UT System’s Los Alamos Lab Bid Promises Prestige But Also Challenges

By Scott Squires

Photography By Scott Squires

Reporting Texas

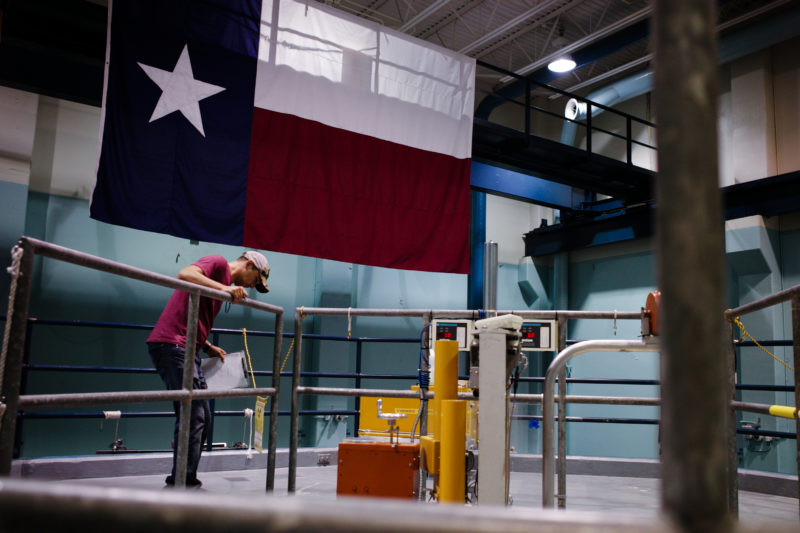

Matt Stokely, a graduate student at the University of Texas studying nuclear and radiation engineering, prepares the Nuclear Engineering Teaching Lab’s research reactor for operation. Scott Squires/Reporting Texas

In a nondescript building in North Austin, Mike Whaley punches illuminated buttons on an analog control panel. A large monitor above the console displays green bars that inch higher, indicating the growing intensity of the nuclear fission reaction occurring in the next room.

“Increasing power to 900 kilowatts,” Whaley announces into a microphone on the desk.

Whaley is assistant director of the Nuclear Engineering Teaching Lab, the nuclear research reactor and laboratory at the University of Texas’ J.J. Pickle Research Campus.

The reactor produces radiation for experiments such as neutron activation analysis and nuclear forensics, used to detect illegal nuclear weapons testing.

That work could be boosted significantly, if UT’s ambitions to expand its nuclear profile beyond research succeed. In September, the University of Texas System approved spending up to $4.5 million on a bid to manage Los Alamos National Laboratories, the legendary facility in New Mexico that in the 1940s developed what physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer called “the destroyer of worlds” — the atomic bomb.

Los Alamos, near Santa Fe, is the nucleus of the U.S. atomic weapons program. The lab manufactures bomb components such as plutonium pits — the grapefruit-sized hemispheres of radioactive metal that give nuclear weapons their annihilative power.

It also conducts advanced research into a wide range of fields related to nuclear defense and deterrence, including detection of illegally trafficked nuclear weapons and the development of materials that can withstand extreme conditions. The lab’s work includes research in fields related to national security, such as clean energy and bioscience.

Mike Whaley powers up the reactor at UT’s Nuclear Engineering Teaching Lab. Constructed in 1992 by General Atomics, it is the most recently built reactor in the U.S. Scott Squires/Reporting Texas.

If the UT System wins the contract, the university could benefit from what experts say could be tens of millions of dollars in additional research opportunities. A successful bid to manage the lab would position UT as part of the U.S. national security apparatus.

But the UT System has some high-powered rivals, including Texas A&M University, whose regents voted Oct. 19 to pursue the contract, the University of New Mexico and possibly other institutions.

Whoever wins the job would win considerable prestige but also inherit some headaches.

For years, Los Alamos has been plagued by high-profile missteps. In 2011, scientists shirked safety protocols by collecting highly reactive plutonium rods for display in a photo-op. The lab has also been cited for the improper shipment and disposal of radioactive waste, and public breaches of classified information. In September, Director Charles McMillan abruptly said he would resign by year’s end.

So why would the UT System want to inherit a lab that has been dogged by safety and security issues of nuclear proportions?

“Ultimately, it’s in the national interest,” said David Daniel, the system’s deputy chancellor. “This is an opportunity to bring our people and our know-how to Los Alamos, and at the same time, to serve the nation.”

Questions about the nation’s nuclear capabilities are particularly urgent, now that President Donald Trump has expressed an interest in vastly increasing America’s nuclear arsenal, even as he continues his fire-breathing rhetoric against North Korea and its nuclear hubris.

Whether or not the U.S. eventually increases its arsenal — international treaties cap the U.S.’s stockpile at around 4,000 nukes — plans to modernize the nation’s nuclear weapons are already in early stages. President Barack Obama committed the United States to upgrade and modernize its arsenal, which could cost up to $1 trillion over the next three decades.

But managing the lab will involve research that goes far beyond the nuclear arsenal.

“There’s lots of other projects going on other than just weapons research,” said former Los Alamos employee Erich Schneider, now a UT-Austin nuclear engineering professor. The lab focuses on everything from materials science and fluid mechanics to biological and environmental science research.

“There’s a cross-disciplinary interchange at the lab,” Daniel said. “This is how synergism works.”

Cherenkov Radiation is the blue glow that emits from the core of the reactor during nuclear fission. It is like a “sonic boom,” but with light instead of sound. Scott Squires/Reporting Texas

If the UT System wins the bid, it would manage all aspects of the lab’s day to day operation including personnel, equipment and services for five years, at which point it can renew the contract for another five. The lab has 11,200 employees.

The System made a failed bid to operate Los Alamos in partnership with Lockheed Martin in 2005. The System also teamed with Texas A&M in 2016 in an effort to run Sandia National Labs, another Department of Energy facility that manufactures the non-nuclear components of U.S. weapons.

The University of California System ran Los Alamos in its early days of designing and testing nuclear weapons, and all through the Cold War. But it almost lost the contract in 2003 when two workers inhaled plutonium after a sudden chemical reaction. Following that incident, the Department of Energy announced it would for the first time place management at Los Alamos up for bid. UT jumped at the chance, but UC hung on by joining forces with a team of managers from the private sector.

That riled engineers and policy experts, who warned the lab’s problems would only continue. They were right.

“They had their problems, they spent a bunch more money, and they still had the same problems,” said Scott Kovac, operations and research director at Nuke Watch, a nuclear weapons watchdog group in New Mexico. “Privatization of the contracts has not seemed to help at all.”

In 2015, a year after an improperly packaged drum of waste from Los Alamos burst at a New Mexican disposal site, the Department of Energy opted not to renew the private consortium’s contract. Now, the National Nuclear Security Administration, the DOE agency that manages the bid, is looking for a new manager. In its draft request for proposals, the NNSA said it is looking for a contractor to implement a “culture change,” and operate the lab with fewer safety incidents.

“Whoever gets the contract, in NNSA’s opinion, is whoever has the most experience dealing with these huge projects, and for the least amount of profit,” Kovac said. The agency is evaluating possible contractors on past performance, key personnel, small-business participation and cost, according to the proposal.

Now, the UT System sees an opportunity to reclaim Los Alamos’ legacy of academic leadership.

“We know how to run these big complex organizations, and we believe that the best way to instill a culture of responsibility is to have a single entity directing operations at the lab,” Daniel said. “We don’t want to run the lab by committee, we want to run it like a campus.”

Unlike its last attempt, the UT System is the driving force behind the bid. But it will seek partners, and who they are could matter greatly in whether its bid succeeds. Although the UT System declined to say who those partners might be, other entities that could join ranks or emerge as rivals include General Dynamics and MAG Aerospace, as well as the University of California System and Bechtel, one of UC’s partners currently running the lab.

But Daniel says that the UT System can offer something that its private-sector opponents can’t: when the lab faces challenges, it can reach into its massive organization — its eight universities, six health institutions, and almost 90,000 faculty and staff — to find experts.

Unlike the lab’s current management, they have a “superb track record,” Daniel said. “It’s about taking responsibility and having an understanding that leaders have to be held accountable.”

Former Texas Gov, Rick Perry is now secretary of the Department of Energy, but whether that will be a factor is hard to tell; Perry is an A&M alumnus. The UT System played down the Perry angle.

Running the lab could steer big research dollars to Austin, but a change in who’s in charge could come even sooner, and with a direct impact on UT’s teaching lab.

When Los Alamos was cited in June for improperly transporting nuclear materials, the lab shut down all shipments to its partners across the country — including the UT teaching lab — until it could examine its safety protocols.

“It’s a problem,” NETL Manager Tracy Tipping said. “Since Los Alamos can’t ship anything, we can’t get our stuff.”

Fixing that should be priority, Tipping said. “Regardless of who wins the bid, that’s at the top of the list. We need to get this addressed.”

Whaley said that won’t be easy.

“A large organization like a national lab has a lot of inertia,” he said.

Beyond solving those immediate issues, he said a new manager at Los Alamos might not mean that much for the day-to-day operation at the UT teaching lab. But Tipping predicted a successful bid could mean lots of opportunity for UT’s research community.

“There’s a lot of dollars at stake here,” Tipping said. Los Alamos operates on a yearly budget of around $2.5 billion. Between five and seven percent of that budget — up to $175 million — is allocated for lab-directed research and development projects.

That means that if the UT System ran the lab, it would be easier to set up contracts for UT graduate and faculty research, as well as internships and job opportunities.

The UT System would have other opportunities to profit from Los Alamos. Past management and operations contractors have collected royalties that have totaled as much as $100 million, according to Kovac. The NNSA also grants the managing contractor a yearly award fee — almost $60 million in 2016 — if the lab reaches its yearly goals.

“There’s a pile of money here that the laboratory would get to deal out to whoever they want,” Kovac said. That could mean big bucks for the UT System.

Although the formal call for proposals has not been issued yet, the Department of Energy will start the bidding process, “any day now,” Daniel said. “We’re in a very busy mode, but we’re prepared to drop everything.”