Grocer’s Son, Then Doctor, Now Major Donor to UT’s New Medical School

By Qiling Wang

Photography By Qiling Wang

Reporting Texas

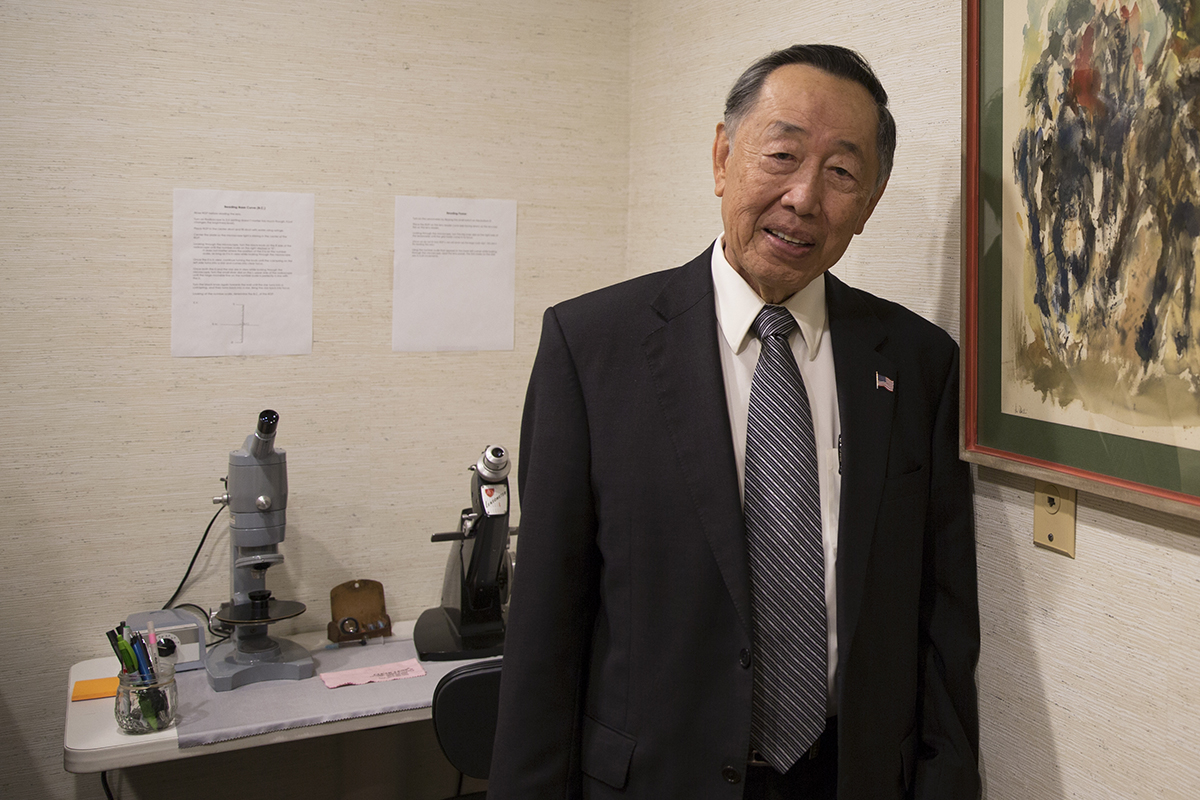

Dr. Mitchel Wong decorated his Austin office with paintings by his late mother, Rose Wong. She was an accomplished artist and a daily inspiration to him, he said. Qiling Wang/Reporting Texas

At 77, Mitchel Wong still goes to work every day at Austin Eye Clinic, the ophthalmology practice he founded in 1969. It’s headquartered in the same modest building on East 40th Street where he started his practice.

At first, he was the only doctor. The practice has grown to include his youngest son, Shannon, three other professionals and a North Austin location that opened in 2000.

He stays fit by jogging in the morning and doing yoga or Zumba after work. He only recently cut back on performing surgeries.

Aside from his professional work, he owns real estate and the Rawhide Trail Ranch in Austin, where he raises Black Angus cattle. He’s been an officer of several cattle industry associations.

Wong says he inherited his diligent spirit from his father, Fred, who worked seven days a week in the grocery business he had started in Austin. Mitchel and his sisters worked at the store after school and on weekends.

“That’s the way we grew up,” Wong said.

Due to the combination of “working steadily and making the right investments,” Wong has prospered. About a year ago, he began to think about his legacy. That led the family to approach the Dell Medical School about making a donation.

In October, the Wong family pledged to donate more than $20 million to the school to create the Mitchel and Shannon Wong Eye Institute.

“I’ve been treating eyes for over 50 years, and this seems to me a logical step,” Wong said. “With opening the ophthalmology department, we can train other doctors to do this long into the future. And it will be here long after we’re gone.”

Growing up, Mitchel Wong thought his destiny was to join the family grocery business.

It started with his grandfather, Dun Wong, who with his wife, Lee Shee, had moved from China to Mexico in the late 1800s. Dun Wong, a baker by trade, helped build Mexico’s transcontinental railroad, sending money back to his family in a village in Canton province.

The couple wanted to come to the United States after the railroad was completed. However, there had been a backlash against the influx of Chinese workers. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which blocked any more “skilled and unskilled” Chinese laborers from entering the country.

The Wongs’ opportunity came through an unusual route. In 1916, the U.S. sent troops under Gen. John J. Pershing to try to capture Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, who had been stirring up trouble along the border with Texas.

“When Gen. Pershing went down to chase Pancho Villa, [Dun Wong] baked for Gen. Pershing’s army,” Wong said.

After an unsuccessful excursion, Pershing returned to the United States and brought with him the Chinese workers he had hired, who were called “Pershing Chinese.”

Dun and Lee Shee Wong settled in San Antonio, where he opened several grocery stores.

One of the grocery stores that Mitchel Wong’s father Fred opened in the 1940s. Credit: Image AR. 2008.005(130), Wong Family Papers, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

“Our family was one of the first Chinese families with a mom and a dad to settle in Texas. There were a lot of single males that did not have their wives with them. But my grandfather had his wife,” said Wong.

Fred Wong and his siblings all were born in the U.S.

Fred Wong married another U.S.-born Chinese, Rose Chin, in 1936, and decided to follow his father’s footsteps by opening a grocery store in Corpus Christi. But they were told they were not welcome there. Instead, they moved to Austin and opened the New China Food Market at 714 Red River St. in 1938. Mitchel was born in 1939; he said he was the first Chinese baby born in Austin.

His mother chose his name but was not familiar with American spellings, so it has only one “L.”

Wong says Chinese people were still “an oddity” in the 1940s in Austin. When a childhood friend called him “Chinaman,” he reported it to his mother.

“You are not Chinaman; you are American Chinese,” she responded. If it happened again, she would call the friend’s parents, she told him.

But Wong said he did not take the name-calling personally.

“I got along well with everybody. There was no prejudice or animosity,” he said.

As his father’s grocery business prospered and expanded, Wong thought it was a given that he would become a grocer. It was not necessarily an appealing prospect: During his summers off from Travis High School, he worked up to 70 hours a week at the store.

One day, after he had worked 15 hours straight, his father suggested an alternative.

“Dad never told me to do anything, but he said, ‘You know, you can work a in grocery store, or you can try school,’ ” Wong said. “I thought for about five seconds, and I said, ‘I think I want to try school.’ ”

Wong enrolled at UT in 1957, double majoring in zoology and chemistry. He met another student, Bill Yee, who was to become his lifelong friend, at a freshman party on the first day of the semester.

“I found him to be a very good and honest person,” said Yee, a retired physicist who now lives in Florida. “We’ve been friends almost 60 years.”

Yee asked Wong to go to a meeting at the Baptist Student Union that day for the free supper. That’s where Wong met his future wife, Rose, a math and chemistry student at the University of Mary Hardin Baylor in Belton. He fell for her right away, but it took her a few years to agree to a date.

Wong graduated from UT in 1960, a year early, with honors and a degree in zoology.

Wong said his first aspiration was to become a game warden, patrolling the lakes and working in the woods, because he loves animals. He interviewed for a job but never heard back.

That pushed Wong to make another decision about his future.

Wong admired an uncle who was a family practitioner. He also appreciated the good treatment he received at a hospital after he was injured in a robbery outside the store. His conclusion: becoming a doctor would be “a good thing to do.”

He also recalled his father’s advice when he helped out at the store: “Don’t ask me what to do. Look for yourself. There is plenty to do, and then do it.”

Wong graduated from Baylor Medical School, completed his residency and opened his practice. He decorated the clinic with paintings by his mother, a gifted artist and daily inspiration to her son.

“Mom did not have high-school education. She grew up when the boys got education and the girls didn’t get that much. She’s an individual who was always thinking outside the box,” he said.

Fred and Rose Wong with their children , Mitchel and Linda, at the University of Texas at Austin

Credit: Image AR.2008.005(027), Wong Family Papers, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Both of his parents are buried at his ranch, which he bought about 40 years ago.

As Wong built his practice, he focused on the new technologies that have dramatically changed ophthalmology, such as laser surgery and advanced lens replacement techniques.

“We’ve always been looking for improvement and advances in ophthalmology….That is our philosophy,” he said.

Shannon Wong joined the practice in 1997 after interning in Santa Clara, Calif.

When he joined the practice, Shannon Wong, 48, said, “I was like a sponge, watching him as a model.” Over time, he said, he learned to build on what his father was doing and make improvements.

Shannon Wong now is in charge of most of the surgeries.

When the Wongs approached the medical school, Clay Johnston, the dean, said he assumed they meant underwriting residencies and endowed professorships, which might cost them $2 million.

But the Wongs were thinking bigger.

The school came up with a rough estimate of $20 million to create an institute.

The family did not blink, although Wong said he will have to sell some of his investments to fulfill the commitment.

Johnston was struck by their determination to support ophthalmic research – something that had not been part of the school’s master plan.

“It was incredible. I was shocked by their generosity and commitment to do this,” Johnston said. With the donation, Dell Medical will be able to focus on diseases of the eye early on and, potentially, become one of the top eye institutes, he said.