Graduation Coach Works at Front Line of School Dropout Problem

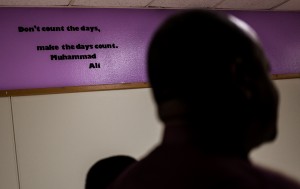

Ricardo Williams, graduation coach at LBJ Early College High School in Austin, has worked with Jose Martinez-Duran since his sophomore year. Martinez-Duran, right, is on track to graduate on time in May. Photos by Lukas Keapproth/Reporting Texas

By Gloria Fan

For Reporting Texas

Ricardo Williams doesn’t like his job title.

“Those business cards call me a dropout prevention specialist, but I don’t want to be called one,” he says. “I am a graduation coach. I don’t fight truancy. I help people graduate. I help people succeed.”

As the graduation coach at Lyndon B. Johnson Early College High School in Northeast Austin, Williams is at the front lines of keeping kids from dropping out of school. One on one, he works with students to get them back on track to graduate.

In the 2011-2012 school year, LBJ had the second-highest annual dropout rate among Austin high schools — 7.4 percent, more than double the district average. In the 2013-2014 school year, it dropped to 2.6 percent, compared with a 2.2 percent district average, according to the most recent data available from the Texas Education Agency.

When Williams came to LBJ in 2011, the four-year graduation rate was 74.4 percent. For the class of 2013, it was 85.2 percent.

Sheila Henry, LBJ’s principal, credits a mix of people and technology for reducing the dropout rate at the school, which has just under 1,000 students. The technology, called the Child Study System, is an online tool that helps schools track problem attendance and identify students at risk of dropping out. Counselors and grade-level assistant principals meet weekly to discuss students who are skipping or late to classes and ways to get them back on the road toward graduation, Henry says.

She says Williams’ dedication and mentoring are crucial elements in keeping kids in school.

Williams is one of 14 graduation coaches in Austin district’s high

schools and middle schools.

“Mr. Williams does not take shortcuts in his work. He is focused on student success and does his job with true passion,” she says.

Williams, 60, the father of seven, is a former high school math teacher, coach and software developer who ended up working in information technology in the Austin’s district’s Office of Dropout Prevention and Reduction Initiative.

The office was disbanded in 2011 because of budget cuts. Williams heard about a job opening at LBJ and applied. He is one of 14 graduation coaches in the district’s high schools and middle schools.

On a recent Friday morning, Williams leaves his office as the class-change bell rings. “I’ve got to get out and make my rounds,” he says as he starts down the school’s main hall.

Williams walks through the stream of students flowing in and out of classrooms and stops occasionally to talk. A smile never leaves his face as he shakes hands, asks students how they are doing and tells them to “keep out of trouble.”

Back in his office, Williams calls a classroom and asks to see Jose Martinez-Duran, 18, one of his star students. Two years ago, Martinez-Duran had been at risk of dropping out because he was constantly skipping school. If he didn’t start attending classes, the district could have filed a truancy case against him in court.

Williams helped him see a path to success and promised to remain by his side through every step until graduation, Martinez-Duran says.

In the time that Williams has mentored him, Martinez-Duran has matured into a successful student who will graduate in May. He has applied to a technical school and hopes to become a mechanic.

“[Williams] never quit on me,” Martinez-Duran says. “He told me, ‘It’s going to be on you, and I have faith in you.’ He did not put any guilt on me and has inspired me to become better.”

Mentoring is an important factor in increasing the chances that a student will stay in school, says Ruben Garza, a professor in the College of Education at Texas State University.

“A teacher or mentor is someone [students] see every day. … A smile or a simple asking of how a student is can go such a long way, and it’s instant gratification for the student. Students feel engaged and connected,” Garza says.

Williams uses the Child Study System to analyze every student’s attendance record. He identifies the students most at risk of dropping out and tracks them down.

“Sometimes, I got to be the bounty hunter because I have to go out and look for these students,” he says. “I begin by calling their parents, and if they don’t answer, I do home visits and find them during dinner time when everyone is usually at home. Sometimes, I will never be able to find them because they might have moved out of the state or even out of the country.”

If the search is successful, Williams brings the students into his office to talk about resuming regular attendance. “All of the students have a different story, and each of them has their own life,” he says.

Many students who drop out of high school come from single-parent families and help care for younger siblings. Some come from poor families and think it’s more important to get a job to help pay the bills, says Garza. More than 85 percent of LBJ’s students are from economically disadvantaged families and 15.4 percent are English-language learners, according to state data.

Williams, who earns an annual salary of $33,699, requires his students to sign contracts that commit them to doing whatever it takes to improve their attendance. In tougher cases, he meets with their parents and requires students to volunteer or do community service along with regularly attending classes.

Students must also turn in a form each week signed by teachers after each class they attend.

Williams’ passion for his job and commitment to helping students are clear.

“Maybe it’s because I’m a big kid. Maybe it’s because I’m a people person,” he says. “But I am definitely here to help each student succeed. Isn’t that a great thing to look forward to every day?”