In Numbers and Culture, Policewomen are Outsiders

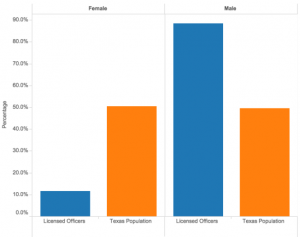

Women outnumber men in Texas, but they make up only 11.5 percent of licensed peace officers.

As bars close, a mounted policewoman directs the crowds away from Sixth Street in Austin. Photo by Rocio Tueme/Reporting Texas

By Reporting Texas and The Dallas Morning News

This story was written by Caroline Covington and Rachel Phua, based on reporting by Covington, Phua, Fauzeya Rahman and Teresa Mioli.

When Margo Frasier was a captain with the Travis County’s Sheriff’s Office, she made maternity uniforms available to her female deputies. That was in 1981. A maternity uniform may seem like a small thing, but it at least acknowledged there were women in a field dominated by men.

Frasier, who became Travis County’s first female sheriff in 1997, now serves as police monitor for the Austin Police Department. About one in 10 of the department’s officers is a woman.

Women still have a long way to go, she said.

“Sadly, the numbers haven’t changed very much,” Frasier said. The statistics, she said, “reflect a lack of effort.”

Austin Police Monitor Margo Frasier, formerly the Travis County sheriff,

attends a citizen review panel at City Hall. Photo by Rocio Tueme.

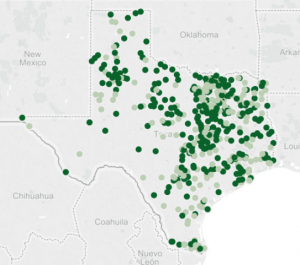

A Reporting Texas analysis found that as of early February, about 11.5 percent of the licensed peace officers in Texas were women. More than half of the state’s population is female.

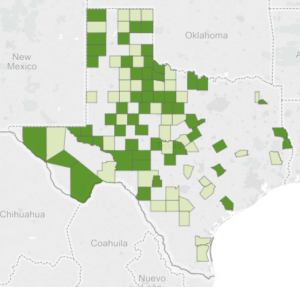

Almost a third of all police departments in Texas have no female officers. More than half have no more than one. There are no female sheriff’s deputies in 54 of 254 counties, and 43 counties have no more than one.

Experts say many law enforcement agencies don’t make a strong effort to recruit women. Women who get hired can face discrimination, limited opportunities for promotion and sexual harassment. Physical fitness standards designed for men may also make it hard for them to qualify.

“The problem is, discrimination is very hard to prove. Unless you have a tape recorder in your pocket, you’re not going to get much evidence,” said Barbara O’Connor, president of the National Association of Women Law Enforcement Executives.

Coveted jobs

State agencies offer some of the more coveted and higher-paying jobs in Texas law enforcement. Most are overwhelmingly male.

The Texas Department of Public Safety employs more than 4,700 licensed peace officers, the most of any law enforcement agency in the state.

The Reporting Texas analysis, based on what DPS reported to the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement, found that slightly more than 5 percent are women. DPS spokesman Tom Vinger disputed that number, saying “just over 6 percent” of the agency’s “commissioned personnel” are women.

The analysis focused on licensed peace officers, the men and women who enforce the law throughout the state. Vinger said women make up nearly 43 percent of the total workforce at DPS.

He said the percentage of women at DPS is comparable to that of state police elsewhere in the United States and that his department puts a premium on diversity.

A 2010 U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics report, based on 2007 data, estimated that nationally, 6.5 percent of the officers working for statewide police agencies such as the DPS are women, compared with 12 percent of the officers working for local law enforcement agencies.

In 1993, the first women joined the Texas Rangers, the state’s oldest and most prestigious law enforcement unit. The unit was originally formed in 1823, according to the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco.

Just last year, Vinger said, a female officer was promoted to lieutenant for the first time.

The Texas A&M Forest Service, an agency with roots in the Piney Woods of East Texas, currently has no women in its law enforcement division.

Les Rogers, the service’s chief law enforcement officer, said the job often requires officers to travel at a moment’s notice. And that deterred at least one promising female candidate. Rogers said she was a single mother who was unsure whether she could leave her son for extended periods of time.

The Forest Service has never employed a female officer.

About 7 percent of Texas Parks & Wildlife game wardens are women. Women are applying for warden positions, and the agency’s most recent academy class had four women out of 21 cadets, said Danny Shaw, deputy director for the agency’s law enforcement division. So far, about a tenth of applicants for the next class are women.

Shaw said women perform the job just as well as men.

“We’ve got to redouble our effort in all of those areas regarding diversity,” he said.

Recruiting women

The Paris Police Department was among those that had only one female officer, out of a total of 57 officers.

Det. Nica Blake said she hasn’t experienced discrimination since she became a Paris police officer. But she does believe gender discrimination and harassment are still issues in law enforcement.

“There are male officers who think females aren’t strong enough for the job,” Blake said.

She recalled during her training when a male supervisor “felt that [she] didn’t handle the situation properly.” She had used force on the offenders but didn’t handcuff them.

“He told me that I was too nice and naive,” Blake said.

Paris police Lt. James Womack, who is in charge of recruiting, said the department is looking for more female applicants but that it isn’t easy to attract women to a rural community. The department, however, has tried to make it easier for women to join the force, he said.

“We modified the physical examination several times. We cut out the bench press test,” Womack said.

The U.S. Justice Department filed a lawsuit in 2012 against the Corpus Christi Police Department for allegedly using its physical fitness test to eliminate female applicants. Corpus Christi was accused of using a test that “did not properly evaluate whether a candidate was in fact qualified for a police officer position,” according to a Justice Department statement.

The case was settled in 2013. Corpus Christi agreed to change its physical fitness test to comply with federal laws prohibiting discrimination. The city also agreed to offer some of the women who failed the test jobs with retroactive seniority and benefits.

Other Texas law enforcement agencies still have the same physical fitness requirements for both men and women. The Austin Police Department is one of them.

“It is fair because the female officers have to do the same as male officers,” said Gizette Gaslin, a recruiter for the department.

Pregnancy discrimination

Experts say being pregnant creates huge problems at work for female officers.

“What a lot of these agencies do is that when they find out the female is pregnant, they’ll immediately pull her off duty or give her an administrative job,” said Helen Yu, who studies the role of women in law enforcement at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi.

A federal law is designed to stop pregnancy discrimination in the workplace and both the International Association of Chiefs of Police and Women In Federal Law Enforcement have issued guidelines. But Yu said few law enforcement agencies follow them.

Garland attorney Rhonda Cates, who practices employment law, said she still sees the same kind of pregnancy discrimination cases that she saw 10 years ago.

Cates said pregnant officers have been forced to use up sick leave or unpaid time off if police departments don’t have “light duty” work for them.

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act says women can take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave during a pregnancy, or after the birth or adoption of a child. But “you could be four months pregnant and unable to wear the 45-pound gun belt — so they send you home,” Cates said.

Historically, women have had to take on a disproportionate share of the responsibility of child rearing. And that can make other career fields with better hours and resources more attractive to working mothers.

Blake said the Paris Police Department was supportive during her pregnancy. But even now, as a single parent with a 7-year-old son, she wishes for better child care policies and thinks about changing jobs to spend more time with him.

Fighting discrimination

Discrimination complaints suggest that gender inequality is a serious problem in law enforcement.

Click this image to explore sheriff’s offices in Texas

with no more than one female licensed peace officer.

Frasier, the Austin police monitor, said that she has received six discrimination complaints based on gender, age and race since she started in 2013. But she said she believes there are many more instances where a female officer may not file a formal complaint when she faces discrimination.

When Frasier became a supervisor a year after she became a deputy at the Travis County Sheriff’s Office in 1976, she said a senior officer told her, “when you figure out you can’t do it, come back and tell me.”

“Guys would stick nude photos in my locker … one time there was a photo and next to it was a condom filled with what I hoped was hand lotion,” Frasier said.

Frasier never filed a complaint because she “felt nothing would be done about it, and it would make matters worse,” she said.

Kim Lee, the McKinney Police Department’s former deputy chief over criminal investigations, recently filed a complaint with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

In an interview with Reporting Texas, Cates, who is Lee’s attorney, alleged that the department promoted “a lesser-qualified male” instead of Lee.

Cates said her client also felt the department had “a hostile environment against females.”

Since filing the original complaint, Lee has filed four or five more complaints alleging retaliation, Cates said. Cates said that Lee’s city car was taken away and she’s been reassigned to a department where rookies are usually sent.

The McKinney Police Department declined to comment on the case.

The Travis County Sheriff’s Office and Austin Police Department also have pending gender discrimination lawsuits. Both departments declined to comment.

Cates said discrimination is especially prevalent in smaller departments where there are fewer women and lesser protections such as civil service associations and unions.

Victims of sexual harassment often are “put on trial and interrogated for their complaint,” Frasier said.

Jennifer Rowe, a regional coordinator for the International Association of Women Police, said there is a lack of transparency in departments’ Internal Affairs sections and that “males may not be able to pick up on the subtext of the harassment made towards a female.”

The traditional image

The traditional image of policing is the biggest thing that keeps women away from the profession, said Mark Dantzker, a criminal justice expert at the University of Texas-Pan American.

“Macho” police officer stereotypes make it difficult for women to relate, he said.

The reality is that crime-fighting in the field is at most only about 35 percent of the job, Dantzker said.

“It isn’t about car chases and gunfights and wrestling people down and things like that,” he said. “It’s about helping people out.”