As Pay and Prestige Grow, More Men Pursue Nursing

By Estefania Espinosa

Reporting Texas

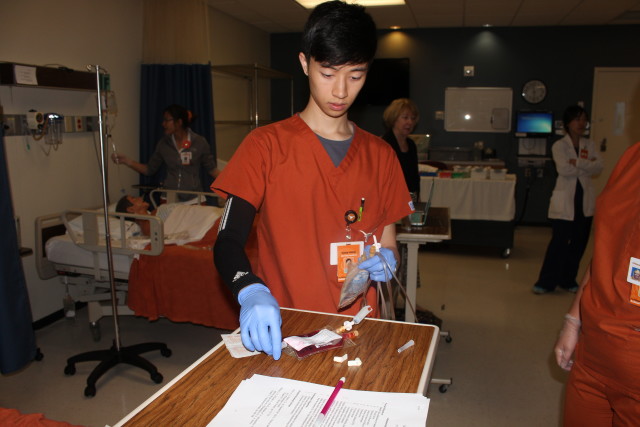

Casey Luong, third-year nursing student, examines his materials for an exercise in his Clinical Nursing Skills II class at the UT School of Nursing in Austin, TX., on Wednesday, March 30, 2016. Estefania Espinosa/Reporting Texas

Casey Luong enters a classroom that simulates a hospital: Medical dummy patients lie in beds. From a clear plastic bag, he takes out a bundle of clear tubing, a bag of saline solution and another filled with fake blood. He wears burnt orange scrubs, a plastic badge that reads “Nursing student” and blue latex gloves. Carefully, Luong begins to connect the tubes to the bags. Once the fluids are ready to be administered, he hangs the bags from a metal infusion pole next to his inanimate patient.

The exercise is part of his clinical nursing skills class at the University of Texas at Austin. Luong, 21, from Sugar Land, is a third-year nursing student, one of only six males in a cohort of 60. When he graduates next year, he will join a small but steadily growing fraternity of male nurses across the country. Experts say more men are gravitating to nursing as wages rise, particularly in certain specialties, and social respect grows.

“At one time, nursing salaries were thought of as a family’s second income, but now it’s a career where someone, male or female, can support a family,” said Carole Stacy, a Lansing, Mich.-based consultant for the National Forum of State Nursing Workforce Centers. The forum works to increase the supply of nurses to address a shortage nationally. Stacy has been involved in programs that allow professionals in related fields, such as paramedics, to become registered nurses in one year — a move, she said, that has contributed to the growing number of male nurses.

“I keep saying we really have moved the needle in our numbers of men in nursing,” Stacy said in an interview.

The nationwide proportion of male registered nurses was 9.6 percent in 2011, an increase of 2 percentage points over 2000, according to a report issued in 2013 by the U.S. Census Bureau.

And the increase is true not only at the rank of registered nurse, which requires a four-year college degree, but also – more gradually – at the ranks of licensed practical nurses and licensed vocational nurses. Those jobs typically require one year of training, and those nurses work under the supervision of registered nurses. In 2011, 8.1 percent of licensed practical nurses were male, compared to 7.6 percent in 2000, according to the same Census Bureau study.

In Texas, male nurses make up 11.4 percent of all nurses, according to a 2014 report by the Texas Board of Nursing.

Luong said he was drawn to the field by the nurse-to-patient interactions.

“You feel like you’re doing something for somebody else,” Luong said. “Your job is to take care of other people and to make sure that their health is well.

“Fulfilling would be the best word for it,” he said.

Nursing experts say male nurses are most often seen in intensive care units, emergency departments and operating rooms. The proportion of men was highest for the best-paid nursing occupation, nurse anesthetist, at 41 percent, according to the Census Bureau study. But in other areas, such as maternity wards, male nurses are rarer.

Miguel Laxa, 26, who works as a clinical nurse in the post anesthesia care unit at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said he is often mistaken for a doctor.

“It’s a stereotype we haven’t quite grown out of yet,” Laxa said. “We get patients who are older and still think, ‘Boys are doctors, and girls are nurses.’ ”

Danica Fulbright Sumpter, assistant professor of clinical nursing at UT, said she has seen changes in expectations of gender roles in nursing — including, once, at a middle school for Career Day.

“Some of them did chime in that not only girls can be nurses,” Sumpter said.

However, Sumpter has also found herself mistaken for a student. She works in a program for students pursuing nursing as a second career; a doctor once congratulated one of her students, an older white man, thinking he was the instructor.

“It could be age, it could be race, it could be gender,” Sumpter said of the doctor’s assumption that the male student was the teacher. Sumpter is 39 years old and African-American. “It could be any number of things.”

Laxa, who has wanted to be a nurse since he was in high school, said he has been encouraged to become a physician.

“Earlier in my career, people would say, ‘You’re so smart. Why wouldn’t you just become a doctor?’ ” Laxa said. “I respect doctors and the work they do, but I’ve never felt that it was my calling to become a physician.”

Male nurses may make special contributions. For instance, Laxa said, his female coworkers ask him to help them turn over a patient or perform other tasks that require heavy lifting, but he doesn’t view this as discrimination because strength is a positive quality.

“Discrimination is for a weakness,” Laxa said. “They assume I’m strong, which is a good thing.”

Laxa said the closest thing to discrimination he’s faced has been when devout Muslim women have requested a female nurse.

Sumpter said in the past, her male students, especially if they were physically attractive, received preferential treatment from the female nurses in the hospital. She said it happens less frequently now that the number of male nursing students is increasing.

“I don’t know if it’s one of those things where it’s a rarity, like, ‘We have a boy here today,’ ” Sumpter said.

Male nurses make $5,100 more annually on average than female nurses, according to the 2013 Census Bureau report. Author Liana Christin Landivar, a sociologist, said the wage differential may be partly explained by men taking jobs in higher-paying specialties, but not entirely.

“Known as the ‘glass escalator’ effect, men have typically enjoyed higher wages and faster promotions in female‐dominated occupations,” the report said. “As men entered nursing in greater numbers, they were more likely to become nurse anesthetists, the highest paid nursing occupation, and least likely to become licensed practical or licensed vocational nurses, the lowest paid nursing occupation. Even among men and women in the same nursing occupations, men outearn women.”

Sumpter, the nursing professor, said she thinks the gap will widen as more men enter the field.

“We, as women, [have to] mobilize and speak up and say, ‘This is not right. We need equity in pay,’ especially since, you know, we were here first,” Sumpter said.

Lynn Rew, professor in parent-child nursing at UT, said she thinks men are choosing to pursue nursing because of job stability and diverse career options. Although the name of the profession, “nursing,” refers to a female ability, such as “nursing an infant,” men are equally qualified to work in this field, Rew said.

“Males are capable of the same kinds of feelings as females and are generally not afraid to let other people see this softer side of themselves, the feminine side,” Rew said.

Rew said there are more important considerations than gender.

“When people are really ill, it doesn’t seem to matter what the gender of the nurse or physician is,” Rew said. “The important thing is that they know what they are doing and why, and that they care and provide that care with respect for the dignity of the patient.”