As Hemp Bill Nears Passage, Expert Warns of Potential Pitfalls

By MIchael Minasi

Reporting Texas

The leaves of a cannabis plant—grown for medical CBD oil—are pictured on Tuesday, April 23, 2019, at Compassionate Cultivation in Manchaca, Texas. Michael Minasi/Reporting Texas

The Legislature seems on the verge of making hemp farming legal, pleasing agricultural interests, but a plant scientist cautions that successful cultivation and marketing of Texas hemp is no sure thing.

The Hemp Farming Act, or House Bill 1325, passed the Senate unanimously on May 16. Once the Senate and House hash out the differences between their versions of the bill, it will head to the desk of Gov. Greg Abbott.

HB 1325 would make it legal to produce, process and sell hemp products in Texas for the first time since hemp’s prohibition in 1970, when the Controlled Substances Act was written into law.

Since Congress legalized industrial hemp at the end of last year, the number of states that have created regulations for growing hemp has grown to 42. Texas farmers hope to get a piece of the $3.7 billion global hemp market, but they should not be too quick to start growing. Even if the governor signs off, hemp will not be legal to grow until the state agriculture department develops regulations for the industry, and then the U.S. Department of Agriculture must approve the plan. Despite common rhetoric about hemp’s uses, value, and hardy, drought-resistant nature, some experts are voicing concerns that the challenges of raising and selling hemp profitably are being glossed over.

A cannabis plant—grown for medical CBD oil—is pictured on Tuesday, April 23, 2019, at Compassionate Cultivation in Manchaca, Texas. Michael Minasi/Reporting Texas

“I’m not so sure that it’s a bad thing that we’re this far behind on industrial hemp because a lot of times when these things start up, it doesn’t work out. A farmer grows a hundred acres of hemp and something changes — maybe the market he thought he had didn’t materialize or wasn’t sustainable,” said Calvin Trostle, a Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service agronomist and professor.

Advocates celebrate the many uses for hemp — its fibers can be used for everything from textiles to construction materials, and hemp derivative CBD oil is lauded for many medical and wellness treatments from seizures to anxiety.

“This is all about taking the shackles off the American farmer,” Agricultural Commissioner Sid Miller said in a statement last year. “It is time to finally end the ban on industrial hemp and free Texas farmers to produce this valuable commodity.”

Hemp is a type of cannabis. At first glance, it might be mistaken for its psychoactive cousin, marijuana, but hemp is a completely different strain of cannabis with different physical and chemical characteristics. Hemp is naturally low in tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive ingredient that gets marijuana users high, and high in cannabidiol (CBD), the component proven to help with epilepsy. Under U.S. law, hemp plants must register less than 0.3 percent THC, whereas marijuana strains often have concentrations of THC up to 35 percent.

Mike Rubin, Compassionate Cultivation’s Vice President of Business Development, speaks about the cannabis production process on Tuesday, April 23, 2019, at Compassionate Cultivation in Manchaca, Texas. Michael Minasi/Reporting Texas

The only currently legal cannabis plants in Texas are grown in three licensed facilities through the Texas Compassionate Use Act of 2015. The largest of those three is Compassionate Cultivation, which produces CBD oils and sprays solely for patients diagnosed with intractable epilepsy. The business controls every stage of CBD oil development, from the seed to hand-delivering products to customers across the entire state. Its facility in Manchaca, just south of Austin, is more reminiscent of a biotech firm than a farm. Plants grow indoors under meticulously monitored and controlled lighting and watering conditions. Advanced processing and testing equipment checks for pollutants, anomalies and proper THC and CBD levels.

It’s a far cry from the rocky, drought- and heat-resistant settings championed by hemp farming advocates.

“We think it’s important that the hemp industry is regulated properly and that those products that are intended for human consumption are safe and meet all the assurance and quality control standards in order to ensure the health and the safety of those Texans that are taking those products,” said Mike Rubin, Compassionate Cultivation vice president of business development. “One of the things we like to say is CBD is medicine and as such, it needs to be managed like any other medicine.”

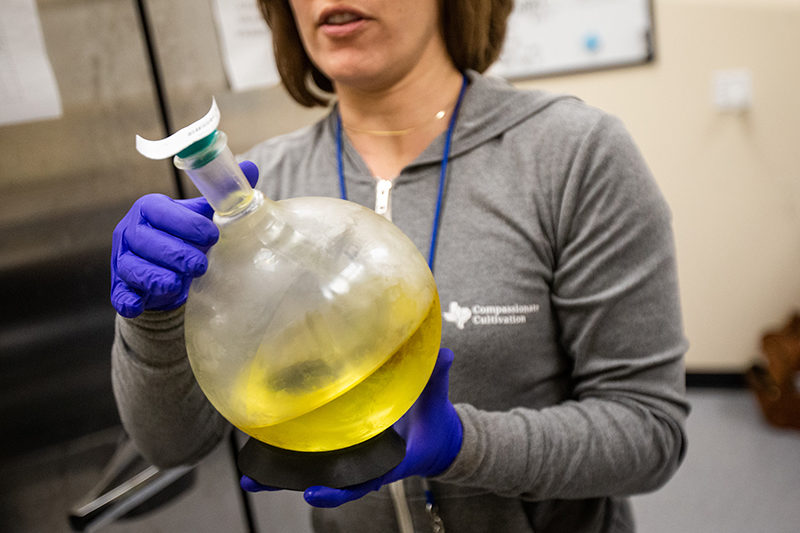

A Compassionate Cultivation employee displays a batch of frozen CBD oil during the production process on Tuesday, April 23, 2019, at Compassionate Cultivation in Manchaca, Texas. Michael Minasi/Reporting Texas

Growing the crop for industrial use could be more forgiving, but at the beginning, growers would rely mostly on guesswork. There have been no studies at Texas A&M University on the best growing practices for hemp in Texas due to its illegal status.

Trostle is based in cotton growing country — Lubbock — and specializes in alternative crops like those that combat climate-change effects like drought and heat, but he cautions that established academic literature on the ideal environments for hemp is divided.

“I read that some think that you need to grow industrial hemp where your annual rainfall is 25 inches or more. So that eliminates all of the High Plains – draw a line from about Vernon to Abilene and to probably Laredo, and then everything west of that line would be less than 25 inches,” Trostle said.

A room of cannabis plants—grown for medical CBD oil—is pictured on Tuesday, April 23, 2019, at Compassionate Cultivation in Manchaca, Texas.

That means hemp farming might require irrigation in West Texas, and water is expensive there.

Even if farmers are able to grow industrial hemp efficiently, they also need to establish markets for their products — globally, China and Canada hold a significant lead over the U.S. in hemp cultivation.

“I guess in some ways as we watch other states with their various programs and various stages of development we’ll see how things progress and then maybe folks in Texas that move into this market themselves will learn from what they’ve seen in other states and avoid potential pitfalls,” Trostle said.