Gleim pauses after laying a wreath after the Texas Nationalist Movement’s monthly march around the Alamo in San Antonio on Nov. 9, 2019. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas

Five men march in military formation around the Alamo in downtown San Antonio. Led by a man shouldering an enormous Texas flag, they wear the Texas Nationalist Movement’s march uniform: a dark blue shirt with the letters of “Texas” adorning each point of a star and a Sam Houston quote emblazoned across the back. It reads: “Texas will again lift its head and stand among the nations.”

Texas Nationalist Movement members walk toward the Hipolito F. Garcia Federal Building and United States Courthouse in San Antonio as they begin their monthly march around the Alamo on Nov. 9, 2019.

Some wear wide-brimmed hats in the cool November night. Their pace is deliberate as they walk in a neat line from the back of the aging stronghold to its iconic facade. At the command of the event’s organizer, they stop, turn to face the fort and remove their hats as the organizer lays a wreath against the sandy brown brick. For the next minute, they stand in silence.

They’re marching for their past — as a tribute to the soldiers who fought and fell there in 1836 — but also for their future. The 13-day battle between a few hundred volunteer Texan soldiers and a thousands-strong Mexican army has come to symbolize the enduring notion central to the group: a steadfast resolve for an independent Texas nation.

Texas Nationalist Movement member Max Cruman, a current commercial pilot, talks about the movement after the monthly wreath laying on Nov. 9, 2019. He is one of the group’s 380,000 pledged supporters, according to the organization’s website. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas

The Texas Nationalist Movement, a peaceful advocacy group formed in 2005, is intensely critical of the federal government. Its central goal is fundamentally revolutionary: an economically, politically and culturally independent Texas. The group, a relatively recent addition to the state’s long history of secessionist movements, has had to grapple with skepticism and charges of racism. According to its website, the group has over 380,000 pledged supporters.

As the group’s coordinator for Bexar County, retired state employee Karl Gleim, 67, tallies attendees, choreographs the walk and is responsible for the wreath-laying. Gleim, a native of Virginia, professes a fierce allegiance to his adopted state. Nine years ago he pledged his support for Texas independence and, starting this year, took on the coordinator position.

“Washington, D.C., is the Titanic,” Gleim said. “It’s sinking by the head, and once it goes under, if we’re not sailing away in the lifeboat of Texas independence, we’re going to be dragged down with it — and I guarantee it won’t be a pretty sight.”

With the Texas flag hoisted in front of the group, Karl Gleim, second from left, and members of the Texas Nationalist Movement round the perimeter of the Alamo in San Antonio on Nov. 9, 2019. A native Virginian, Gleim professes allegiance to his adopted state and is now the group’s coordinator. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas

Gleim grew up in the northern Virginia suburbs, where he learned about the figures who framed and ratified the U.S. Constitution. When he moved to Texas in 1977, he realized that the defenders of the Alamo were as, if not more, patriotic than the founders.

“I view these guys as the same as Washington and Jefferson,” Gleim said. “They’re the founding fathers of Texas.”

Group members have the option of contributing financially. Alternatives include a recurring annual base membership fee of $30 or what’s known as the “1836 club,” where members pay $18.36 each month.

According to Daniel Miller, 46, president of the Texas Nationalist Movement, it has enjoyed a gradual uptick in support. “When we first started out, this idea of Texas independence, these conversations were had in hushed whispers in the backs of cafés in small Texas towns,” Miller said.

Members of the Texas Nationalist Movement tell a questioning visitor about the layout of the Alamo on Nov. 9, 2019. The group has seen a gradual increase in support and boasts an international outreach. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas

Now, similar conversations are held around the world. The Texas Nationalist Movement has an active international outreach. Members have spoken at self-governance conferences in France, London and Moscow. The group has friends in the Scottish National Party and ties to French and British Euro-skeptics, as well as parties in Catalonia, Miller said.

One of the marchers at the Alamo, Nate Smith, a technician for a mobile water and wastewater treatment company, said a thread connects the independence movements. “It’s a lot of the same frustrations, the same ideas,” Smith, who declined to give his age, said. “It’s the resistance to an encroachment on their freedom.”

Smith, who writes and performs songs about Texas self-governance, has spoken at independence conferences in France and Moscow.

Miller said the European groups “are seeking the same aims as we are, except where they live. There’s no doubt there is a global trend that spans pushing on a century now. It was important that we understand a lot better what this trend looks like.”

Texas Nationalist Movement member Pat Dwade, left, grips the Texas flag, as coordinator Karl Gleim marks down members’ names who joined the monthly event. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas.

Miller says the movement must overcome what Gene Sharp, late professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts, coined the principle of atomization: When a like-minded group feels isolated enough, members avoid speaking about certain topics for fear of retaliation or ostracization. Providing a space to talk openly and confidently about an independent Texas — transplanting those conversations from cafés to conference stages — is a sign, Miller says, that their efforts are working.

“Whenever our volunteers are out in the field doing outreach, maybe set up in a parking lot with flags and banners, it never fails,” Miller said. “Every time someone will drive past, whip their vehicle around, pull in and say ‘Where have you guys been? I’ve been looking for you my entire life.’”

Bexar County coordinator for the Texas Nationalist movement, Karl Gleim, stands in front of the Alamo after the monthly wreath laying in San Antonio on Nov. 9, 2019. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas

Texas has a long history of secession movements. After the Texas Republic ratified its constitution in 1836, it remained a nation for just over a decade before joining the U.S. in 1845. Despite the failed attempt at secession as a member of the Confederacy in 1861, the residue of a separatist mentality has persisted.

Member Pat Dwade looks onto the Alamo Cenotaph monument in San Antonio on Nov. 9, 2019. The monument was erected in memory of those who died in the battle on March 6, 1836. Some see secession movements as embodying racists beliefs, said University of Texas history professor Walter Buenger. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas

In its infamous 1997 manifestation, Republic of Texas leader Rick McLaren held two people hostage in Fort Stockton in a seven-day armed standoff with law enforcement. Miller stresses that the Texas Nationalist Movement has no affiliation with its predecessor. “First of all, it’s a peaceful movement,” Miller said. “So it’s not going to be done without a vote of the people.”

One attendee at the Alamo march, who preferred to remain anonymous, said he had been a member of the group for eight years and a supporter of independence for much longer.

The culture of Texas is unique, he said. “It’s freedom, it’s family, it’s God,” he said, his face cast in shadow by his cowboy hat’s wide brim. “It’s fighting for what’s right; it’s tough. All these things (that) made Texas unique and prosperous, they’ve been scraped away, denigrated, assaulted — and it’s shriveling as fast as can be.”

Walter Buenger, professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, said secession movements in Texas often embody, in some form or fashion, racist beliefs.

“Oftentimes when people talk about one unified Texas culture, they’re talking about Big Tex at the State Fair: a larger-than-life white male cowboy,” Buenger said. “They’re not talking about reality, they’re talking about myth.”

Miller vehemently condemns this claim. He called the white nationalist implications “a tired and worn-out slur against Texans of all ethnic backgrounds that support the TNM and an independent Texas.”

Grappling with these racialized accusations, Miller said, is not new for the group. This session, Texas state Sen. José Rodríguez, D-El Paso, called the group a “white nationalist movement” on the senate floor. “We are not unused to hearing this type of ignorance,” Miller said.

Miller asserts that the group’s demographics would surprise critics who assume the movement comprises primarily older, Republican men. He said the movement mirrors the demographics of the entire state better than either major political party, based on the results of occasional surveys. However, Miller did not provide data to verify this claim.

When Barrack Obama was elected in 2008, Buenger said, Texas saw an upsurge in secessionist activity with what he called racist overtones.

Miller said the Texas Nationalist Movement did see an uptick in membership in 2009 but that after the election of President Trump, declared support increased by 159%.

As tourists take photographs, members of the Texas Nationalist movement march to the front of the Alamo in San Antonio on Nov 9, 2019. Support for the movement has increased 159% since Donald Trump was elected president, according to Daniel Miller, the movement’s president. Alexander Thompson/Reporting Texas

“Everybody’s fixated on Republican vs. Democrat, Trump vs. Pelosi,” Miller said. “But the real fight that’s been going on here all along is this increasing gap between Texans who just want to govern themselves, and people who want to continue to push power into the federal government and override the will of the Texan people.”