Felons Face Difficulties in Regaining Voting Rights

By Molly Smith

Reporting Texas

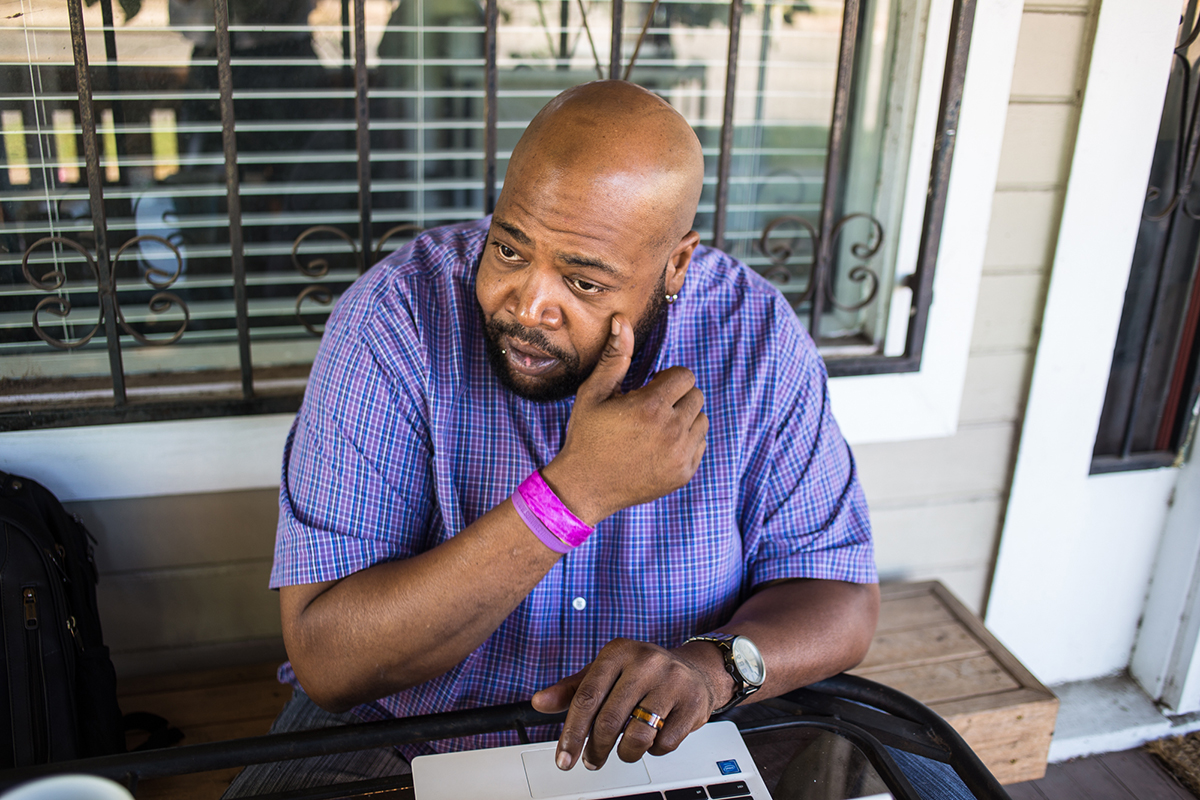

Lewis Conway, a former felon, now helps others with their criminal justice issues. He works with Grassroots Leadership, based in East Austin. Sifka Etlar/Reporting Texas

For Reporting Texas

The last time Lewis Conway Jr. voted was in 1992, when he cast his ballot for Bill Clinton. This November, he will head to the polls for the first time in more than two decades.

Conway, 46, hasn’t lacked interest in voting. Rather, a voluntary manslaughter conviction from 1992 barred him from voting until he completed parole, which came to an end in February 2012.

This election season, 6.1 million American adults will be unable to vote because they have been convicted of a felony, according to The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit organization focused on criminal justice reform. That number translates to one of 40 people nationwide.

Felony disenfranchisement laws vary by state, and Texas does not restore felons’ voting rights until they have completed parole and/or probation, a process that can take years, if not decades. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) reports that 389,000 people were barred from voting as of October 2016.

As a result, 2.5 percent of voting-age Texans cannot vote, noted a recent report from The Sentencing Project. Southern states had the highest rates of felony disenfranchisement, with Florida at 10.4 percent, Mississippi at 9.6, Kentucky at 9.1 and Tennessee at 8.3.

Conway had no idea he could register to vote until last spring, when he became involved in criminal justice advocacy work in Austin. He is a criminal justice programs associate at Grassroots Leadership, an Austin-based nonprofit that works to end for-profit incarceration in Texas.

Although there are no data on the number of former felons who have registered to vote, felons likely represent one of the largest groups of unregistered voters. Conway estimated that 80 percent of formerly incarcerated people he talks to in Austin do not know they can register after completing parole, and even when they do, they don’t know when that will be.

For the 70,000 men and women TDCJ releases annually, finding out when they can register to vote is often the furthest thing from their mind.

“The immediate concern coming out of prison is not going back to prison,” Conway said. “There are certain obstacles that immediately are presented to you where you can’t see voting as being important.”

His first priority upon his release on parole in 2000 was finding a job, since securing employment is a condition of parole in Texas.

Felons have also been overlooked by nonprofit organizations that work to register eligible voters across the state.

Steve Huerta saw this first hand at voter registration events in San Antonio. Huerta is president of the San Antonio chapter of All of Us or None, a grass-roots organization that works to advance the political rights of currently and formerly incarcerated people.

“Grass-roots organizations and community organizations don’t target our population because they don’t know we can vote. When I tell them I’m a convicted felon they tell me, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, you can’t vote’,” he said.

Conway said the organizations he works with in Austin lack the capacity to address voting rights. Most are largely volunteer-run and have limited resources. While they are aware of the state’s disenfranchisement laws, Conway said, they are focused on larger issues such as reducing the nation’s prison population and restructuring sentencing laws, or more immediate concerns such as finding work and housing for people just released from prison.

“I think we kind of forget that voting is almost a vaccine to a lot of these issues,” Conway said.

Neither the Republican Party of Texas nor the Texas Democratic Party could point to specific outreach efforts this election season that targeted former felons. Tariq Thowfeek, the communications director for the Texas Democratic Party, said such efforts are coordinated at the county level.

Bill Kleiber, executive director of the Restorative Justice Ministries Network, and his team of volunteers are some of the few people in the state dedicated to registering felons, no matter whether it’s an election year.

Kleiber has gone to the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville every weekday for over a decade to meet prisoners who are being discharged. He helps those who are eligible fill out voter registration forms, which he mails to county voter registration offices across the state.

“We want to fully engage them as part of our society and give them a voice. If you don’t have the right to vote, then you don’t have a voice,” he said.

That sentiment is shared by Rep. Harold Dutton Jr. (D–Houston). “If it didn’t matter, we wouldn’t have taken it away” was the slogan for a voter registration drives he organized for former felons in Harris County.

“If we could get ex-offenders to vote, then we could revolutionize the system,” he said. A 2013 report from the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition found that more than 27,000 adults in Harris County had felony charges.

Dutton authored a 1997 law that eliminated a two-year waiting period for felons before they could vote after they fulfilled parole and/or probation. In 2005, TDCJ started providing a “Notice to Offenders” upon discharge from prison that states that “you’ll regain voting rights in Texas beginning with the actual date you fully discharge all sentences,” along with a voter registration application.

In 2007, Dutton co-authored a bill that would have required the TDCJ to notify offenders who have completed parole or probation that they are eligible to vote and provide a registration card. Gov. Rick Perry vetoed Dutton’s bill, saying he did not believe registering former offenders was part of TDCJ’s “mission.”

“I find it unseemly that the state would make a greater effort to register former inmates to vote than we would any other group of citizens in this state,” he wrote in his veto message, adding that “when an individual is released from prison and their rights are restored, it is imperative that they take personal responsibility for all aspects of their life, including their right to vote.”

Dutton said TDCJ’s current policy isn’t sufficient because far too many former offenders don’t realize that they can vote. He plans to introduce a bill in the 2017 legislative session that would allow felons to regain their right to vote after they complete their prison sentence and parole period but while still on probation. Four states have similar laws.

“If a person has committed a crime and that person is on probation, that means we’re trying to get that person back into our life, so I think they ought to regain their right to vote when they’re on probation,” Dutton said.

The right to vote is a simple, yet effective way to get formerly incarcerated people involved in their communities, said Tomas Lopez of the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute affiliated with New York University School of Law that seeks to improve the nation’s democratic and justice systems. He said that there is no evidence that withholding the right to vote deters crime.

Disenfranchisement affects African Americans and Latinos disproportionately because disparities exist in the criminal justice system, Lopez said. In Texas, 6.2 percent of African Americans are disenfranchised, according to The Sentencing Project, which found that 23 states disenfranchise more than 5 percent of their African American adult citizens. African American disenfranchisement rates exceed 20 percent of the adult voting age population in Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia.

Had Conway been able to vote immediately after he was released from prison into the Austin community on parole in August 2000, a more progressive version of Dutton’s proposed legislation, he would have been able to vote in the previous four presidential elections.

“Until you’re actively involved in the political process, you don’t appreciate the power of voting,” Conway said. “After becoming an organizer, I realize the power of a concerted effort.”

Reporting Texas is participating in Electionland, a ProPublica project that will cover access to the ballot and problems that prevent people from exercising their right to vote during the 2016 election.