Is the Clock Ticking for the End of Time Changes in Texas?

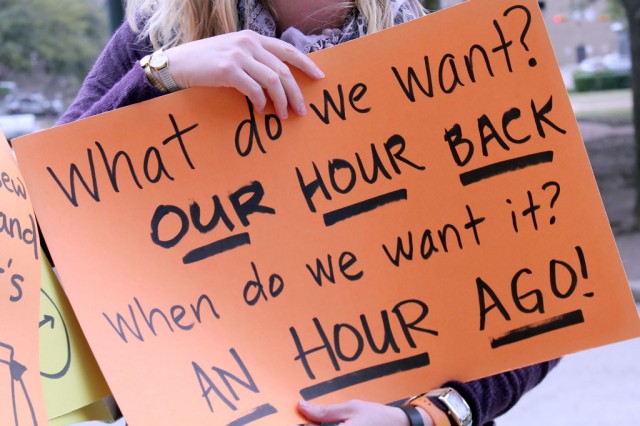

Supporters of House Bill 150, which will put Texas permanently on Central Standard Time, turned up for a public hearing at Texas State Capitol on March 11. Photo by Hannah Jane DeCiutiis/Reporting Texas

By Hannah Jane DeCiutiis

For Reporting Texas

Many Texans are tired of changing their clocks twice a year, and not just because of the hour of sleep they lose every March. As a result, two legislators have filed bills seeking to end Daylight Saving Time in the state.

House Bill 150, filed by Rep. Dan Flynn, R-Van, would put Texas permanently on Central Standard Time beginning in September. House Bill 363 by Rep. James White, R-Woodville, would form a task force to research the effects of Daylight Saving Time in Texas and recommend whether to continue the practice. Both bills got a hearing last month before the Government Transparency and Operations Committee.

Rep. Gary Elkins, the committee chair, said he believes Flynn’s bill will be voted out of committee at its April 8 meeting. “After that it will go to the Calendars Committee to be scheduled for a debate on the House floor,” said Elkins, a Houston Republican.

Once there, an academic expert on saving time predicts the bill will have a hard time overcoming the opposition of leisure, recreation and retailing interests, which support DST because it shifts some daylight to the end of the day.

Flynn said he began to survey constituents about the time change in November, when much of the nation “falls back” one hour as it reverts to standard time. Since then, Flynn said, thousands of people have contacted his office and multiple legislators have asked to be joint authors on his bill.

Kelli Linza, administrative aide in Flynn’s office, said standard time would shift an hour of daylight to the morning from March to the start of November. “Mothers are deeply concerned because they have to take their children to the bus when it’s dark,” under DST, she said.

Daylight Saving Time began in the United States in 1918 in an effort to conserve fuel for World War I, but the practice stopped less than a year later. Except for a mandatory nationwide return during World War II, the practice was observed only in some states, until Congress passed the Uniform Time Act of 1966. It required time to be standardized within time zones and imposed Daylight Saving Time from the last Sunday in April to the last Sunday in October. States could exempt themselves from DST only if the entire state did so. The states that don’t use DST are Hawaii and Arizona – excepting the Navajo nation, which observes the time change.

Daylight Saving Time has been extended several times since then; it now runs from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November.

Common wisdom holds that DST exists to give farmers an extra hour of daylight at the end of the day to work in the fields or encourages people to use less electricity in the evening.

Michael Downing, English professor at Tufts University and author of “Spring Forward: The Annual Madness of Daylight Saving Time,” said both explanations are wrong.

“It’s about shopping,” Downing said. “To this day, the biggest lobbyists for Daylight Saving Time are the leisure and recreation industries and the big-box stores.”

Extra daylight in the evening encourages consumers to shop, eat at restaurants or enjoy recreational activities. Downing said the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Convenience Stores are two of the most vocal groups that have lobbied to extend the Daylight Saving Time period.

“That’s why every 20 years we get another month of daylight saving,” Downing said. “While many bills to abolish Daylight Saving are filed in state legislatures each year – often with what seems like popular support – those bills tend to die in committee or get voted down by legislators.”

Bryan Black, communications director for the Texas Department of Agriculture, said farmers are not concerned about the potential change.

“At certain times of the year, farmers are [working] daylight to dark, so it doesn’t matter in that context,” Black said. “On a daily basis, farmers and ranchers have to be flexible, and whatever occurs in the Legislature when it comes to time, those working in agriculture will adjust to it.”

A widely cited Yale University research study challenges the argument that DST conserves energy. The 2006 study by economics professor Matthew Kotchen looked at energy use in Indiana, which didn’t observe Daylight Saving Time statewide until 2006. Until then, only 15 of the state’s 92 counties observed DST due to the fact that the state is split between the Eastern and Central time zones – a factor that also won the state a waiver from the rule that states must have uniform policies on DST.

Kotchen found that residential electricity use in the state actually increased by one percent during Daylight Saving Time. Even though people didn’t turn on the lights as often, they used heating and air conditioning much more.

Other state legislatures are considering ending time changes. New Mexico state Sen. Cliff Pirtle, R-Roswell, filed a bill this session that would put the state permanently on Daylight Saving Time, effectively putting the state on Central Standard Time instead of Mountain Time. The bill recently passed both the House and the Senate, but will face scrutiny at the federal level: states are allowed to exempt themselves from DST and stay on standard time, but they cannot opt to stay on DST permanently under the 1966 law.

“Everyone who has spoken with me has said no, we don’t like the time change, but we like the extra hour in the evening,” Pirtle said.

Martha Habluetzel, a retired veteran in Ingleside on Corpus Christi Bay, started a Facebook group in 2014 calling for either permanent Central Standard Time in Texas or year-round Daylight Saving Time. The group has since gained more than 8,000 “likes.”

Habluetzel said group members prefer standard to savings time by three to one. “I made the group for both because I figure we need to stop the changes, and we need to work together to do it,” she said.

Habluetzel organized a gathering at the Capitol on March 10 to discuss the issue with representatives, but fewer than 15 people showed up, despite hundreds of expressions of interest online.

At the public hearing March 11, Habluetzel testified for the bill.

Melissa Rowlett, a Houston resident, testified against the bill because she favors continuing to have extra daylight in the evening.

At the hearing, Elkins asked Flynn to return to the committee with a revised bill clarifying whether it would impose standard or savings time. Flynn responded that he simply wanted one time, without any time changes.

Habluetzel said she has not heard from a single person who wants the time to change twice per year. Even if the battle for a fixed time seems trivial, Habluetzel said, she will keep fighting.

“People say this is crazy, that we have more important things to fight,” Habluetzel said. “I say that’s right, but that doesn’t mean this isn’t important as well.”