UT’s Graduation Rate Gender Gap: Women Do Better than Men

By Lucy White

Reporting Texas

UT students walk to class along the Main Mall in front of the bell tower on Oct. 17, 2018. Salvador Castro/Reporting Texas.

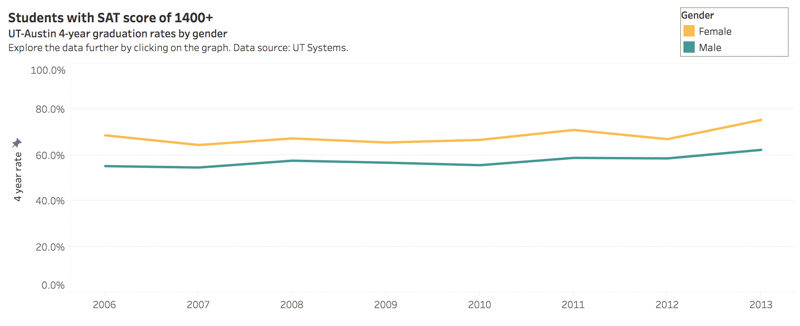

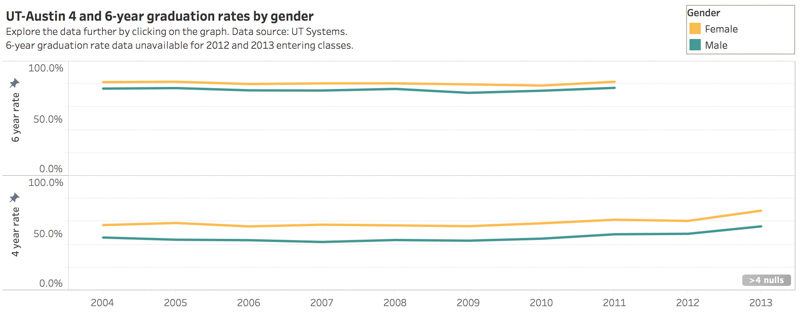

Men are falling behind their female peers in graduation rates at the University of Texas at Austin. The difference in four-year graduation rates between males and females is often 10 percentage points or more. In 2017, 70 percent of women graduated in four years while only 56 percent of men did.

The university recently concluded a five-year initiative to improve four-year graduation rates among both men and women — the goal was to reach a 70 percent on-time graduation rate by 2017. Among women, the university met its goal. It failed among men.

A graduation rate task force produced a progress report detailing successful initiatives that encourage undergraduates to finish in four years. The report did not address the fact that the most consistent predictive indicator of a student’s ability to graduate on time is gender.

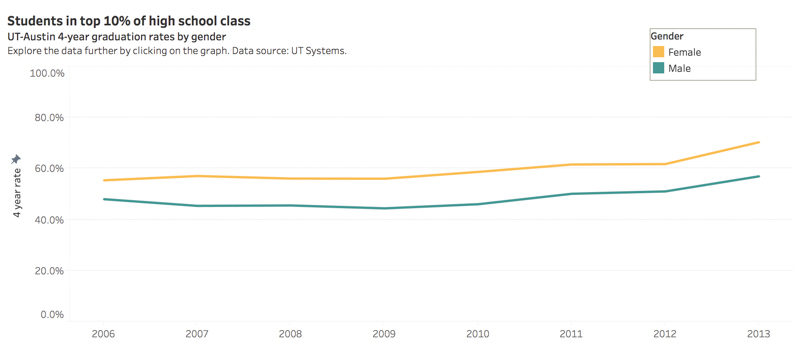

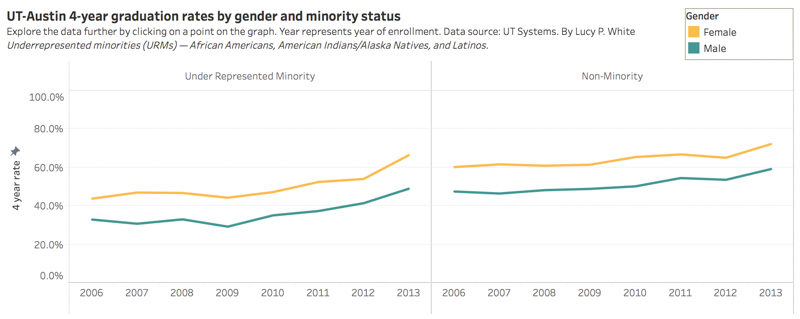

These findings are the result of a Reporting Texas analysis of data obtained with a public information request to the University of Texas System for UT-Austin undergraduate graduation rate information by gender, SAT score, class rank and race. The data covers incoming classes from 2004 to 2013, and it shows a gap between men and women in every year and category.

Women continue to outperform their male peers even while overall graduation rates improve. While many educators and officials are aware that some male students are struggling, there are few formal efforts underway to change the situation. A university press release this fall highlighted record-high graduation rates for the class of 2018 but did not address the gender disparity.

Click on any graph to explore graduation rate data further. Or click here.

“Beginning in elementary school, we socialize girls and young women to be rule-followers and meet expectations of people in authority,” said Catherine Riegle-Crumb, associate professor of education at UT-Austin. Her research focuses on gender and racial inequalities in educational experience.

According to Riegle-Crumb, gender differences all are related to social norms: “We raise boys to be independent, not [defer] to authority.” She argues that some of the confidence that comes from such independence can have unanticipated consequences at college — women who spent years building study habits have an advantage over men who were given more freedom at a younger age.

Riegle-Crumb believes this can result in men being “late bloomers” who take a few more years to build the skills necessary to succeed in college. That might explain why the gender gap shrinks when comparing six-year graduation rates. Seventy-seven percent of men who enrolled in 2011 graduated in six years, compared with 82 percent of women.

Click on any graph to explore graduation rate data further. Or click here.

UT-Austin mirrors a national trend. Before 1982, men had higher college completion rates than women did. In 1982 the trend flipped, and it has increasingly favored women ever since. By 2025, about 58 percent of bachelor’s degrees in the U.S. will go to women, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Asking for help

UT-Austin’s graduation task force implemented several strategies to improve overall rates. It made freshman orientation mandatory, so that every student could arrive feeling better acclimated to campus. Students now are frequently reminded of their four-year graduation target; admission offer packets even feature a class-year logo. According to the task force report, “This was the first time at UT-Austin that it was communicated to students that there is an expectation for them to graduate in four years.”

The task force paid extra attention to low-income students. The university now uses predictive analytics based on certain demographic data to identify students who might need extra help from day one. UT-Austin reported significant gains in graduation rates for Pell Grant recipients, first-generation college students, blacks and Hispanics.

“We’ve paid special attention to groups whose historical attainment levels have not matched the university average overall,” said Cassandre Giguere Alvarado, director of student success and graduation initiatives at UT-Austin.

Men have lower graduation rates regardless of race. Though there is an overall gap between minority and non-minority students, the gender gap remains within groups. Graduation rates among female minority students have surpassed graduation rates among non-minority males according to the two most recent years of data. Sixty-six percent of minority women who enrolled in 2013 earned a degree in four years; 52 percent of non-minority male students graduated in the same time.

Click on any graph to explore graduation rate data further. Or click here.

“The rates between men and women are not a surprise to me,” Alvarado said. Still, the university has no specific plan to address the overall gender disparity in graduation rates.

“I understand this data shows females outperforming males, and that is important information,” said Joey Williams, director of communication for UT-Austin. “But we’re most interested in focusing our resources on helping all students, and in particular the students that need the help the most, and for many students, affordability issues are the biggest barrier to graduation,”

Alvarado said that university mentorship programs “will continue to be an area of focus moving forward.” The university has a range of mentoring programs geared toward both genders — from freshman orientation to programs in individual colleges.

Project MALES (Mentoring to Achieve Latino Educational Success) sends UT-Austin students, men and women, to local middle and high schools to mentor Latino boys for academic success. Mentors themselves can gain from the program, said Mike Gutierrez, program coordinator for Project MALES: “Students doing the mentoring need to hold themselves and each other accountable. You can’t tell someone else to do it unless you’re accountable.”

Tellez leads the Project MALES group in a discussion on Oct. 15, 2018. Salvador Castro/Reporting Texas.

Gutierrez said a similar program could work for male mentees who attend UT-Austin. But getting men to participate can be challenging.

“Males haven’t figured out that they need help. They are afraid to admit that they need help,” said Susan Harkins, assistant dean at the College of Natural Sciences. Harkins runs the TIP Program, an academic community for first-year students in the college that includes mentoring and advising help. The university’s predictive analytics identify TIP scholars before they arrive. Many are low-income, minority or first-generation college students.

TIP began as a voluntary program. The college invited students to join through a letter that stressed the importance of community and belonging. Women responded overwhelmingly to the letter, but few men replied.

The college reconsidered its audience and stressed different, more tangible TIP benefits to attract more men.

“We had to rewrite the letter, and we used to joke that it was a ‘get stuff’ letter: you will get a higher GPA,” said David Laude, a UT chemistry professor who started TIP. In his own 500-student general chemistry section, he said, he sees male students struggling to ask for help, even though he has scheduled office hours when students can get help, one on one.

“If I hold an office hour, it is not unusual for me to have 40 women and no men to show up … I mean, it’s striking.”

Laude holds extra office hours to review material before exams. He used to hold the sessions on Sunday nights until he saw that roughly 95 percent of the students who came were female. He realized that he was competing with Sunday night football. “I actually had to move office-hour time for men to show up,” Laude said.

A male student who is struggling tends to wait longer to ask for help than female peers do, Laude said. By then, Laude said, it is sometimes too late to catch up before an exam.

Feminization of education

The Texas Legislature has focused on increasing the number of college graduates statewide through the 60x30TX Higher Education Plan. The plan aims “for 60 percent of the 25- to 34-year-old Texas population to hold a certificate or degree by 2030,” according to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board website.

The coordinating board is aware of the gender gap in degree attainment. “We know that’s a problem, and we’re working on it right now,” said Raymund Paredes, commissioner of higher education. But he acknowledged, “I don’t think we know what all the answers are.”

Paredes said part of the problem is the lack of longitudinal data on successful initiatives for male students. Replicating successful programs from a particular school can be difficult because officials do not know what is scalable, he said.

Some mentorship programs might not reach male students through formal initiatives, but because of an individual’s unique approach. Harkins makes sure that all TIP promotional materials include photos with men, even though the College of Natural Sciences is majority female and many pictures only include women. She seeks out male mentors to work at the reception desk: “I go out and beat the bushes for men because I want them role-modeling. I want males to see a male behind a desk and know it’s okay to do that.”

Armando Tellez, a graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin, instructs Project MALES on Oct. 15, 2018. Salvador Castro/Reporting Texas.

Paredes said addressing men’s needs is a challenge at a time when women still face gender barriers. He said he has received criticism from women for saying that men require some targeted support.

Laude helped create the first version of the university’s predictive analytics tool and was senior vice provost for enrollment and graduation management. He said that because of legal concerns, the university prevented his team from including race or gender as a predictive indicator.

Still, something is preventing UT-Austin men from reaching parity with women. “Males don’t do as well in school as they could and should,” Paredes said. “Some people claim male youth culture doesn’t esteem academic success.”

“Most things that are female-dominated have lower social status,” Riegle-Crumb said. She thinks that as the graduation trends continue, education is becoming feminized and, possibly, less attractive to young men.

Diego Macias was a TIP mentor and will join Teach for America after graduation. He echoed Riegle-Crumb: “Education is feminized, and it’s like, why? Education shouldn’t have a gender. Everybody needs to be educated.”

Macias, a Human Development and Family Sciences major, said he can count on one hand the number of men in his classes. “When I switched to this from neuroscience, my parents weren’t super thrilled by it, and I think it’s hard for males to feel comfortable making a decision like that,” Macias said.

If a male student is struggling or lacks passion for his studies and also is low-income or the first in his family to attend college, he may get “survivor’s guilt,” both Gutierrez and Macias said. He may feel he could support his family better by working than going into debt for school. “They get comfortable earning a certain income, and then they don’t want to go back,” Macias said.