‘Kissing Bugs’ on the March in Texas

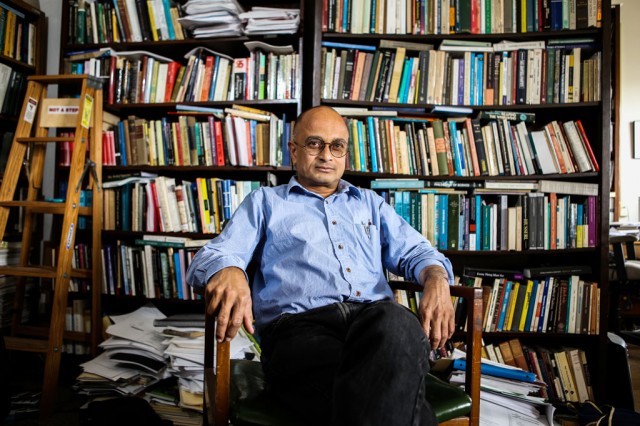

University of Texas at Austin researcher Sahotra Sarkar is tracking the spread of a potentially deadly disease called Chagas that is spread by “kissing bugs.” Photo by Megan Dolan/Reporting Texas

By Wes Martin

For Reporting Texas and The Dallas Morning News

“Kissing bugs” could inspire a horror movie.

The beetle-like insects typically crawl out of walls at night, attracted by carbon dioxide exhaled by sleeping humans.

They bite their victims on the face and lips. After gorging on blood, they defecate into the wound and transmit a parasite that causes a disease called Chagas.

Even as the media furor over the recent Ebola scare in Dallas dies down, epidemiologists in Texas face new challenges by a host of less virulent but still deadly diseases that shifting climate and population patterns are helping to spread.

Among those is Chagas, which is getting more scrutiny after it apparently claimed the life of a man in Dallas. He suffered damage to heart tissue that can develop years after a victim suffers the disease’s initial flu-like symptoms.

A total of 19 cases of Chagas were reported to the Texas Department of Health and Human Services Commission in 2013. Those are the first recorded in three decades, although health officials and researchers believe the actual number of infections is likely much higher because symptoms are often misdiagnosed or underreported.

Some researchers also worry that infections will increase because a growing number of dogs infested with kissing bugs could expose humans to the parasite.

“We’re currently monitoring the spread of Chagas,” said HHSC spokeswoman Christine Mann.

But Texas has no comprehensive action plan to stem transmission of the disease, she said.

“Part of the problem is that the state health department is underfunded and they don’t have the manpower,” said Peter Jay Hotez, the dean of Baylor University’s National School for Tropical Diseases in Houston. “They need to be given better resources. Texas and the Gulf Coast region is a high-risk region.”

So-called “neglected tropical diseases” like Chagas are particularly insidious because of their under-the-radar prevalence, said Mark Swancutt, chief of infectious diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. And, he said, public health officials not infrequently misjudge the scale of an outbreak until it becomes a crisis.

The “Kissing Bug” or Triatoma Dimidiata. Photo Courtesy of AJ Cann/Flickr

The Trypanosoma cruzi parasite can nest undetected in its human host’s heart, as well as in the esophagus or colon, and cause organs to fail years later.

Swancutt said he had no doubt that a man who suffered a fatal heart attack on his way to Dallas’ Parkland Memorial Hospital in September was a Chagas victim. He refused to identify the man, citing doctor-patient confidentiality rules.

While the recent Ebola crisis has refocused attention on the growing threat to public health from diseases that once were so rare as to be virtually unheard of in the United States, researchers in Texas raised an alarm about Chagas several years ago.

A 2010 report at the University of Texas at Austin pinpointed Chagas as a problem that “needed to be reported on, but it took a while for anything to happen,” said Sahotra Sarkar, an associate professor of integrative biology of the UT Austin and one of the researchers.

Sarkar said he and his colleagues shared the report with HHSC at the time. Since then, his team has shared more research and policy recommendations with state health officials as well.

HHSC began implementing some of those recommendations last year, Sarkar said. Tracking the spread of Chagas by making it a reportable disease was one of those recommendations.

Prior to 2013, the last recorded case of Chagas in Texas was in the early 1980s – when it was last tracked. Until Sarkar’s report, the disease had not been a particular concern to state officials.

The World Health Organization estimates that each year 50,000 people die worldwide from the complications of Chagas disease. Officials also caution that the disease can be spread blood transfusions and organ transplants.

Experts says the resurgence of Chagas in Texas — which is found throughout Latin America — is due to the increasingly adaptive character of the kissing bug.

“If you look back in the literature, it’s been here for a long time – it’s a native species,” said Edward Wozniak, the HHSC’s regional veterinarian for south central Texas. “But something has happened with it recently where people notice it more because it may’ve adapted to human habitation.”

Wozniak said he thinks that “something” is how the beetles, known to scientists as Triatominae, adapted to living in buildings and homes, especially in South Texas.

Kissing bugs are “colonizing certain types of housing,” Wozniak said. “Recently the number of sightings of them just exploded.”

The disease also is spreading because kissing bugs are infesting dogs in Texas and infecting them with the parasite. Wozniak estimates upwards of 10 percent of Texas canines currently carry the parasite.

That worries epidemiologists because even uninfected kissing bugs are at high risk of acquiring the parasite when they feed on the blood of parasite-infected dogs. Then the kissing bugs can easily jump from infected dogs to humans.

“First we heard nothing,” Wozniak said. “It really took several months – we didn’t start getting cases…until the latter part of the summer in 2013. In 2014, we’re seeing more canine cases and I’d say more human cases as well.”