Texas Women Mobilize to Continue the Momentum From the Marches

By Louise Rodriguez and Kathryn Lundstrom

Reporting Texas

Staci Lammering joined the Women’s March in downtown Austin. About 50,000 people descended on the Texas Capitol in solidarity with a movement that spurred demonstrations worldwide. Shelby Knowles/Reporting Texas

The Nomad Bar on Austin’s East Side was busier than usual for a Saturday. And it wasn’t even happy hour.

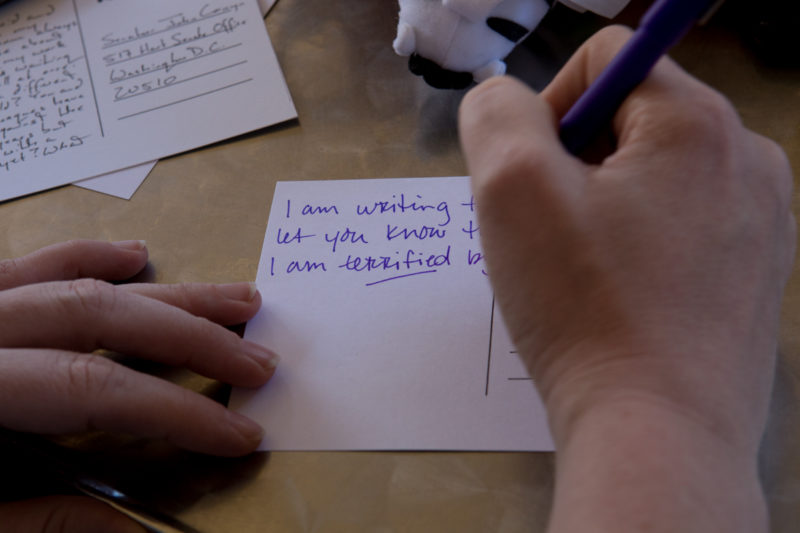

Customers at the dive bar, tucked in the heart of the Mueller-Windsor Park neighborhood, did more than belly up for another round. They also spent the afternoon writing postcards to their elected officials, opposing President Trump’s Cabinet nominees and legislation on issues such as women’s health.

On that same first Saturday of February in San Antonio, about 40 Democratic women got a crash course on how to run for political office. Annie’s List, which organized the session, said Trump’s election had triggered a surge in demand for its programs that teach women how to become candidates. One woman in attendance said the election inspired her: a week later, she filed to run for the San Antonio City Council.

“I wasn’t going to wait anymore,” she said.

Both events were among hundreds planned in Texas over the next several months aimed at continuing the momentum from the Jan. 21 women’s marches in Washington, Austin and across the country. The question remains whether the marches were simply a dramatic moment of political expression, or the beginning of a movement.

“Support quickly fades unless you keep the momentum going,” said Theresa Mullins, who teaches U.S. history at a South Austin high school and who organized the “Political Postcards and Drinking” event at Nomad.

Kathryn Gray was among about 300 people who gathered at an Austin bar to write to state legislators and members of Congress on issues of concern to them. David Lopez/Reporting Texas

A double-shot of activism

Clutching a list of addresses of Congress members in one hand and a beer in the other, participants spilled out onto the bar’s patio. Like most of the people there, Mullins, 26, is a newcomer to activism.

“You have to have people that are willing to put in the time to host an event like this, and then once the information is compiled, like, all you gotta do is go. Show up. And write what you believe in,” she said.

Randy Gregory II, 33, is a senior designer at IBM, and Anna Ruth, 29, works for a local nonprofit. They came to the bar with their corgi, Penny Lane.

Gregory said he hadn’t been politically active during the Obama administration.

“We did this to ourselves,” he said, referring to the election outcome. “Why haven’t I been doing this for years?”

Ruth said she was troubled by the lack of diversity at the national women’s march, and said she plans to attend local Black Lives Matter meetings in coming months.

“I think people will be more supportive of intersectional issues,” she said.

Cathy Hightower, 53, came with her son Matt Smith, 33, to discuss the future of health care, veterans’ issues and LGBTQ rights. Both are Navy veterans.

Smith, who is gay, expressed concern over the administration’s attitudes towards the LGBTQ community. “I was scared. But it reminded me of this John Wayne quote,” he said, reading from his phone. “’Courage is being scared to death but saddling up anyways.’”

Hightower said she has resolved to attend “Resist Trump Wednesdays” with a group of neighbors who share her concerns. “I didn’t fight for this country for a buffoon to come in and wipe out everything that we’ve done for the past 250 or 300 years.” she said.

Glenn Scott, 68, was one of the few political veterans at the bar. She was on the planning committee for the Austin Women’s March and has been active in progressive politics since she moved to Austin in 1974.

“This is not about a one-day march,” said Scott, who described herself as a socialist feminist. “We can’t fall back into silos.”

Mullins said the ability to bring together people from different backgrounds and interests is crucial to sustaining momentum from the march and healing divisions left by the presidential campaign, even among progressives.

“Sometimes I think we are so divided by our own issues or own beliefs that we are unwilling to come together,” she said.

Mullins, who provided blank postcards and some stamps that afternoon, said she and the bar plan to make the postcard-writing session a monthly event, as long as people keep coming.

By the end of the session, participants had written 1,429 postcards.

Nomad Bar donated $220, or 10 percent of the drink sales made during the postcard-writing event, to a grassroots political organization. David Lopez/Reporting Texas

No ‘good old days’ for women

A day after the Austin Women’s March, Jennifer Gamez was fed up with Trump’s claim that it was time to take the country back to the “good old days.”

“Women never had the ‘good old days,’” she said.

So Gamez decided then and there it was up to her to “be the change.”

Two weeks later, in a conference room at a San Antonio Best Western, she joined about 40 women for the $25 Annie’s List workshop. The organization has offered political training for 14 years, but the election caused interest to spike.

“People were ready to go November 9th,” said training director Kimberly Caldwell, who said calls to her office started coming in the day after the election.

The organization added events to its schedule; still, nearly all of four sessions across Texas in early February were sold out.

“We had more people sign up online in January than we did in all of 2016,” said Laurie Felker Jones, Annie’s List’s communications director.

The sessions cover the nuts and bolts of running for office: How to manage a campaign, how to develop a message and how to raise money. The women heard pep talks from mentors.

After Trump’s election, many of the women in attendance stressed a sense of urgency about increasing female representation in Texas politics.

Denise Hernndez, 26, listens to panelists at a seminar on how to run for office. Emree Weaver/Reporting Texas

San Antonio attorney Melissa Cabello Havrda, who attended an Annie’s List event a year and half ago, announced her bid for her City Council District 6 seat after the election.

“After seeing what happened, how even my children were upset — it’s time,” she said.

For Gamez, it was time to do more than support other candidates.

“I can only be on Facebook cheering on Elizabeth Warren for so long,” she said, referring to the Massachusetts Democratic senator who has been an unflinching Trump critic. “I’ve got to be Elizabeth Warren.”

Many studies show that women, unlike men, tend to be unsure about their ability to win a campaign. Women have to be reassured that they are just as qualified, said Patsy Woods Martin, executive director of Annie’s List.

Martin met “busloads” of women from all over Texas at the Austin march who were interested in Annie’s List. “There are women across the state whose attention has been gotten.”

Cabello Havrda credits the Latina Leadership Institute, a six-month program in San Antonio, for helping her to overcome self-doubt.

“At 42, I have a JD, I have an MBA and I didn’t think I had enough” to run for office, she said.

Annie’s List sessions are geared toward training women to run for local seats such as school boards and city and county offices, entry points on the track to higher offices.

In Texas, women make up roughly 20 percent of the Legislature, a proportion that has changed little since 1995. Nationwide, only one-third of city council members in the top 100 cities are female, according to the Institute for State and Local Governance at the City University of New York.

U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, an Austin Democrat, attended the San Antonio session. He said the turnout showed that the Women’s March was the start of a movement.

“If we’re ever going to change this state, it will be because there are women who take a risk to run,” he said.

Participants in the Austin Women’s March expressed opposition to President Trump’s policies. Shelby Knowles/Reporting Texas

A moment or a movement?

While the U.S. marches drew an estimated 4.2 million participants, size alone doesn’t correspond to the potential for change the way it did during the 1960s civil rights movement, said Zeynep Tufekci, who studies social movements in the digital era at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Social media makes it too easy to quickly mobilize crowds for protests.

In a recent op-ed for The New York Times, Tufekci praised the Women’s March “10 Actions in 100 Days” plan, which began with the postcard event and will include other activist events. Tufekci warned, however, that raw turnout is not enough.

“A protest does not have power just because many people get together in one place. Rather, a protest has power insofar as it signals the underlying capacity of the forces it represents,” Tufekci wrote.

“I’m not sure I buy that argument,” said Michael Young, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Austin who studies social and political movements.

“That was an unprecedented crowd,” he said. “This was grassroots, genuine expression of upset.”

At the postcard event, Lorrie Hoffman, 53, a health care employee who works with veterans, put the moment-or-movement issue this way:

“After the election, I woke up and said, ‘I’m scared.’ After [the Women’s March], I’m not scared anymore. People are going to get over that fear, and they’re going to get mad as hell.”