Disappearing Black Cemetery in Bastrop County Provides Link to Past

By Brandon Mulder

Reporting Texas

A toppled and unmarked gravestone in a patch of woods in Bastrop County. Michael Minasi/Reporting Texas.

About half a mile east of Texas Farm-to-Market Road 20 in rural Bastrop County, deep in a secluded thicket of cedar and yaupon trees, half a dozen eroded and toppled headstones rise out of the ground. The inscriptions on the stones have been wiped smooth by the elements. The burial ground has fallen well beyond ruin; nature has nearly erased it.

Over the years, floods have cut into the sludgy yellow soil and steadily purged the earth of the bones belonging to African-American slaves, freedmen and sharecroppers who likely toiled in the area’s fields.

The Bastrop cemetery is another instance of black grave sites being unearthed across the state as developers bulldoze land along the edges of expanding cities. The discoveries have renewed interest in Texas’ imperfect history of race relations and raised questions about how to deal with the grave sites.

In 2017, San Antonio landscape architect Everett Fly discovered 71 sets of remains that had been illegally moved by developers to a mass grave in a nearby Catholic cemetery in 1986. In June 2018, construction of a Dallas Area Rapid Transit rail line was halted after work crews discovered the grave of a 2-year-old girl while clearing right-of-way near an old black cemetery in Plano. And in April, 95 graves were uncovered in Sugar Land as the Fort Bend Independent School District began construction on a building on the former site of the Imperial State Prison Farm. The discovery has spawned controversy among city planners about how to memorialize the black men who perished in the 19th and early 20th century under the state’s convict-leasing system.

“It’s coming to light that this is a much more common issue than we thought,” said Fly, whose 36 years of landscape work has helped preserve enough black cemeteries across the nation to earn him White House recognition in 2014. For every nearly erased cemetery that is discovered and preserved — be it through painstaking research or by sheer luck — hundreds of others are lost to time, Fly said.

“It hurts my heart to guess how often these (cemeteries) are lost,” Fly said. “I would say probably thousands have been lost over the centuries — just in Texas.”

A ravine showing apparent signs of erosion near a number of unmarked graves in Bastrop County. Michael Minasi/Reporting Texas.

In 2004, the Texas Historical Commission used surveys of the 49 fastest growing counties to estimate about 50,000 cemeteries exist in the state. But only 20,000 are known. Researching, locating and preserving each one is an arduous and complex process. Deed records, census records or, if possible, oral histories are all used in locating burial sites and recovering the life stories of the deceased.

The clues researchers use to find abandoned cemeteries are harder to come by when it comes to historic black cemeteries, Fly said. For instance, black families often faced intimidation when trying to file deed records at county offices, thereby creating a gap in the chronology of land ownership.

“It’s a really massive undertaking that takes specialists in all kinds of different fields,” said Jennifer McWilliams, cemetery preservation program coordinator for the Texas Historical Commission. The process typically begins at a grassroots level before state resources come into play, McWilliams said. Landowners, descendants or county historical commissions usually launch the efforts.

In the mid-2000s, a Bastrop landowner contacted Gerron Hitem, the former state cemetery preservation coordinator, about the deteriorating burial site in Bastrop County. In 2007, Hite wrote a letter urging county officials to take action:

“The stream has apparently, over time, cut a deep ravine in the cemetery and has resulted in exposing human remains that can be observed in a steep bank of the southern portion of the cemetery,” Gerron wrote. “Obviously, this situation needs to be corrected immediately as the stream will continue to expose and wash away burials on the south end of the cemetery.”

His letters went unanswered, and the stream’s erosion has continued apace. A dozen years later, water has washed away an unknown number of graves.

But the site has found a new champion in Bastrop County Commissioner Mel Hamner, who was elected to his post in 2016. In November, after talking to U.S. Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Austin, Hamner was able to enlist help from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to address erosion issues and help save the site.

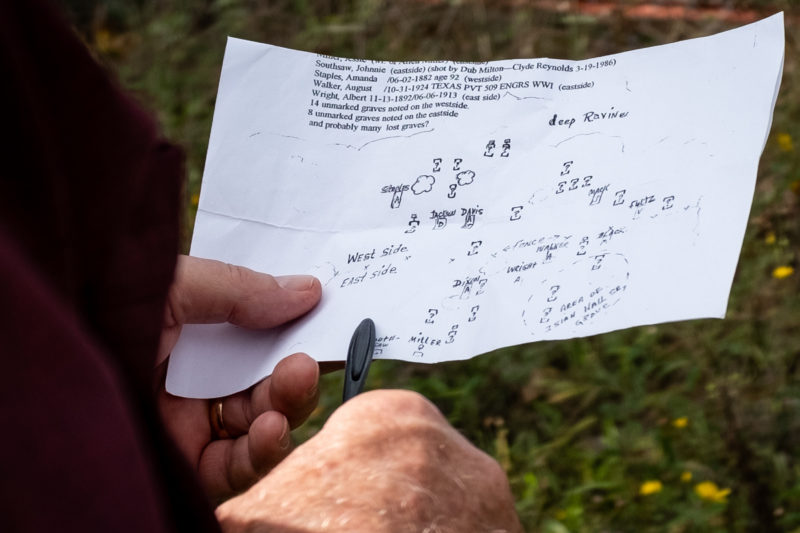

Mel Hamner, Bastrop County Precinct 1 Commissioner, points to a handwritten map of graves at Shiloh Community Cemetery while searching for lost graves on Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018, in Cedar Creek, Texas. Michael Minasi/Reporting Texas.

“Cedar Creek in Bastrop County has exceeded its banks around the … cemetery multiple times since 2007,” Hamner wrote in an October letter to the Corps. “It has unearthed many graves over this time and left the remains on top of the ground.”

Surveys of the abandoned burial site filed in Bastrop County archives show at least 34 burials “and probably many lost graves.” Most are unmarked, but records show when some of these people lived — during slavery, through emancipation and Reconstruction and into the Jim Crow era. Amanda Staples, for instance, died in 1882 at age 92; August Walker, a World War I veteran, died at an unknown age in 1924; Isiah Hall Sr. died at 94 years, also in 1924.

Their lives likely revolved around the cotton trade, said Daina Ramey Berry, professor of history and African and African diaspora studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Cotton — the driver of the Texas economy as slavery gave way to sharecropping — was booming in the region, as was the black population of Bastrop County. By 1890, African-Americans made up 43 percent of the populace, roughly double the state average, according to census data.

“These were probably relatives of those that lived there, were enslaved there, and then became sharecroppers there. They’re not memorialized, and they’re not preserved,” Berry said. “There are tons of them that are not preserved all over the state.”

Commissioner Hamner is doing all he can to prevent the disappearance of this history. He’s been coordinating with the Corps of Engineers trying to kick-start remediation, a lengthy process that involves finding funding and the completion of various studies before restoration can begin.

“We can’t let this die again,” he said, referring to the 2007 effort to preserve the site. “There might be descendants that don’t even know it’s there, and it’d be nice to resurrect it and make those family members aware—out of pure respect for the people buried there.”