In Diverse Texas, Whites Dominate Police Ranks

A Reporting Texas investigation shows that many police and sheriff’s departments do not mirror the communities they serve.

Sgt. Paul Stephens of the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department patrols his community in April. Photos by Martin do Nascimento/Reporting Texas

By Reporting Texas and The Dallas Morning News

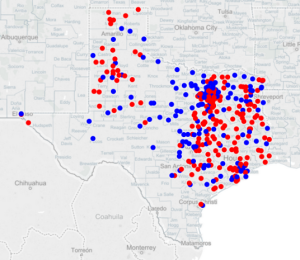

A racial divide separates many Texas law enforcement agencies from the communities they protect.

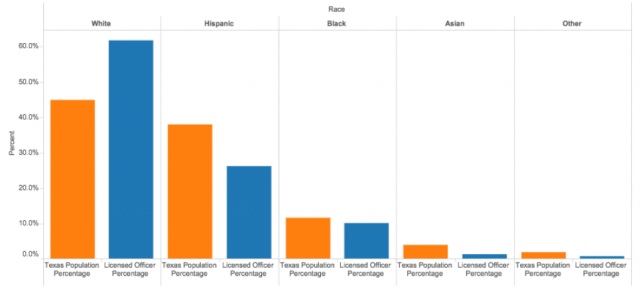

A data analysis shows that licensed peace officers in Texas, the men and women who carry badges and can make arrests, are disproportionately white. In many communities, the face of law enforcement doesn’t look much different than it did before the Civil Rights Movement.

In hundreds of cities, counties and towns across the state, white officers still dominate the ranks, even in communities where whites are the minority. In Waco, for example, almost 80 percent of the police officers are white. But whites make up just under 45 percent of the population — a gap of roughly 35 percentage points.

The analysis by University of Texas at Austin students found that almost one in seven minorities lives in a community with at least a 30-point gap between white police officers and white residents. And state records current as of February showed there were no minority officers at all in 215 police departments and sheriff’s offices.

A series of racially charged incidents involving police officers and minorities — beginning with the August death of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old black man in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Mo. — has revived debate about the racial and ethnic makeup of law enforcement agencies across the United States. At the time of the shooting, two-thirds of Ferguson’s population was black, but almost all of its police officers were white.

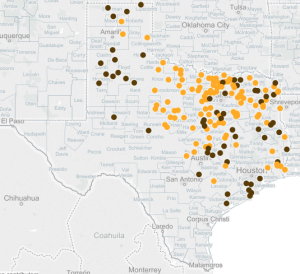

Click this image to explore the demographic divides

between Texas law enforcement agencies and their

communities.

Since then, the fatal shooting of an unarmed 50-year-old black man by a white police officer in North Charleston, S.C., and the death in Baltimore of a 25-year-old black man while in police custody have raised even more questions.

The analysis found that the majority of police officers are still white in suburbs surrounding Dallas, a ring of towns and cities that was often the first destination for “white flight” after school desegregation began in the 1970s. The majority of residents in most of those suburbs are now minorities.

“No agency wants to be the next Ferguson, Missouri,” said Phillip Lyons, executive director of the Texas Regional Center for Policing Innovation in Huntsville. “Ferguson didn’t want to be Ferguson either. But when you have an all-white police force or practically all-white police force that is policing a primarily minority community, there likely will come a day when that disparity is going to be a problem.”

There is no single explanation for the gaping demographic divides.

Minority recruiting hasn’t kept pace in many law enforcement agencies as the number of nonwhites in Texas cities and suburbs has grown, especially the Hispanic population, which has soared in recent years. Recruiting is also hampered by a strained history between minority communities and law enforcement. In some cases, little or no effort is exerted. In others, goals are set, but records are not kept to chart progress.

Civil rights advocates and criminal justice experts warn that large demographic divides between law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve can be harmful.

“If police officers are perceived as separate from the community, it could undermine crime reporting,” said Matt Simpson, a policy strategist with the ACLU of Texas. “Ultimately, this undermines the ability of law enforcement to effectively do their job. Community trust should be a cornerstone of policing.”

Gary Bledsoe, president of the Texas NAACP, said that even when officers don’t intend for it to happen, a level of fear or a “certain attitude about African-Americans” may lead to deadly police shootings or incidents of excessive force.

And minorities, he said, react to police.

“Because of things that have happened to us, we see a police car pull up or a blue uniform approach us — your heart starts pumping,” Bledsoe said. “Because you presume it’s the foe.”

Numbers that tell a story

The analysis by Reporting Texas is based on information that more than 2,500 law enforcement agencies are required to submit to the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement when they hire new peace officers. The data, produced on Feb. 3, was compared with demographic data for Texas cities and counties from the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent five-year survey.

TCOLE enforces minimum standards for licensed peace officers in Texas. But it does not have the authority to tell local law enforcement agencies who to hire, as long as the applicants qualify.

“We make sure that they are making legal hires, but we don’t have influence on who they do, or do not, hire beyond that,” said Gretchen Grigsby, TCOLE’s director of government relations.

Nor does TCOLE analyze the demographic data it collects.

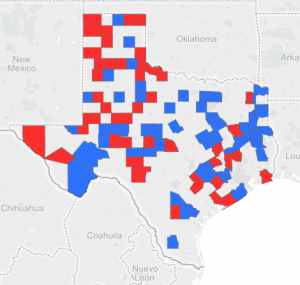

Click this image to explore demographic data for Texas law enforcement agencies and populations they serve.

John Helenberg, TCOLE’s director of agency operations, questioned whether the demographic gaps documented by the Reporting Texas analysis are enough to show that portions of the community aren’t being represented or served by their local law enforcement agencies. And any effort to reduce the demographic gaps, he said, is “completely left up to local control.”

TCOLE’s own reports show that it employed 17 licensed peace officers: 14 white men, one white woman, two Hispanic men and no blacks.

How Texas law enforcement agencies respond to the issue of diversity ranges from ignoring the problem to actively working to fix it.

Matagorda County Sheriff Frank D. Osborne said his office has a very good relationship with the minority community and an “average amount” of minority deputies. Roughly 80 percent of his deputies are white. More than half of the southeast Texas county’s residents are minorities.

Osborne said minorities mostly don’t apply for jobs with his department, but he doesn’t believe it is important that his deputies reflect the demographics of the coastal community. “We reach out to all the citizens, no matter what the race is,” he said.

“I don’t have to improve my relationship with the community,” Osborne said. “It’s already good. We have no problems here.”

Beaumont police officers Jonathan Fenner, center, and Dannie Davis,

left, work for a department in which 80 percent of the officers are white.

Other departments come close to reflecting the demographics of their communities. That’s often the case when law enforcement officers and residents are mostly of one race or ethnicity.

More than 95 percent of the police officers in Laredo are Hispanic, as are the border city’s residents. Many South Texas communities and their law enforcement agencies have similar demographics.

The same is true of predominantly wealthy, white communities: In Highland Park, about 86 percent of the police officers and 89 percent of the residents are white. Southlake in Tarrant County is almost 85 percent white — as are almost 90 percent of its officers.

Some departments achieve a near balance between the race of officers and population without giving it much thought one way or another.

Just southeast of San Antonio, the demographic profile for licensed officers in the Wilson County Sheriff’s Office is within a few percentage points of the county’s population.

Chief Deputy Johnnie Deagan said he doesn’t know whether his agency is doing anything different from other law enforcement agencies. He said Wilson County tries to hire the best applicants possible but doesn’t consider race or ethnicity.

The deputies get along well with the community, Deagan said. And his agency has never had any racial profiling complaints in the two decades he’s worked there, he said.

In some places, awareness of the need for minority recruiting efforts is spreading, but slowly.

The population of Potter County in the Texas Panhandle is more than half minority, but only one in five sworn officers in the sheriff’s department is nonwhite.

Chief Deputy David Johnson considers his deputy ranks to be pretty diverse and said he tries to “hire Hispanics to communicate with Hispanics.” About 14 percent of Potter County sheriff’s deputies and about 36 percent of the population is Hispanic.

Lt. Scott Giles, who oversees records in the sheriff’s office, said he has not noticed a disparity. He said he gets reports on the county’s demographics, “but we don’t really pay attention to them.”

“I guess we should,” he said.

Caught in a bind

Many law enforcement officials say they are caught in a bind. If they can’t recruit minorities to become law enforcement officers, they can’t narrow the diversity gap. And the tide of history has been against closing that gap.

“Police became the arm of repression after the slaves were emancipated” 150 years ago, said Bledsoe, the Texas NAACP president. The historical culture in law enforcement, he said, encouraged officers “to antagonize” and “by illicit means to try to continue to control African-Americans.”

Law enforcement was a white man’s profession well into the 20th century. It wasn’t until 1947 that Dallas hired two black men as sworn officers.

Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin, progress was slow.

The Texas Department of Public Safety appointed its first black Texas Ranger in 1988. Houston’s first black police lieutenant was appointed in 1982. Terrell Bolton became Dallas’ first black police chief in 1999.

“Even when I was a young person in my teens in the ’60s or ’70s, it was a big deal when someone had an African-American police officer hired,” Bledsoe said.

Police officer Andre Reynolds on patrol in Beaumont in April.

Starting almost from zero, law enforcement has made progress. The nation now grapples with two realities that, at first glance, seem incongruous: The United States almost certainly has more minorities and women in law enforcement than ever before. But a large demographic divide still separates many communities from their sworn officers.

Tracking progress is difficult, especially at the entry point for a career in law enforcement.

Officials at several law enforcement training academies said they don’t keep records on the race or ethnicity of who is accepted into their programs or who graduates. They say they have no idea what happens to the students after graduation.

“Because we are an open-enrollment training provider, we do not proactively ‘recruit’ students,” said Cullen Grissom, the law enforcement training director for TEEX Central Texas Police Academy in College Station. “We market our courses primarily via our agency website.”

Some police departments, such as Irving’s, hire recruits and send them to a local law enforcement academy.

Irving police spokesman James McLellan said his department is trying to become more diverse because the city’s demographics have changed dramatically.

“I think the issue you need to understand is that … people get into police work for 25, 30-plus years,” he said. “The police force we have in place right now is made up in large part of officers who have been here a long time.”

Recruitment goals have been set in an attempt to make the force more diverse, McLellan said.

“We strive to reach a 50 percent minority makeup, meaning anything nonwhite, like females and other races,” he said.

McLellan said 61 of the 78 officers hired in the past five years were either white men or white women. That’s slightly more than 70 percent of the total. But that’s just an estimate.

“Please keep in mind that we do not classify by race,” McLellan wrote. “Therefore this is my guess based on surname and skin pigmentation.”

Northwest of Houston, almost a third of the residents in Tomball are minorities. And the police force’s demographics mirror the city’s almost perfectly.

Tomball police Capt. Rickey Doerre isn’t sure why.

“I don’t really know that we do anything special,” he said. “We don’t go out and look for African-Americans, Hispanics, Indians or anything like that.”

Tomball, he said, is a “very good community that truly backs the police department.” Officers, he said, work in a department “where the lowest-level employee is valued as much as the highest-level executive.”

“As far as an officer leaving to go somewhere else, it just doesn’t happen,” Doerre said.

Latrell Shannon is a community activist who has worked with Tomball authorities for almost four decades. She attributes Tomball’s progress to a close relationship between citizens’ groups and the police department.

“Many years ago, Tomball had the reputation for being a redneck community … and I’ve seen that change,” Shannon said. “Not to say it’s still not there, but if it is, it’s very subtle.”

Racial discrimination within the police department, or by its officers, is almost unheard of, she said. And the department has “more blacks on the police force … than we’ve ever had.”

Recruiting barriers

Doerre said law enforcement agencies that don’t reflect the demographics of their communities may be having trouble attracting recruits because of their location, social or economic issues, salary, or perhaps because the agency itself doesn’t have a good reputation.

Sandra Guerra Thompson, director of the Criminal Justice Institute at the University of Houston Law Center, said if a law enforcement agency only has a “token few” minorities, that can deter others from joining.

“You have to have that certain threshold. Enough people around that others feel comfortable joining, and where the environment really does feel diverse,” she said.

Luci Saah attended college for two years in Nacogdoches before she began working on a criminal justice degree at Sam Houston State University. She said she got to know East Texas well.

“When I was there, I never saw a black officer,” said Saah, who is black. She said she would feel awkward applying for a job as a police officer in a small East Texas police department because it would be tough if she were the only woman and black.

Minority police officers continue to complain that opportunities for advancement are limited. Allegations of discrimination and racist acts within law enforcement agencies surface frequently.

Houston police Sgt. Domingo Garcia said minorities still encounter roadblocks when they try to get promoted in his department.

“It’s not that they leave their jobs, it’s that they quit trying,” said Garcia, president of the Organization of Spanish Speaking Officers in Houston.

Recent history also has shaped attitudes toward police in minority communities. The Ferguson shooting was just one incident among many in the last few decades involving accusations that police targeted minorities.

“Most African-American men are taught how to survive the police. They are taught how to avoid the police. They’re not taught and encouraged to join the police,” said Quanell X, who heads the New Black Panther Party in Houston, a controversial group that promotes black rights but has also been described as racist and anti-Semitic by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

But, he said, young black men should be encouraged to do just that.

“If you’ve been harmed by an institution, you can’t change it from the outside,” he said. “You’ve got to get on the inside and make some good changes. And you can bring your life experiences to explain to other officers why these community-police relationships must change.”

Other factors may take minorities out of the running for jobs in law enforcement.

A disproportionately high percentage of minorities, particularly young black men, end up with criminal records that could make them ineligible.

Thompson, the University of Houston law professor, said education requirements at some law enforcement agencies, such as a college degree, can be an issue for minority applicants.

“Inferior schooling” and fewer opportunities for minorities to obtain or afford a college degree result from socioeconomic disparities between racial groups, she said.

“And that can translate into a barrier … to entering a police department,” she said.

Thompson said she believed that police departments, “through lawsuits, public awareness and over time’’ will get to a point where they reflect the makeup of their communities.

“I think we will get there,” she said. “We’re moving in that direction.”

Into the future

Waco police Sgt. Sherri Kirk-Swinson said her department focuses much of its advertising resources on reaching out to minorities because it doesn’t have much of a problem attracting white applicants.

Kirk-Swinson, who works in the department’s personnel section, said about 90 percent of applicants are white. That also was the case when she first became a police officer and worked as a recruiter in 1989.

“We would love to have minorities to represent the ratio of the city, but the most important thing we want is to make sure that those are good, qualified people,” said Kirk-Swinson, who is black.

“We’re not going to lower standards just to get a certain amount of minorities,” she said. “That’s not fair for the officers who are working out there and that’s not fair to the community.”

Kirk-Swinson recognized that there are times when a minority officer may have some advantages.

“If I go to a neighborhood that is predominantly black, I might be able to understand a little bit more about the culture than somebody else who is not from the same race or the same economic level,” she said.

Lacking diversity, law enforcement agencies try to find workarounds.

All of the sworn officers in the Gilmer Police Department are white. About 40 percent of the town’s residents are minorities — and half of those are Hispanic.

Investigator Lucky Bolden said his department relies on an animal control officer, outside translation agencies and members of the public — including a worker at a Longview women’s shelter who wants to be a police officer — to communicate with anyone who only speaks Spanish.

“In the long run, the police departments all around the state have got to reflect the communities being policed,” said William Spelman, a criminal justice policy expert at the University of Texas at Austin. “You don’t have to do as much work in order to avoid friction between the police department and the community.”

The complications Texas faces in securing a law enforcement force that accurately reflects the population are spreading across the nation.

Anthony Chapa, executive director of the Hispanic American Police Command Officers Association, said many of the issues facing police in the 21st century will involve the growing Hispanic population, even in states that traditionally didn’t have large numbers of Hispanics, such as Alabama and Louisiana.

The United States is seeing “more emerging populations, and law enforcement agencies need to reflect that,” he said.

“Shame on us if we don’t,” Chapa said.