Universities Fear Trump Policies Driving Away Iranian Students

By Dani Neuharth-Keusch

Reporting Texas

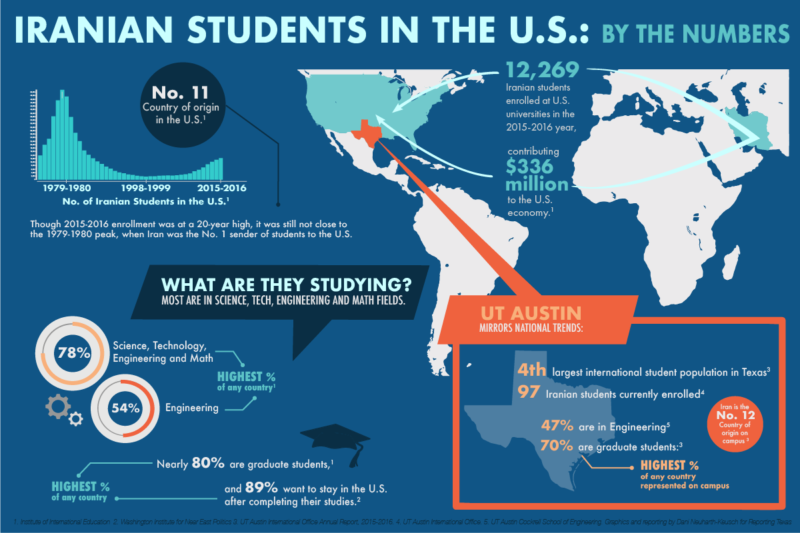

The majority of international students studying in the U.S. who could be affected by President Donald Trump’s shifting immigration and visa policies are from Iran. The 12,269 Iranian students enrolled at U.S. universities in the 2015 to 2016 academic year contributed hundreds of millions to the economy, and mostly study at the graduate level in science, technology, engineering and math fields. Data: Institute of International Education, Washington Institute for Near East Politics, World Education Service and University of Texas. Graphic: Dani Neuharth-Keusch / Reporting Texas

Shifting federal visa policies have left more than 12,000 Iranian students in the United States in limbo. Federal judges halted the latest version of President Donald Trump’s executive order restricting travel from six Muslim-majority countries within days of its issuance last month, but researchers and universities worry that political uncertainty will drive Iranian talent elsewhere.

At the University of Texas at Austin and across the U.S., Iranian students are by far the largest population of foreign-born students and scholars who would be impacted by Trump’s executive order, which a Maryland judge interpreted as a “Muslim ban.” An earlier version of the ban, issued Jan. 27, was overturned by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Still, the administration has pledged to continue fighting court injunctions and to reintroduce a version of the ban that will withstand legal challenges. This shaky political landscape has fueled uncertainty about the future of Iranian students in the U.S.

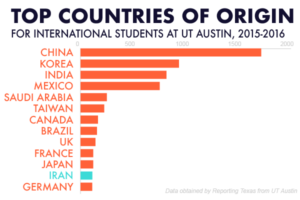

Iran ranked 12th among the countries of origin for international students at UT-Austin in 2015-16. Of the 110 current students and scholars from the countries covered by the original executive order, 97 are Iranian, according to data obtained by Reporting Texas. Almost all are graduate students — 46 of them at the Cockrell School of Engineering.

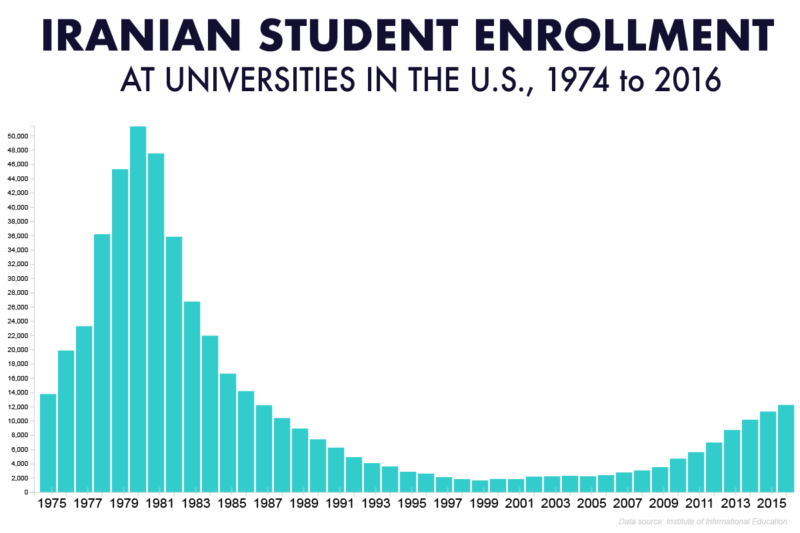

The numbers at UT mirror national trends: Iran was the 11th most popular country of origin for international students in the U.S. in 2016. More than 12,000 Iranian students enrolled at American universities in the 2015-16 academic year — the highest number since 1979 to 1980, when Iran was the top exporter of foreign students into the United States. Of those, nearly 78 percent studied at the graduate level, the highest proportion of any country, according to data from the Institute of International Education.

“Students have certainly been impacted by shifting policies, which has been difficult,” Teri Albrecht, the director of International Student and Scholar Services at UT-Austin, said in an email.

Iran is the 12th most popular country of origin for international students at UT Austin, where 6,069 international students were enrolled last year. This is slightly below the national average, where Iran ranked 11th among all countries of origin. Data: The University of Texas at Austin International Office. Graphic: Dani Neuharth-Keusch / Reporting Texas

The revised March 6 order gives Customs and Border Protection more latitude to issue exemptions and waivers in certain cases — allowing returning students who hold a visa, for instance. But these waivers are discretionary and do little to quell uncertainty.

“All of our international students — Iranian students included — bring a diversity of thought and perspective, which often leads to new and creative ideas,” said Patrick Wiseman, the Cockrell school’s communications director. “New solutions to societal challenges cannot be discovered without new ideas.”

Wiseman also said that changes to the U.S. H-1B visa program, which Trump has pledged to target, could affect graduate student enrollment and faculty hiring. Of the 31 Iranian scholars enrolled at UT-Austin in the 2015-16 academic year, 19 had H-1B visas.

“We have many outstanding faculty who first held H-1B visas and are not U.S. citizens,” Wiseman said. “They have brought their talents to our country, helped develop innovations that advance society and helped educate generations of successful engineers.”

The engineering school is in the middle of admissions and recruitment for graduate students, who have until mid-April to decide on offers of admission. The school won’t know if those numbers have substantially changed until after the process concludes May 1.

Preliminary data from the Institute of International Education show that nearly 40 percent of 250 U.S. colleges and universities polled report a drop in international student applications, particularly among students from Middle Eastern countries.

In the same vein, a February report by World Education Services projected that applications will decline as Iranian students pursue offers from universities in “more welcoming” countries.

Those losses could add up.

The Institute of International Education estimates that in 2016 alone, Iranian students enrolled at U.S. universities contributed $386 million to the nation’s economy. Nationwide, the 1 million international students in the U.S. account for $36 billion. The 82,000 international students in Texas, the third most popular destination after California and New York, contribute more than $1.9 billion to the state, the group reported.

“There would certainly be economic impact if the enrollments start to decline,” Sharon Witherell, the group’s director of public affairs, said in an email.

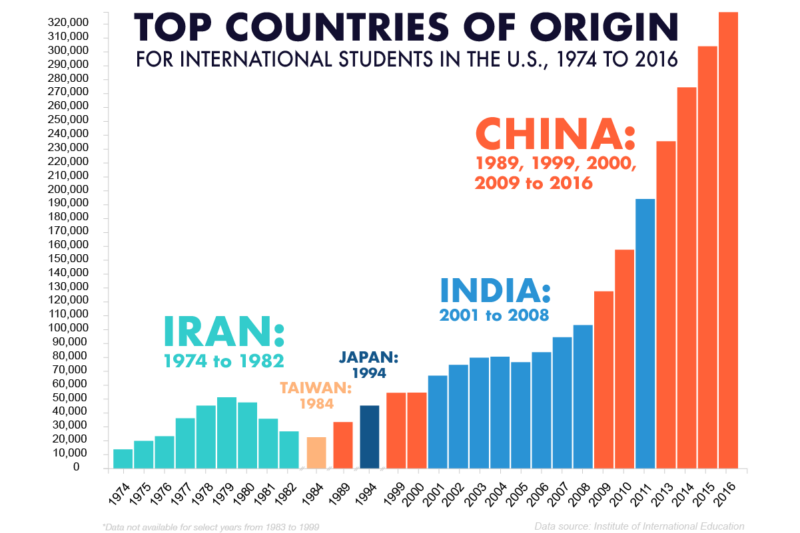

Iran was the top sender of international students to the U.S. from 1974 to 1982. Enrollment began falling following the 1979 Iranian Revolution and bottomed out in 1998-1999. It has been rising steadily since, and 2015-2016 was the highest enrollment in 25 years. Data: Institute of International Education. Graphic: Dani Neuharth-Keusch / Reporting Texas

More Iranians call the United States home than any other country outside of Iran. Iranian-Americans are also among the most educated ethnic groups in the U.S., topping the list among 67 ethnic groups surveyed in the 2004 Census, according to the World Education Services report.

Since the early 2000s, Iran has invested significantly in education. Total national enrollment in higher education was just over 19 percent in 1999, compared with nearly 72 percent in 2015 — twice the global average, World Education Services found.

But as the number of qualified job seekers in Iran has grown, so has youth unemployment, hitting 29 percent in 2014. There are also demographic drivers: more than 60 percent of Iran’s population is under the age of 30, according to World Education Services.

Political repression in Iran also plays a role. A 2016 report from the U.S. Department of Justice ranks the country “not free,” with two out of 16 possible points for “freedom of expression and belief.”

The upshot: Many young, college-educated Iranians are leaving the country.

“Young Iranians increasingly seek international education as their sole means to experience the broader world, pursue economic opportunity and escape social and political repression in Iran,” Steven Ditto wrote in a 2014 report for the Washington Institute for Near East Politics.

Morad Ghorban, director of government relations and policy for the Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans in Washington, said demand for U.S. education is high among Iranian students, who by the same token are in high demand by U.S. institutions.

“The U.S. has one of the best post-secondary and graduate education systems in the world,” he said. “Iranian students, like others, want to study in the best institutions. In fact, many of the Iranian students come from good technical universities in Iran and are coveted by institutions such as Stanford and MIT because of their brilliance.”

The vast majority of Iranian students in the U.S. also want to emigrate here. According to a 2014 report by the Washington Institute for Near East Politics, nine in 10 Iranians studying in the U.S. said they intend to pursue permanent residency after completing their studies — the highest percentage of any country.

Trends in migration and enrollment at U.S. universities have fluctuated over time and are susceptible to politics.

In 1979, amid the Iranian hostage crisis, President Jimmy Carter issued a temporary visa ban for Iranians and ordered Iranian students in the U.S. to report to immigration authorities. Iranian student enrollment fell sharply in the years that followed, and the 2016 peak was still only half of 1979 levels.

Iran was the top sender of international students to the U.S. from 1974 to 1982. Enrollment began falling following the 1979 Iranian Revolution and bottomed out in 1998-1999. It has been rising steadily since, and 2015-2016 was the highest enrollment in 25 years. Data: Institute of International Education. Graphic: Dani Neuharth-Keusch / Reporting Texas

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s election in 2013 renewed hopes for international cooperation and diplomacy. In 2015, the Institute of International Education launched the Iran Higher Education Initiative, a program aimed at fostering engagement between U.S. and Iranian universities in response to Rouhani’s call for “increased international cooperation between higher education institutions in Iran and abroad, including the United States.”

“It had been the policy of the Obama administration to encourage Iranian students to come to the U.S. for their education,” Ghorban said.

But with the Trump era comes uncertainty.

“With the travel ban executive order, President Trump has sent a different message,” Ghorban said. “I have heard stories of how the ban has disrupted prospective students from applying to universities in the U.S. and has left many students currently studying in the U.S. in limbo.”