UT Researchers Use Laser Light to Fight Depression, Anxiety

By Kate Thackrey

Reporting Texas

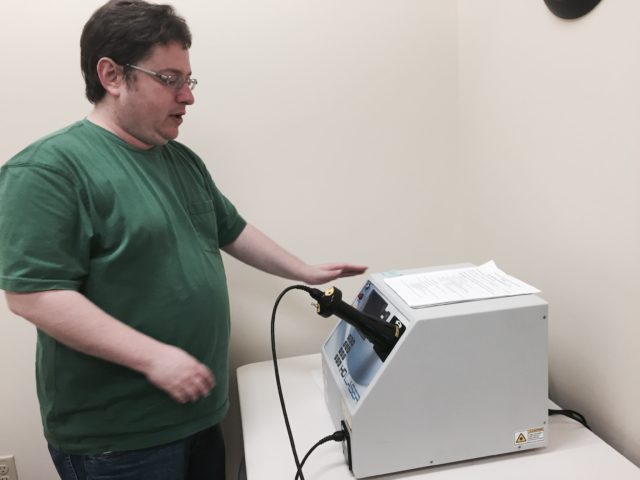

Lab manager Douglass Barrett with an infrared laser UT researchers are using to treat depression and anxiety. Kate Thackrey/Reporting Texas

For Reporting Texas

Francisco Gonzalez-Lima and his colleagues at the University of Texas at Austin are testing the use of lasers to treat people with anxiety, depression and even mental decline.

Held against the forehead, his group uses a laser to energize parts of the brain that control decision-making and higher brain function, all at one-twentieth the power of a 60-watt light bulb.

Gonzalez-Lima said the laser energy gives the prefrontal cortex more to work with when a patient is trying to complete therapy, making them more receptive to learning.

“Any function that the nerve cells are doing, they can do better, because they have more resources,” Gonzalez-Lima said. “It’s entirely noninvasive, it’s entirely safe, there are no side effects.”

Gonzalez-Lima came to the UT psychology department 26 years ago, when the neuroscience program was in its infancy. He taught one of the first undergraduate classes in the subject, called “behavioral neuroscience.”

He said he learned of the potential benefits of lasers in 2008, when one of his graduate students was shining light into the eyes of mice.

The student wanted to see whether the laser would prevent the eye’s cells from dying of toxins – which it did – but he wasn’t prepared to see increased activity in the prefrontal cortex, Gonzalez-Lima said.

“We did it first in the eye,” Gonzalez-Lima said, “because we didn’t know it was going to go through and do anything to the brain.”

Today the lab focuses on one enzyme, a molecular mechanism found in all cells called cytochrome oxidase that consumes oxygen to produce energy.

Think of oxygen as fuel for the cell: The more you convert, the more energy the cell can access. cytochrome oxidase is the bottleneck for burning that fuel, controlling how much oxygen is used.

Gonzalez-Lima said he found a way to hijack the system by shining the right type of light at the enzyme.

The light, which uses an infrared frequency too dim for the human eye to see, boosts cytochrome oxidase activity, taking in more oxygen and building up energy reserves for neurons to use.

“Essentially, you’re transforming the energy of light, photons, into chemical energy,” Gonzalez-Lima said. “It’s a completely different idea from the way that drugs operate … much easier and cheaper and safer.”

Patients undergoing treatment for mood disorders can use the lasers to solidify the things they’ve been learning, Lab Manager Douglas Barrett said.

Barrett said that for a critical period of four to six hours after treatment for ailments like anxiety, cognitive decline and depression, memories are vulnerable to manipulation.

In preliminary results for studies with anxiety and memory, subjects given the laser treatment for eight minutes showed significant improvements over peers who completed traditional treatments, he said.

“It’s not like people walk out of here like supermen,” Barrett said. “But it will be another tool in the arsenal: some combination of low level light therapy and drug therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. If you approach from all these angles, it’s got a lot of potential.”

The laser doesn’t work on normal subjects beyond minor improvements in memory, Barrett said.

For his newest study, Gonzalez-Lima is partnering with Christopher Beevers, director of the UT Institute of Mental Health, to see whether using the laser method can make depressed subjects more receptive to online therapy.

The study is one of several by Beevers, who is testing patient reactions to an online depression program called Deprexis. The program uses principles of traditional cognitive behavioral therapy: It focuses on recognizing and breaking negative habits and thought patterns.

“Depression is kind of the common cold of mental health conditions. Most of the treatments we have are modestly effective,” Beevers said. “What we’re trying to do is use those basic discoveries to inform the development of new treatments.”

The study is unfunded, but if the therapy pans out, Beevers said, he’ll seek funding for more in-depth research.

Some researchers have even started classifying the laser method as its own field, called photomedicine.

In 2004, the Massachusetts General Hospital created the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, one of the first research centers dedicated to light therapy, which later formed a research partnership with Harvard.

Infrared lasers have been approved for physical therapy by the FDA, classified under the same category as heat lamps.

Gonzalez-Lima said that although dentists and veterinarians are starting to use lasers, in his experience medical professionals lag behind in applying laser therapy.

“This has not reached modern medicine,” Gonzalez-Lima said. “At UT, we need a center for photomedicine to be competitive.”

Enrique Vargas, a neuroscience and biochemistry sophomore at UT, said that working in the Gonzalez-Lima lab has helped him expand his research skills.

“Almost everything you do here is new – there’s no template you follow. That really allows us to be creative in our decisions,” Vargas said. “Photomedicine can be applied to anything if you put your mind to it.”